Mike Campbell-Jones has been flying for 30 years and designing paragliders for 20. A former instructor he founded Paramania and helped to develop the reflex paraglider. In his column in issue 165 he discussed our flying playground

The abbreviation AGL = Above Ground Level, is where all flying activity takes place. For pilots, the sky is a wonderful 3D playground, yet since the development of the paramotor, our flying world is expanding at the same risky rate as our equipment. Paramotoring is unlike other aircraft in that it’s forgiving enough to be possible to fly safely at all levels, as long as our equipment adapts to our growing trends in low-level flight.

Altitude = Time

It goes without saying that the higher you are, the safer you are. Pilots encountering a major deflation at cloudbase have ample time to react, choose a landing and release a reserve if need be. It’s also easier to navigate at altitude as there’s less risk of getting lost; the ground simply looks more like the map.

So the message is clear that in most disciplines of aviation, including our sister sport of paragliding, height definitely equals safety. But although the open sky is safe, it can also become less exciting; as the perception of speed changes with elevation, you appear to be flying slower and slower until you feel stationary, floating nearly motionless in space.

The growing trend

Nowadays it seems that everybody prefers to play around at twice the tree-top height. Although it’s more interesting, it’s also risky. So why do we choose to fly at lower levels?

1. A psychological separation

Our connection with our planet is a factor in our enjoyment in the air. The vast endless sky can be a lonely place, and it’s in our nature to crave familiarity. Being up in the clouds can therefore be a little scary because we are separated from Mother Earth. Since many paramotor pilots fly alone, the higher they go, the lonelier they feel.

2. The illusion of safety at low levels

Contrary to what people might think, flying very very low is actually very safe – at two metres above the ground, there’s not much that can happen if you fall on the ground, and an engine failure means at worst a hard or quick landing. On the other hand, the lower you are, the rougher the air is. Air on the surface is influenced by mechanical turbulence and ground air friction, which unless you’re flying in nil-wind, can make for a bumpy ride.

