How to: Fly Far

Distance is just a number - but it can be a powerful motivator too

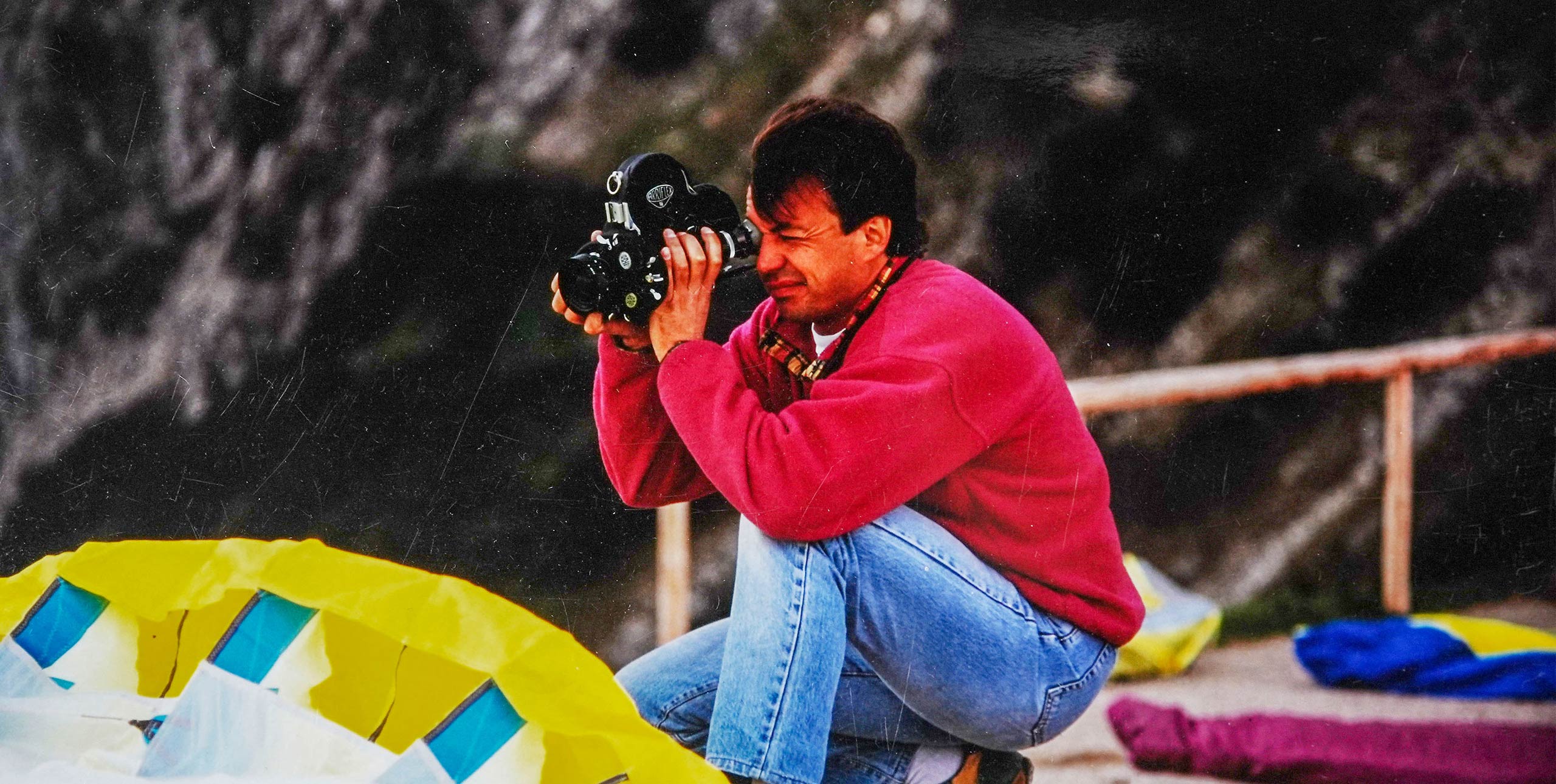

3 April, 2020, by Andy Pag | Main photo: Jérome MaupointIf you can fly 50km, you can fly 400. The difference is just a mind game,” says Alex Robé, winner of 2017’s XContest, the international online XC league. Alex has clocked up some epic distances in Brazil and routinely flies big triangles in the Alps, but is it really that easy?

Alex lives in Austria with his family and holds down a full-time job unconnected with paragliding, which means he has to be selective and disciplined about when he hits the sky.

“I’ve been flying 20 years,” he says, “but I always took my time to progress. My aim is always to fly just a bit better than last year. I never had a crash, staying on the conservative side.”

