Felix Wölk stares deep into his soul as he and Michael Gebert fly the canyons and badlands of Ethiopia. All Photos: Felix Wölk

We have no idea what’s going on. We’re sitting down, trying to understand the sudden silence that surrounds us while Abenet, our friend and protector, has gone to ‘sort things out’.

Three policemen have come searching for us already. But although nobody would dare to arrest a guest at Abenet’s house – he’s an important man – he’ll need time to solve the problems that we’ve caused. We’ll be grounded for now, but at least we’re free. We don’t know what day it is, and the sun that is setting in a red ball of African glory doesn’t tell us. All we do know is it’s February and that we’re in Ethiopia.

Vague rumours about flying in Ethiopia had brought us to Degem, to the north of Ethiopia’s capital Addis Ababa. “We got mobbed, it was mental,” Bob Drury had told me about flying here, with typical British understatement.

The mountains before us had looked like free-flight pearls. Almost treeless they reached 3500 m, with take-offs in all directions. When we hiked up the conditions looked brilliant. An inversion lay over the highlands in the morning but it burnt off in strong early sun. The peaks stretched up into bright blue air, while dusty ground played host to seething thermals. Even in the early hours of our walk up dust devils crisscrossed the land and took straw and dirt high into the air.

In expectation of a great flight we hiked too fast in the thin air and overstretched ourselves, so pounding pulses and ragged breathing followed us to the summit. The wild take-off looked comfortable, but hard, strong thermals hit it from all over the place, just leaving space for a few calm seconds in between. We stole one of these moments and took off. It was strong – both up and down, but we won the game of aerial poker and came out on top, climbing hard and fast in tight circles. There was nothing smooth about it. We simply kept shooting skywards, straight to another high inversion.

Breaking through we found ourselves in bright clear air above the dust, where we climbed on with numb fingers to a freezing 4,800 m. Africa seemed to lie at our feet before we got sucked back to earth by huge sink. Then everything started: people came running from everywhere.

Some drove their herds right to the place where we were still flying, and a huge group grew like a cloud below us, mirroring our movement in the air. School was out in Degem and the weekly market just looked deserted from above. Nobody wanted to miss this spectacle.

We landed right in front of the spreading crowd, which I guessed was already at least 1,000 people, and it simply engulfed us. Everybody wanted to touch us and our amazing flying machines. When I got down on my knees I could barely see the sky anymore for it was hidden behind heads. A strong odour of burned dung filled the air and thick dust covered my throat and my tongue. Children were jumping and shouting and everybody kept moving in, crowding us. Some wanted to protect us and started randomly to hit others in the crowd with long sticks. I tried to push through the mass of people to reach the car and our mate, Federico. On the way a small child fell beneath the feet of the crowd. One man with a machine gun on his back got angry when, despite his demands, we didn’t give him our passports.

Finally reaching the car there was no way to stow the gliders, and the roof seemed to be the only way to escape the crowd, so Michael and I climbed onto it with all our gear while Federico sat in the driver’s seat behind locked doors. He tried to start the engine but it was impossible to move. The crowd started to bounce the car heavily, which made the electricity go nuts and set off the alarm system. We now had a shrill, piercing soundtrack to the mayhem.

To make matters worse there were now two heavily armed men passing themselves off as policemen. Michael was in an animated discussion with them while loading gliders quickly onto the roof. With my harness still on I tried to make space around the car, hoping to get it started.

I tried a shout, but just got met by a thousand pairs of admonishing eyes. The mood got a little tense, people grew bolder and suddenly all we could feel were grabbing hands and all we could hear was “Police station, police station”.

Finally the engine started. Federico gave an expired Portuguese residency permit to the armed men to cool them for a second, and with Michael still on the roof we did a runner. “Just get out of here!” is what we were thinking.

We reached Abenet’s place, an eco-park lodge, and, despite the roadblocks being erected to stop us getting any further, we were safe, or so we thought. Five minutes later the police arrived.

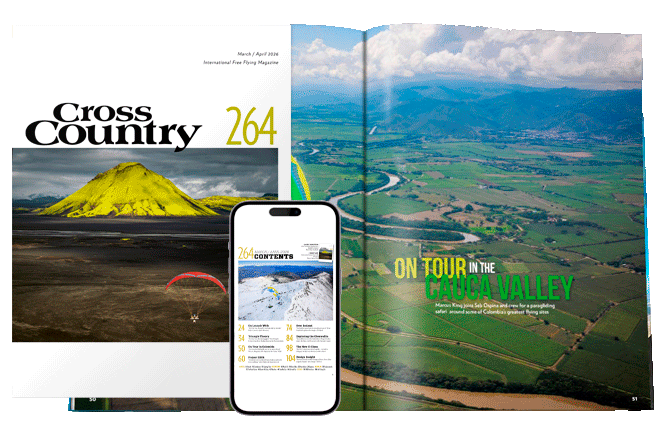

Read the rest of this article in Cross Country Issue 118, subscribe here

Issue 118 is available as a digital download here