Yassen Savov flirted with fire in the PWC Superfinal in Colombia in 2013. We published his story in issue 146 of Cross Country magazine. As the issue of flying in fire thermals raises its head again at the 14th FAI Paragliding World Championships, we publish his amazing story online.

By Yassen Savov, former European Paragliding Champion

Things didn’t start great for me at the Paragliding World Cup Superfinal in Roldanillo. After two bad tasks I was thinking it could only get better, but I was wrong. Here is what happened on Task 3.

On take-off we are unlucky to have backwind, so lots of YouTube moments there. Too bad for me – I am one of the last pilots in the queue. My turn comes with only 18 minutes to the air-start, quite late. Meanwhile, the backwind is increasing. I have to try, otherwise I’d be risking being grounded while the others are starting above. I pull the wing up. It inflates well, but when I turn around some slack lines catch me by the neck, while I am already running full speed. First time ever that happens to me. I guess I am lucky that I crash before taking off, otherwise I imagine the line could have even cut my neck.

Anyway, I tumble on my stomach and roll down quite hard, my new GPS instrument flying away from the cockpit to its death, the other one also breaking but not completely dying on me, and my harness suffering a large gash in its top surface, leaving my cockpit flapping down like the stomach of a ripped frog.

I feverishly stumble back up to try again, only asking my friend Jorge Atramiz to hand me the duct tape from the back of my harness, and with 13 minutes to the air-start and the same weak back wind, I pull the wing again, and, with the lines brushing my face again, I manage to fly away. Some stressful shit, the whole thing.

Felix Rodriguez in a fire thermal at the PWC Superfinal 2013. The action starts at 0:50seconds.

I guess I’m quite sweaty, but I have other matters to focus on. Immediately after take-off I start taping my cockpit back into place – it kind of works, so I start climbing to try to make the start on time. That also kind of works. And the race is on!

I don’t have my good instrument anymore, and I am still quite disconcerted from the stressful take-off, so I start the race trailing by 1-2km behind the leaders. Between second and third turnpoints however I make a different move from the main group, which allows me to almost catch them from the side, but only almost, because I am suddenly sinking very, very hard.