For him, there are five competences to flying cross country. “You have to be physically prepared. Have the piloting skills. Assemble the right gear, which you feel comfortable with. Understand the weather, and then there’s the mental side. That’s what I’ve focused on over the years. Oh, and there’s luck too. Luck, that’s important. Don’t rely on it, but it can help.”

The balance and importance of each of these competences has changed as he’s developed as a pilot. Before the start of this year’s Alpine season he took an hour to look back over the last 20 years to share the different breakthroughs that have helped him fly further.

Your first XCs

The success of your first flights is down to being comfortable on what you are flying, he believes. You have to feel good or you’ll never fly XC again. The metric for success is an enjoyable flight rather than the distance between take-off and landing.

“It’s all about building confidence. The core rule,” he says about inaugural XCs in the Alps, “is not too much wind. You can get nailed into a valley, and that’s not what you want if you’re beginning. It’s no fun.”

And fun, he says, builds that essential confidence. “More than 10-15km/h is too much. I use Alptherm (flug-wetter.at, licence and registration required) for predictions of lift and wind. Even days that are rated ‘Low to Average’ for paragliding are perfectly good enough for your first XC flights.

“Ideally fly in southerly winds, so you’re flying on the sunny side, with the wind helping. Don’t take off into lee. Leave that for a later stage, it’s too dangerous, and then you don’t give the passion a chance to develop.

“Choose a good site with good infrastructure and lots of good landing options.” Following a road perhaps along a valley means you aren’t worrying about how to get home and can focus on the flying.

Classic spring conditions in the Northwest Highlands of Scotland over the last weekend in April this year saw Kieran Campbell “blinking in disbelief” at the views on glide to Torridon, with views out to the Isles of Skye and Lewis. “It was certainly a step up for me,” he said. Photo: Kieran Campbell

Flying 50km

Getting to 50km is the time for developing the piloting skills to use thermals. He suggests it’s a universal skill, and once you can regularly fly 50km flights you know all you need to in terms of piloting for XC; to progress further you need to shift your focus onto the other skill sets.

One practical tip he recommends is to get to the hill earlier. “There are three phases to the day. In the morning it’s gentle, then it gets rough, and finally in the evening it becomes soft. Many pilots think, ‘I can’t fly further because the thermals get too rough’. So they should take off earlier.

“Slip into the day, get comfortable, and by the time it gets rough you’ve already got some distance and you’re feeling at home in your harness. Taking off earlier means you’ll fly for longer and further.”

For many pilots local competitions help them progress their skills. But that’s not Robé’s experience. However, this year he was invited to enter the Paragliding World Cup on the back of his XContest success. He’s not competed at that level before, and admits to being a little starstruck meeting the big names of racing when he made it to the Australian leg of the competition series in Bright in January. But he was unfazed in the air, scoring the highest-placed serial-class place, flying his Ozone Zeno into 14th overall.

He plans to be at the PWCA Superfinal in Turkey in September, but due to work and family commitments he can’t attend more than these two comps in the series.

100-150km

Recognising the changing phases of the day is important so you can change your flying style. ‘Shifting gear’, whether up or down, to fly faster or slower, is important if you want to fly the whole day and cover a lot of ground.

“When the thermals are more reliable and have a solid core, then go full-bar to the next,” he says. “Then at 4.30pm-5pm it gets gentle again, air is rising everywhere. You can cruise around much more, but don’t get too low. Enjoy the views, surf the sky. It’s the most rewarding time of day, so smooth, and the panorama is great.

“Fly through the rough stage. Stay focused, and remember you just have to stay in the air until 4-5pm. You’ll see pilots land because it was too rough for them, but if they stayed in the air another 30 minutes, it would have mellowed out.”

If you aren’t breaking through the 100km barrier then you might need to change your flying site.

“You have to go to the right spot, maybe a different country, or flying vacation. Of course you need to be lucky to get nice weather there. And it takes a while to adapt.

“If you’re used to English hills, then rocky alpine faces need a different style of flying. The thermals are more intense in the Alps, but the trigger points are easier to predict.”

At this stage it’s important to have the skills to assess where thermals are, reading the sun, clouds, birds movement, the ground geometry. But there’s more to this skill than finding a thermal.

“Can you see where the wind-protected side is? Perhaps you can see a great trigger, but are you aware when there might be heavy sink around it, that separates you from the nice elevator?

“With that level of knowledge you can anticipate the entry will be rough, be prepared to bank tightly, stick in the core for first 100m of climb, until it widens up and then you can drop back into cruise mode.”

