By Jeff Goin, author of the Powered Paragliding Bible, producer of the Master Powered Paragliding DVDs and Cross Country columnist

Always land into the wind, right?

Of course. You’ve heard that a hundred times, and indeed it’s great advice. Touching down into wind reduces risk in proportion to wind speed – a big deal.

But it’s not the only deal.

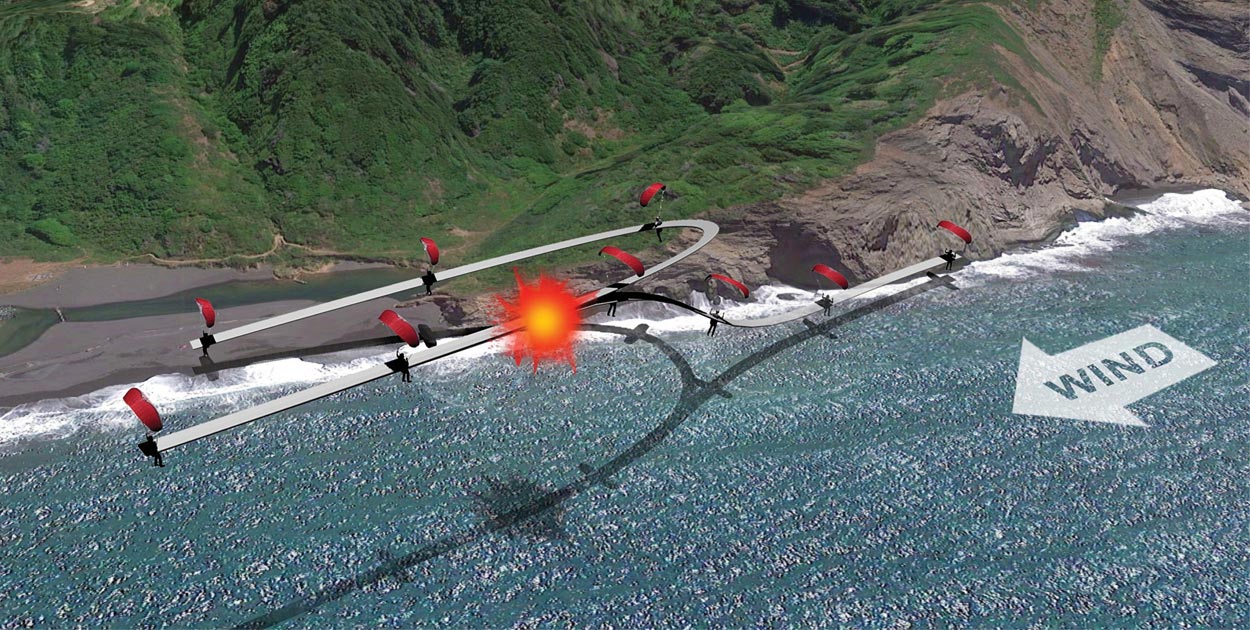

Like so many things, blind adherence to policy is not always the best policy, and we’ll show how that applies here. Look at the coastal flight illustration. It paints one of several situations where landing downwind, even when the wind is strong, can be the better alternative to landing upwind.

In this case it’s pretty clear: landing downwind on a sandy beach will be much safer than landing upwind on wave-thrashed rocks. The upwind touchdown will be fine but, flotation or not, getting thrashed about in the waves on boulders with a paramotor on your back won’t go well.

Give yourself height

Of course a much better plan is to stay high enough so this choice is unnecessary – maintaining the ability to land upwind on sane terrain. Leaving such marginal options though is inviting some pretty bad outcomes if your motor quits. Twenty metres higher and our coastal hero could have turned into-wind for a normal landing on that sandy beach. Yes, sliding in softly at 45km/h is better than being bloodied by boulders after touchdown, but landing at 5km/h into-wind on sand is even better. Height gives you time and space so you can avoid tough choices.

Flare, flare, flare

What if you are too low to finish a turn into the wind? Depending on your wing and reaction time, this will be the case when flying downwind at an altitude below about 20m, higher for smaller, faster wings.

The last thing pilots sometimes miss while trying to get into the wind at all costs is to flare the glider. If you don’t flare then you will suffer a landing that is both fast and hard.

About that flare. Unless you’re swooping, the point of a landing flare is to arrive at touchdown with minimal speed and descent rate. We assume a two-step flare where you pull some pressure to start swinging forward, then a second or so later add in brake pressure as needed.

