By Honza Rejmanek – professional meteorologist and Cross Country columnist

Sometimes a cumulus cloud can give us insight into how the upper portion of a thermal behaves. This is because many cumulus clouds are nothing more than a thermal that has reached the condensation level.

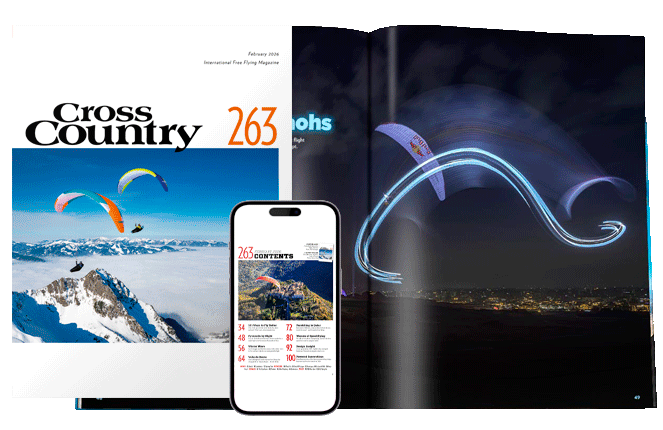

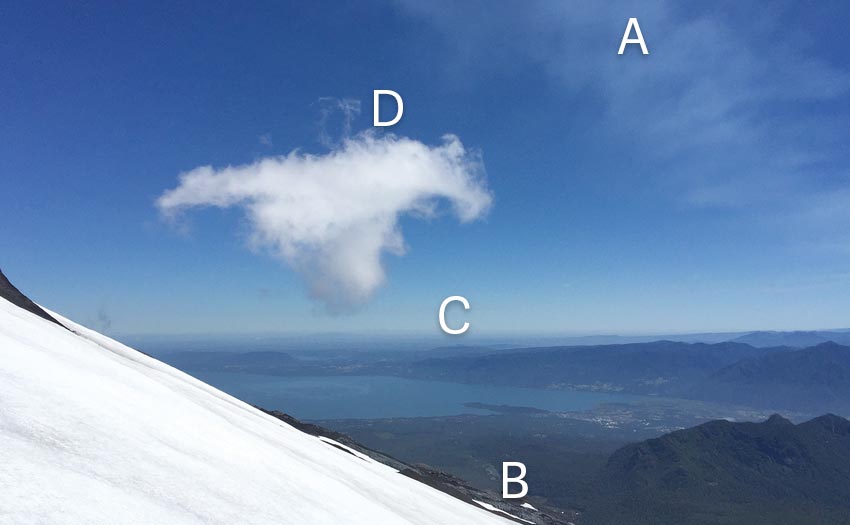

This photo was taken at noon in January on the northern slope of Volcano Villarrica (2,487m) which lies close to 40° south latitude in Chile.

It is summer in the southern hemisphere and only the upper 800m of the volcano is still covered in snow and glacier. The next 600m below the snowline is covered with granular porous black volcanic rock. Below 1,400m the skirt of the volcano widens drastically and green forests and pastures descend down to the shores of Lake Villarrica, which sits at 220m.

Photo: Honza Rejmanek

The cloud is in the lee

Above the cumulus cloud we see what looks like a diffuse contrail (A). This is actually the smoke emanating from the volcano’s crater. The gently venting smoke of this semi-active volcano acts as a massive windsock indicating south wind at crest level. This puts the small cumulus in the lee of the volcano.

The thermal for this cumulus originated on the black rocky slopes below the snowline (B). At noon in the summer these north slopes are receiving very direct heating. Granular porous black volcanic rock is a poor heat conductor and it also dries quickly. Being dark, the rock has a low albedo so less energy is reflected back to space. It can heat the overlying air very quickly, dropping the air’s density and thus creating buoyancy. This leads to the generation of thermals.

Inversion

On the distant lower horizon we can see a haze layer indicative of an inversion (C). By noon there are likely some blue thermals in the vegetated lowlands but they are not reaching condensation level due to the inversion. It is therefore fairly safe to assume that the cumulus in this photo is the top of a thermal that has originated over the volcanic rocks.

The rocks begin at an altitude that is near the top of, or slightly above, the low land inversion. However, it is not uncommon to see multiple inversions, or at least multiple stable layers, in a sounding of the troposphere. The flat shape of the cumulus top shows that it is topping out at a very stable layer or an inversion. It is being forced to spread sideways in all directions. This is also indicative of the absence of strong wind in the lee of the volcano. Above the centre of the cumulus we see a bit of wispiness (D), revealing of the remnants of the most buoyant core.

Converging air

The location and the look of this small cumulus have a lot to do with the flow dynamics around an isolated conical mountain. As mentioned the general flow is from the south. Much of the flow encountering the volcano splits on the upwind side and converges in the lee where the cumulus cloud is located. Converging air that has blown around the dark rocky part of the volcano can help feed the thermals that reach high enough to form the cumulus. Often the top of lift in a region of convergence is higher than in the surrounding vicinity. All around the volcano some thermals are likely to exist over the black rocky slopes. However many of these thermals might be fairly narrow and will mix out in the stable overlying air before reaching dew point and forming a cumulus cloud.

Sinking air

Air that has crested the volcano crater is sinking. On the snow fields from where this photo was taken the air was sinking enough to make it impossible to launch. This can be part of the reason why the cloud is spreading horizontally at its top. Not only has it reached an inversion and lost its buoyancy, it might be reaching a level of widespread sink. On this particular day it was necessary to descend down to the snowline before sinking air gave way to upslope cycles.

Lastly, the cumulus in this photo is fairly small. The amount of wispiness shows that it is in the dissipation phase. It probably no longer has a very strong thermal feeding it. In an area of convergence thermals are generally more likely to be encountered. However, thermals within a convergence can still exhibit a cyclical nature. A freshly formed cumulus with a strong thermal feeding it would not look like the cloud in this photo.

Meteorologist Honza Rejmanek has been a paraglider pilot since 1993. He has competed in five Red Bull X-Alps, and came third in 2009. He lives in California.

Get instant access to over 500 pages of Cross Country articles with our special subscription offer. We’re giving all new annual subscribers our five most recent digital issues for free. Learn to fly better with technique, weather and safety articles, read the latest glider and gear reviews, and be inspired with adventure and flying stories.