Sebastien Kayrouz hit the bullseye on 7 June 2020, flying 501km through Texas for the first 500km paraglider flight in the United States of America. By Ed Ewing

Sebastien Victor Kayrouz hit the US paragliding record out of the ballpark in June. He flew 501.6km straight distance to become the first paraglider pilot to fly 500km in the USA. Not only that, he did it on an EN-D three-liner, not a two-line racing machine, and he foot-launched from a hill rather than towed.

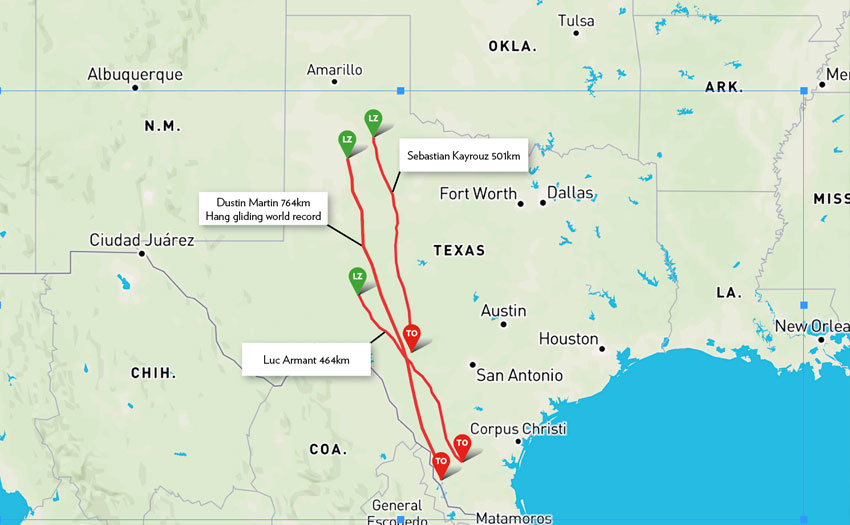

The US paragliding record does not fall lightly, and it certainly doesn’t often fall to XC pilots flying EN-D wings launching on their own from small hills in Texas. In fact it doesn’t even fall to US pilots that often. It was last broken in July 2014, when Ozone designer Luc Armant (a Frenchman) flew 463km from Hebronville, Texas; one of six 400km flights flown during an Ozone team record-hunting tow camp.

Before that it belonged to Will Gadd (a Canadian), who flew 423.4km in Texas in 2002. Our own Gavin McClurg (American) held the unofficial footlaunch record at 387km, set in 2013 from Sun Valley, Idaho.

With the record just in the bag, and with other US pilots hot-footing their way south to Texas, dragging their dropped jaws behind them, we collared Sebastien, 40, for an interview. The first paraglider pilot to fly 500km in the good ol’ United States of America.

Sebastien, congratulations. Tell us a bit about yourself.

Thank you. I’m a sales executive at Fidelity Information Services, a financial software company, and I live in Dallas, Texas. I am Lebanese by origin. I learned to fly in Lebanon in 1996.

Have you flown anything like this before?

I’ve flown some long flights before, but nothing at this scale. I held the New York state record until it was broken last week. My personal best was 232km in Oklahoma last year – it’s still the Oklahoma state record. Competitions require a lot more time than my circumstances allow me, so I focus on cross-country flying. I am also a commercial airplane pilot and a rotorcraft pilot.

Let’s talk about Texas. What was the exact final distance?

The claim for the US record will be for 501.60km straight distance and 503.53km open distance with three turnpoints.

I checked out the launch site on Google Earth, and it looks like a really obvious place to fly (from above!). What’s it like on the ground? Did you find it and develop the site yourself?

Yes, it is a location I identified but it was not the only site I had. I had three other sites I could have used but this was my favourite. I am happy things lined up and I was able to use it. It’s not a flying site, it’s just a small hill with 650ft (200m) elevation. It’s a hike-up launch and is not too challenging but it is rocky – and a nesting ground for rattlesnakes.

Was it gnarly on launch or easy?

Wind was good, 12-15mph (20-25km/h), ideal for that take-off. I didn’t have any issues. The M7 is an easy wing to launch. The only big decision moment was when to launch. I knew I only had one chance to get it right so I delayed the take-off till just about 10.45am, even though I could’ve taken off at 10.30am. I had flown there many times before and I knew where that first thermal was and I went straight there. The cycle was good and I connected quickly. I was above take-off shortly after I launched.