There are two situations to consider: landing on a flat, smooth surface, like the beach; and landing on a rough one like the rocks. Smoother surfaces will allow you to do a slider landing, which is probably a safer bet. Yes, you’ll be going fast, but sliding is better than ploughing. Rough surfaces require minimum speed.

Slider landing

Slider landing

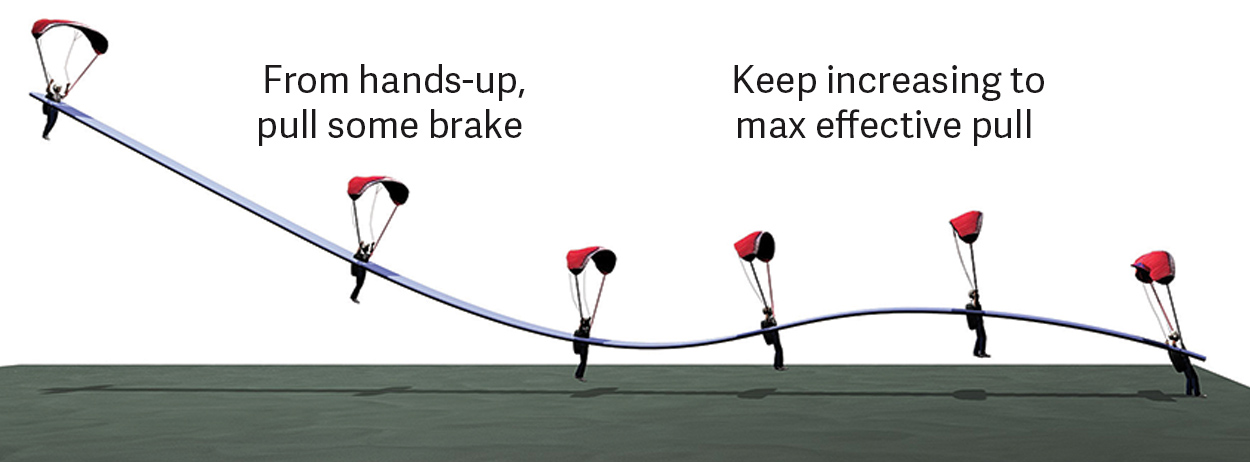

The slider landing is merely making sure that, before starting the flare, you’ve got some speed – enough to have an extended flare. Efficient wings make this easier. There are other techniques to enhance speed before starting the flare, namely diving from a strongly slowed condition, or coming out of a bank, but that’s not where we’re going. This is about simply starting the flare from a hands-up position.

Most of the approach is flown with some brakes. At just the right moment you will ease the brakes off, causing a slight dive. Speed and descent rate increase a bit. Properly planned out, the ground arrives at the natural bottom of this mild swing. Add in brake to finish it off, sliding briefly while taking on weight, and bleeding off speed.

[promobox]

One-step flare

The one-step, or minimum-speed landing also requires starting from a mostly hands-up position. The idea is to make a stronger-than-normal flare just before touchdown, climb up slightly, then keep pulling enough brake to hold the wing back until touchdown. Done properly you end up with a low descent-rate and minimal speed.

We demonstrated and filmed this technique allowing one-step landings in nil-wind, so it works, but there is a small window of entry speed and brake pull. It can go wrong in spectacular fashion. It only works if you have a slight climb of a half-metre or so. Being heavily loaded on an efficient wing may allow more climb than you want to accept; anything over about a metre of climb will result in increasingly hard landings.

Learning

If you haven’t been doing these landings, find a good instructor who can offer tips. You’re a good pilot, no doubt, but there are some things that capable instructors see that could easily save some serious drama. Like all skills, build slowly and practise in good weather, into wind, in an appropriate place.

Prerequisite skills include accurate control of the pendulum pitch swing and a solid basic flare. If landing occasionally ends with you on your bum, then continue to gain some more experience and master the basic flare before trying these two flare techniques outlined here.

‘Landing into wind’

Perhaps a better way to think of the “land into the wind” adage is to realise that it comes with implicit prerequisites: that you will first get the wing nearly level; and that you will finish a good flare before touchdown.

There are times when getting into wind, or staying in a turn may take precedence, but a good flare will always get you to the lowest possible energy state.

Practise in good conditions so you will be ready for marginal ones. The best plan is always to fly in a way that keeps into-wind landings possible on decent, reasonably unobstructed, non-turbulent surfaces. Have your landing in mind while you are flying.

Enjoy cool terrain, but if something goes amiss, and regardless of landing spot, don’t ever forget to flare.

Get instant access to over 500 pages of Cross country articles. Find out more!