3. The thrill of speed and adrenaline

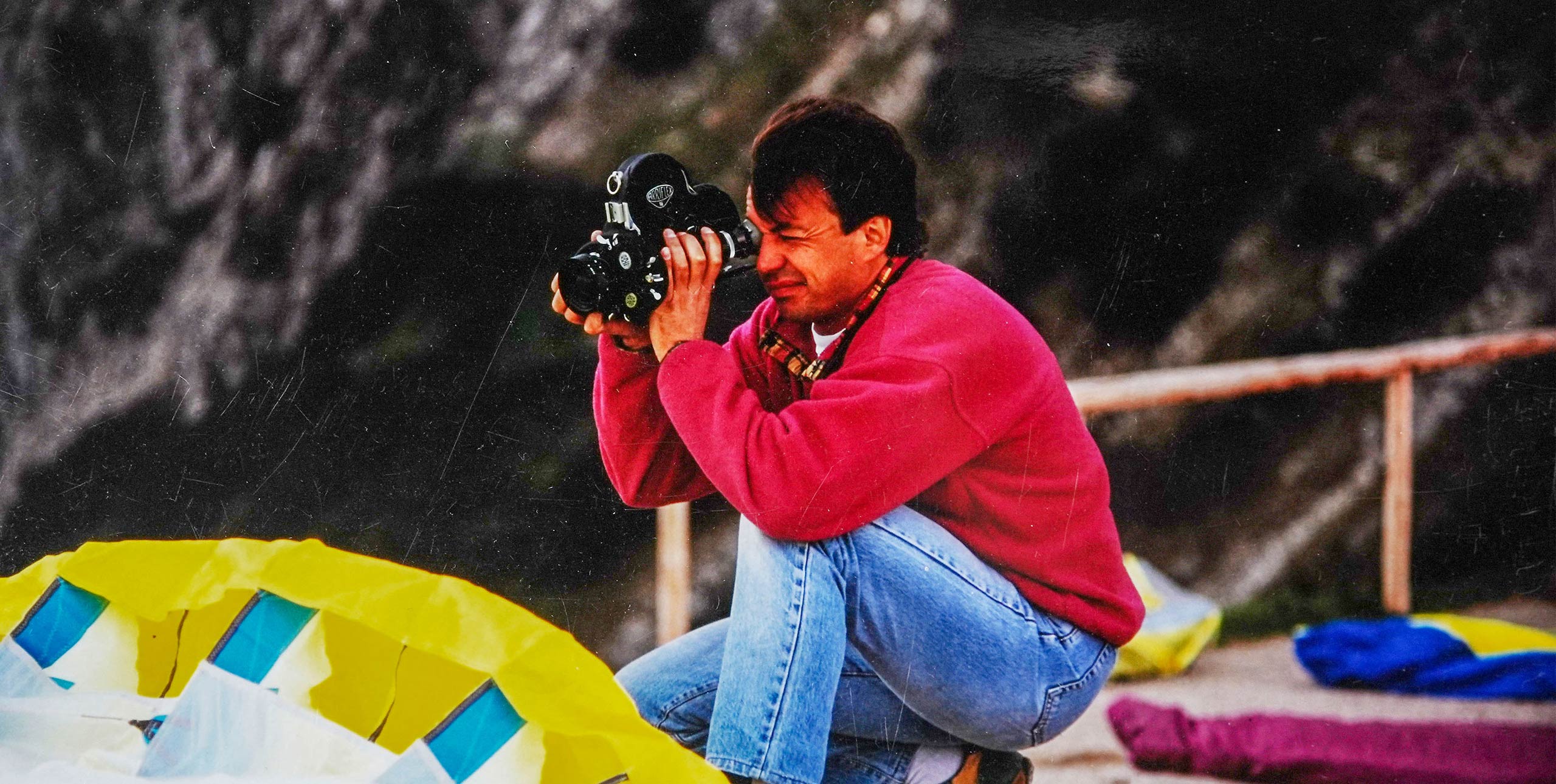

Many paramotor pilots enjoy risky flying close to the ground. Racing between trees feels much faster than it is because the ground is going past so quickly. With stronger, lighter equipment and ever-increasing performance, pilots are getting bolder too. And besides, who can resist the desire to show off during a perfect sunset, a rare opportunity to fly with friends and a willing cameraman on the ground?

The pursuit of performance

In our quest for fan-worthy photos, we increase our chance of accidents.

To potential pilots, an incident report can determine the choice to opt out of the sport, and for every person that has an accident, there’s a thousand who don’t fly.

As we strive to fly ever closer to the ground, the equipment we use needs to adapt to meet the urgent need for safety. As the handling of wings and the reliability of engines improves, designers need to consider the growing trends and dangers of low-level flying, and not sacrifice safety for performance.

Safety in design

A paraglider tends to be long and thin, designed to maximise its lift and thermalling ability. While this is great for agility, the migration of technology from paragliding blindly affects research because it gives more performance in certain parts of the speed range.

The longer and thinner the wing is, the more likely it is to have problems reopening or recovering after a collapse. This is detrimental to paramotoring, where lift and thermals are not applicable in smoother air when paramotorists prefer to fly.

If we’re flying too low to pull a reserve, the wings have to be more collapse resistant than ever before. Our sport is begging for improved safety margins, and it can start with a lower aspect ratio.

Trusting your life

Paramotoring has stretched our flying playground to lower, more dangerous altitudes, and the trend will continue as high performance wings continue to tempt pilots into the latest thrill ride. But when considering the risk, paramotoring must be treated as seriously as parachuting; you wouldn’t risk jumping out of an aeroplane if you worried your parachute was going to fail you in the final 300m approach; you should be able to trust and rely on your paramotor equipment with as much confidence.

If paramotoring is going to have a future, our wings cannot afford to collapse. Lets see the sport thrive, and keep our pilots safe anywhere AGL.

If you enjoyed this sample article, perhaps you’d consider subscribing? A subscription is also a perfect gift for any pilot! Cross Country is a reader-supported international publication

Subscribe and receive 10 issue in print or digital, and we’ll also send you a Cross Country Wallet pre-loaded with 10 Euros to spend at xcshop.com