What’s the terrain like?

The Hill Country is challenging terrain. It is a dense forest of Juniper and Live Oak trees where thermals get triggered in the oddest of places, but they do form in almost the exact same spots.

Tell me about the weather and the forecast. I read you flew a convergence line for miles, as a storm advanced from the east. How much of that was planned, and how much chance?

Texas is at the intersection of many weather systems so conditions here are not consistent and almost no two days are alike. It is easy to get a good XC day in Texas, and maybe an extremely talented pilot can turn an XC day into a record day. However, for me to achieve a flight like this I need ideal conditions and that’s a very different ball game than an XC day.

I spent a lot of time studying and analysing the Texas weather and what it takes to have a record day. I narrowed it down to five parameters. One, convergence. Two, good wind direction and speed. Three, proper height of the boundary layer. Four, thermals, and five, clouds.

I can dive into each of them but among these factors the convergence is probably the most important, even though all these parameters are intertwined. Convergence lines in Texas are pretty common in April, May, and June. We are not talking about one, two or three occurrences per season.

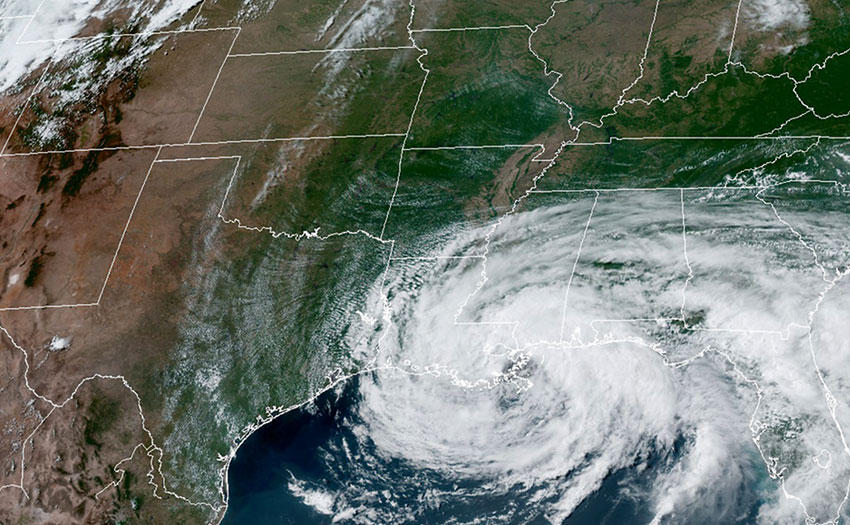

Just to give some statistics, look at the study Peterson did in 1983 and published by the American Meteorological Society*. He counted 30 convergence lines caused by drylines in the months of April, May, and June. That’s on average one convergence every three days. These convergence lines form when the flow from the Gulf of Mexico collides with dry air coming from the Pacific having travelled over hot, dry land.

Convergences can take different shapes and forms. Some are mild and make for ideal flying conditions, some are monstrous and create squall lines of thunderstorms. Not all mild convergences are favourable for flying either. The ideal convergence is a line-up leaning slightly west inside “Record Alley”. Record Alley is about 150km wide and extends over 1,200km. A mild convergence in the Alley is a jackpot.

We tend to get the mildest convergences in June and early July, and this is what makes Texas such an ideal place for long flights because it coincides with the longest days of the year when we have over 14 hours of daylight. The convergence I had was caused by a dryline and tropical storm Cristobal. I was not fixated on the record, but I knew the day was excellent and I was determined to give it my best.

You were flying the Ozone M7, three-line EN D. Good wing, but not a two-liner or comp wing. Why the M7 for such a mission?

It’s a safety consideration for me. The M7 is the wing I fly the most and I feel fully in tune with it. It’s a good wing and handled well. My harness is an Ozone Exoceat.

And instruments?

My primary instrument is a Bräuniger Galileo. I’ve had it for 18 years and I can’t fly without it. The sound of that vario is engraved in my brain. I also have a Compass C-Pilot Evo for navigation and an XC Tracer Mini III GPS as an additional track logger and acoustic back-up.

What was the wind like? Did it match the forecast?