At this level, an intuitive reading of the air built up over time with experience will hone your responses.

200km and above

“To fly 200km, it’s time to hook up with other people. It’s hard to do 200km when you’re at an unfamiliar site. It’s helpful to go with friends, or follow locals, but either way you have to go as a team.”

Team flying with locals not only helps you gauge if it’s too early to take off, but once you’re in the air it’s a lot easier to stay up in the gentle phase with a couple of other pilots. Flying the middle of the day will by now be familiar to you and you can take advantage of reliable thermals, fast climbs and gutsy transitions along the line.

“At the end of the day, where do late thermals kick off from? It’s not obvious. This is when research comes in. I download tracks, where others have flown, memorise where the thermals are. It’s crucial to have one last thermal at around 5pm or 5.30pm. It will give you 10-15km glide even if you don’t find anything else.”

Robé describes a lot of advance planning that goes into these flights. “We meet at 7.30am, at the foot of the mountain. Everyone’s excited. The forecasts are good. The day starts with joy. It’s really motivating to be with the right pilot friends. Going up the hill, we discuss the weather conditions, and what options we have. A nice triangle? Which way first? Which waypoint can we try to push further on, and which one is harder?

“We set one or two decision points: ‘If we don’t get there by 12.30pm we turn.’ Or, ‘If the wind is more than 20km from the north, we will change the plan.’”

He adds, “Flying partners need to be similar-minded people, with similar ability. It helps if wings are matched, but the overall package must fly similarly fast.” In the air some will go ahead and get stuck while others catch up and then the roles are reversed. “Gaggle flying moves faster and it’s safer.”

Many of Robé’s high scoring flights have been triangles, including one that surpassed 300km from his regular site of Antholz, just across the border in Italy. “It’s not more difficult to fly triangles, except when there are strong winds. It doesn’t make sense to battle headwinds. In big mountains they just push you down. The instruments help you decide in the air. Once you’ve done your first leg, you can see what your options are, and play with it.”

He explains, “If those first XC flights are about being comfortable under your wing, learning the weather then helps you fly further. All the time you are developing skills to make decisions, and identify safe flying conditions. But now, at this level, it’s the sum of those skills, knowledge, experience and your decisions, which make the difference.

“On the 300km triangle, three of the gaggle I was flying with got stuck pushing into the headwinds. They stopped, but I knew it was a local effect, so kept pushing, knowing that in 30km it would decrease. That’s when you need mental strength to battle that headwind. This is the key to flying far; the balance of skills.”

400km and beyond

A decade ago, a 200-250km triangle on a good day in the Alps would have put you in the running for winning the day on XContest. Now, unless you’re going to Brazil, South Africa, Texas or Australia to get 350km, you won’t register in the top ten.

“I wouldn’t have been able to do it [win XContest] without Quixadá,” he admits, referring to two 449km and 462km flights he clocked from the Brazilian take-off. “There are people touring the globe taking it pretty seriously now. Pilots go to Brazil regularly. They have a good ability, and do lots of miles. You can’t win the title by just flying my area, like you could four years ago.”

But it’s not enough to turn up on launch in Brazil. Robé spent the first week bombing out, before the flatland techniques kicked in.

“I watched online lectures about flying the terrain there. I knew what I had to do in theory: stay in zeros; no soaring; drift with the wind. I knew it but I couldn’t apply it. I kept bombing out. I was choosing the wrong flying areas, sticking with the hills. Forget that when the wind is blowing 40km/h. Soaring to windward is no good. You have to maintain 200m over the relief, and go to the lee sides, which aren’t dangerous there.”

“You’d never do this in Alpine flying. You’d be washed down in turbulence. But in this terrain, where it’s hot the ground is dry, it’s the only place thermals can build without being blown away. It took me a week to accept it and start using it to fly.”

The retrieve from a 250km flight takes all night and you won’t be back in time to fly the next day. “Each second day, when I flew over 400km, I was lucky the wind didn’t decrease at the end of the day. It worked out nicely.”

Finally, he comes back to the ‘sixth ingredient’ for flying really far. “For the really big ones, you need some luck. Spending 10-11 hours flying, you make so many decisions, so sometimes you need luck to make up for the bad ones.” As he said at the start, “Don’t rely on it, but it can help.”

Lex Robé, 43, has been flying since 2001 and averages “30 flights a year, half of them XC”. In 2017 his flying highlights included flying a 307km FAI triangle in the Alps, setting a new site record for Grente in the process, and two big flights in Brazil: 462km and 449km from Quixadá on 1 and 3 November. A mechanical engineer he lives in Liezen, Austria with his family