What if someone told you that you could free-fly 200km without ever getting higher than 1,200m ASL? It would be reasonable to view them with skepticism, especially if they said you could do it while in the marine layer. Honza Rejmanek explains how it’s possible.

For most coastal regions, this would be dubious. However, in northern Chile, such flights were achieved over 20 years ago.

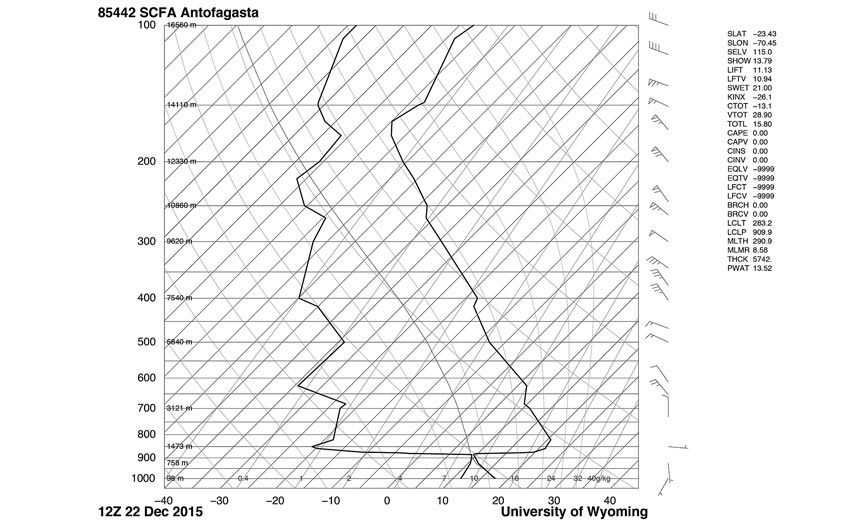

To understand how this is possible take a look at this sounding from Antofagasta, 380km south of Iquique, Chile. The terrain rises quickly on this whole stretch of Pacific coast. This blocks the marine layer from penetrating more than a few km inland.

There are other places in the world with shorter stretches of steep coastline that are capable of forming an effective barrier for the marine layer. However, what makes the north coast of Chile unique is that it does not rain there. Apart from a few cities built near rivers that originate in the high Andes, the surface is completely dry.

Northern Chile lies in the tropics, so this dry surface feels strong sun every day. There is no water to evaporate so the surface heats up fast and in turn heats the air. With cool air moving in off the ocean there is a strong contrast in the surface temperature and the air just above. This is the perfect formula for fast heat transfer to the air. This means usable thermals start forming within a few hundred metres of the coastline.

All the flying is done in the marine layer, which is capped by an extremely strong inversion. Pilots will be able to thermal up to 880mb, or about 1,000m

This sounding, taken on 22 Dec 2015, is a typical day. The marine layer is very pronounced, starting at the surface and going up to 880mb, a bit over 1,000m ASL.

The wind in this layer is light, around 5kts as seen on the wind barbs. We see that the temperature within the marine layer decreases with height at a rate that is close to the dry adiabatic lapse rate of 1°C per 100m.

The weather balloon goes up in the morning hours. However, it is common to see such a lapse rate in the marine layer even at night. The reason for this is that, out at sea, marine layers are often capped by a thin deck of stratus cloud. This is evident on the Antofagasta sounding where the temperature and the dew-point temperature are almost the same at the top of the marine layer.

The top of the marine layer is marked with an abrupt temperature increase of more than 10°C. Dew-point temperature decreases by over 30°C. The stratus clouds that mark the top of the marine layer evaporate near their tops. The evaporatively cooled air descends and causes mixing. This can be thought of as backwards thermals. It is still convection but it is driven from the top rather than the bottom.

Recently this column discussed what happens to cooling Miso soup. This backward convection can function at night. This convection is slow and would not sustain human soaring flight. Nonetheless it means surface inversions do not set up within the marine layer.

Early morning the thin stratus deck will hug terrain, but as the sun begins to heat the terrain the stratus thins out and allows more sun to heat the surface. With a heated surface, and a well-mixed marine layer moving onshore, thermals start popping. Some can be strong and tight cored.

None are strong enough to penetrate very high into the extremely strong inversion that tops the marine layer. These topped-out thermals cannot go higher nor can they move inland due to steep, high, topography. At the top of the marine layer the flow turns offshore.

On this sounding we see light SW onshore flow in the bottom of the marine layer, S flow in the middle portion and E offshore flow near the top. One can begin to visualise a helical spiral along the coastline. Abundant thermals and a northward drift allow for long flights.

Given this same sounding we can begin to imagine what flying 20km inland might be like, where the lowest terrain would be at 1,500m or higher above sea level. Above 850mb, 1,500m, we would be in effect starting to fly in a completely different layer.

It would be slightly stable in the morning but given dry air, arid surface and strong sun it wouldn’t take much past 9am for thermals to start. These would soon reach 700mb where we see a fairly deep stable layer.

Near the top of this stable layer there is a 25 kt wind from the NW. If inland the surface temperatures reached 35°C at 1,500m then even this stable layer might erode allowing for stronger winds to mix down.

Conditions inland in a tropical desert often go from turning on, to too strong quite fast. This is why in this part of the globe most pilots will choose to fly in the more tolerable conditions found within the marine layer, even though they can never thermal out of it. With 200k available, there is little need.

First published in Cross Country 174 (October 2016)