Yes. It started average but got stronger by around 1pm, in line with the forecast. It got strong and stayed strong for the rest of the day.

Describe what the flying was like for the first 100k

The first 100km is two segments. Crossing the Hill Country and then entering the Edwards Plateau. Crossing the Hill Country is survival flying, just trying to get out of there. I kept the Nueces River within gliding distance as it is the only viable emergency landing spot. Crossing the Hill Country took about one hour 20 minutes. It is not a long distance, just above 40km, but it is challenging flying. After that I entered the Edwards Plateau. At that time I was still flying conservatively and trying to stay as high as I could.

And from 100-200km…

The 100km mark is just about Interstate 10. That’s really when the day started. That was a little after 1pm. The highway itself triggered one of the best thermals of the day and from that point on it was all about flying as fast and as efficiently as I could.

When did it really turn on and get good? How fast were you able to fly?

Just about when I hit Highway 10, the wind picked up right about that time and I started moving

pretty fast. I was hitting the 70km/h and later the 80s km/h on full bar.

Were you going to base, or just flying fast in the best part of the climbs?

In the first 100km I took the climbs as high as I could, but after 100km I never went to base. In the evening though I went back to taking every thermal as high as I could.

Describe the last 100k

Those were the last two hours of the flight and the most intense part of it. The day was still on and that’s the time of day the convergence really helps. I was getting a lot of help from turkey vultures. There were so many of them all along the way and far more than I’ve seen before. I guess they hunt for convergence lines too.

I started to get tired and I was rationing water because I ran low. I had used far too much water early on because I wanted to stay fresh and focused. I was taking every thermal as high as I could but still flying at least the McCready speed on transitions, but mostly faster.

And the moment you got 500k. It must have been touch and go… did you know you had it?

I knew I had it because I was still pretty high. I could’ve gone a little further, at least four or five kilometres more, but the terrain ahead was getting rugged and those two fields where I landed were my last chance before I reached that area. I decided to end the flight right after I hit 500k.

Your flight seems to have broadly followed the general direction of roads, which is always good. Were there parts of this flight that were way off in the boonies, or wilderness?

To be honest my focus was more in the air than on the ground to maintain the line and move from one cloud to another. For the most part the convergence line is marked by clouds stopping sharply, so you get a visual indication – although that’s not always the case.

There are a lot of roads in Texas, but many are private roads behind locked gates. There are also many country roads and farm-to-market roads, and those are public although many are dirt roads. It is not possible to distinguish them by looking down, but the trick is, if the road shows on the maps, it is a public road. I would glimpse at the map to see where the public roads are and stay aware of my surroundings, but this is not really something I actively worry about because there is always a public road close enough.

The worst I have had to do on previous flights was an hour’s walk and that was my fault. It is really not an issue if you stay aware of your surroundings and position yourself as close as possible to a public road when you get pretty low.

How was the landing?

The wind was strong and as I mentioned I was coming up to rugged terrain so I decided to end my flight. For a moment I considered a tree landing to avoid getting dragged but every patch of trees was near a house and I was worried about power lines. I finally decided to put it down in the field where I landed.

And the retrieve?

Gabbie was about 30-40 minutes behind. By the time I packed up and walked to the road she was almost there.

And the reception from other pilots, particularly in the US, when they heard the 500k mark had been broken?

I think it has really motivated a lot of people to attempt it. Soon after my flight I heard of many pilots lining up plans to go to Texas, and that makes me happy.

Are you still out there now hunting distance? What is your ultimate mission in paragliding in the US, and the world?

Distance hunting in the Texas flatlands is now an even bigger passion of mine. I developed a strategy and a system that allowed me to do this flight. This system needs a lot of work and fine-tuning and I learned a lot from this flight in particular, so that’s what I plan on doing.

From a numbers perspective, 600km [and the world record] is 20% more than this flight, but that 20% is going to take as much work as the entire 80%, if not more. I will for sure work very hard for it and give it a shot in the future.

Explore Seb’s tracklog online at XContest.

*Peterson, R. E., 1983: The West Texas Dryline: Occurrence and Behavior. Preprints, 13th Conference on Severe Local Storms, Tulsa, Okla., American Meteorological Society, Boston, J9 — J11, American Meteorological Society

‘Lone Star Cowboy’ was published in Cross Country issue 212