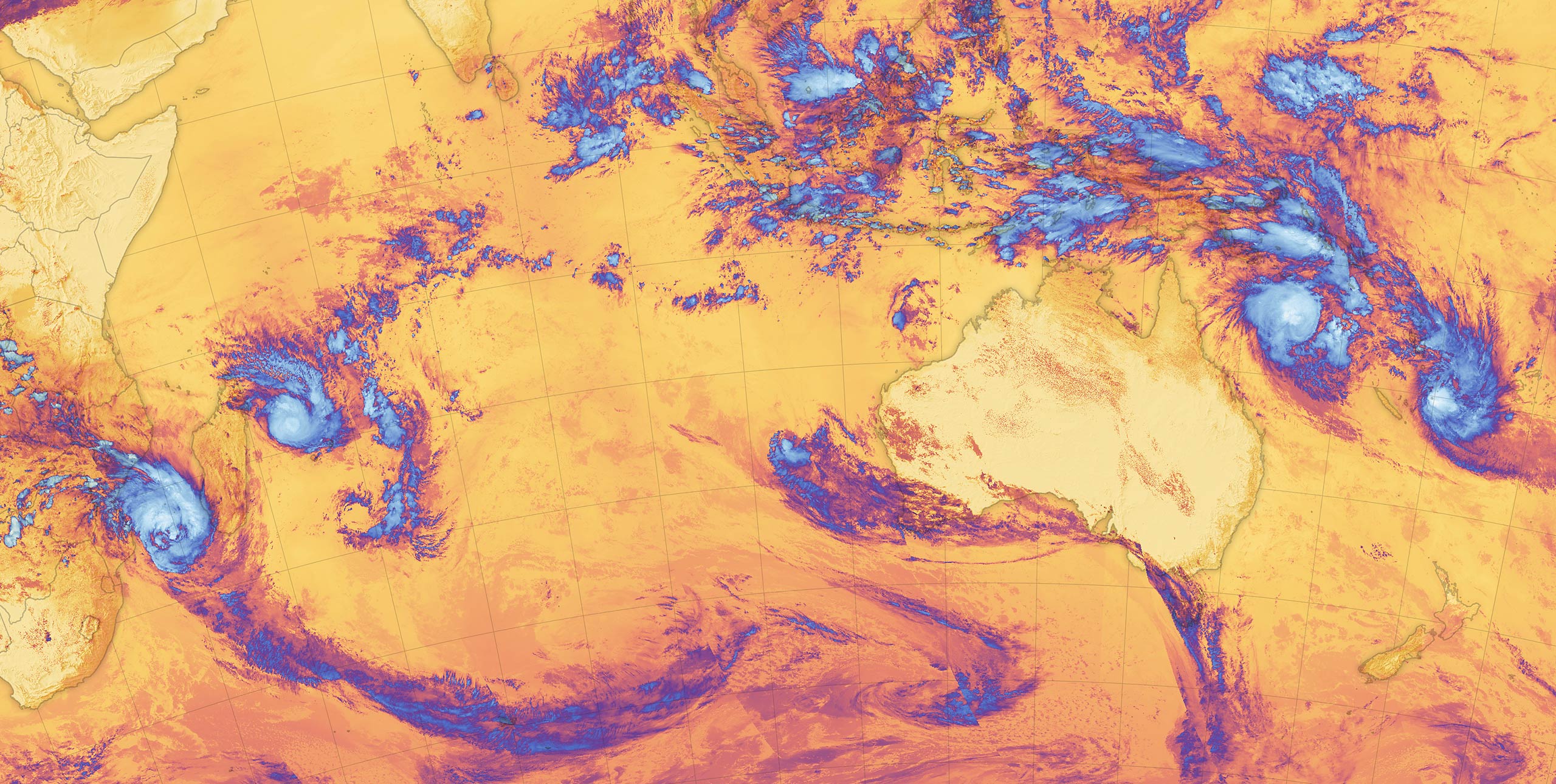

So there I am desperately bricking with 4-5m/s down, and aiming for the one and only obvious target, and the reason for my sink – as I am flying in its downwash – a massive fire that farmers have set in the freshly harvested sugarcane fields, flames more than five metres high, fuming a huge black column of ash. I am about 500m in front of the first group and 300m lower than them, as I am about to reach the fire with a little more than 50m above the flames – a height quite worrisome when considering the dramatic setting. However, the day before that was the height that Aaron Durogati needed above another fire that allowed him to climb from where the rest of us landed, and win the day.

That day I had decided it was not a good idea to go for the fire. But today I don’t want to land again next to another damn fire, while the others climb above my head again. Plus, after having seen Aaron climbing above the first fire without too much trouble and turbulence, I judge it can’t be too dangerous. So I go for it. But, plunging into the blackness of the rising ash, I don’t find the strong and turbulent, but manageable, fire thermal that Aaron had found the day before. No. What I find in there is probably the most horrifying experience in flight I’ve ever had. It is not a thermal, it’s a nuclear bomb (fuelled, I later find out, by the petrol poured by the farmers over the already dry sugarcane).

The first metres above the flames feel like a huge swirling dust devil, only instead of dust there is fire and ash. Fire devil! As soon as I have entered I realise it has been a very, very bad idea, as I start experiencing the first moments of the most intense thermal of my life – peaking at 16m/s vertical speed, I later see on my GPS recording – and I can imagine myself losing control of my glider and falling into the flames, burning hopelessly fast, wrapped in the six kilos of highly flammable nylon that is my paraglider.

So I stay calm, using all my power and experience to keep the glider flying, despite the incredible power from below thrashing it in all directions and shapes like a flying plastic bag. I can hardly see anything because of the ashes, but I’m focusing on the only thing that matters at that moment – my glider. Battling hard, in a sitting position in order to minimise the chances of getting spun, somehow I manage to keep it (kind of) flying.

Less than a minute later I guess I had shot up more than 700m, half-way to cloudbase. The stream of ash is getting less dense, as I’m escaping the raging flames below me at 40-50km/h vertical speed, and the brutally strong air current smoothes down. I start seeing the first gliders from the leading group a couple of hundred metres away, on the downwind side of the fire, while I am right in the core – they all shooting up like Chinese fireworks, bending around like paper, like rubber toys in the hands of clumsy children.

Anyway, I realise that I have probably survived the situation; that, worst-case scenario, even if my glider collapses and goes into a bad cascade, I probably wouldn’t fall straight into the flames, but would be able to open my reserve and probably fall on the side. The air is getting manageable, it’s starting to feel more like the strongest thermal of my life and less like a nuclear explosion below my ass. So I start re-focusing on the task at hand – I am in a competition, I am alive, and the race is still on, so use the rocket for another 40 seconds to climb to the top before charging forward!

But, surprise! As I am circling already more than a kilometre above the fire, in the space of less than five seconds, first I glimpse a cloud suddenly forming 50-100m away, not above but around me, and two seconds later I am suddenly engulfed in it. I don’t see it coming at all, it just explodes into shape and existence around me.

So off I go straight on course line, trying to escape from the white room in the same super-strong thermal air, now white, and keep on course towards the next turnpoint, even though I can’t see my GPS, which has in the mayhem fallen off towards my knees together with the duct tape that was holding it in place. But I can’t keep the straight line for long, as in the next moment I simultaneously see my glider fold down towards me in a disastrous shape, and I feel zero gravity. I’m literally falling off the side of the turbo cumulus.

A moment after that my glider reinflates behind me with one or two cravats, then shoots down below me, but not enough for me to fall inside, then comes back above me and in the next moment quickly spins above my head, keeping that movement despite my efforts to prevent the twist of risers; and I’m pushing the risers apart in an effort to untwist myself, and then I feel them closing on my right hand, trying to lock my only rescue-throwing hand! If I’d been one second late trying to remove my hand, it was getting locked-in up high in the single rope that my risers are creating – throwing my rescue would have been impossible. Fortunately, I move it away on time.

However, the spin is already out of control, I can’t even begin to untwist myself, and with every second the glider is twisting again and again, it’s too late for me to reverse the motion. A minute later I am spat out of cloudbase, so I start thinking about when to throw my rescue. First time in my life to throw while doing cross country. The only problem is I am still directly above the fire.

So, still close to cloudbase and with 1,000m to the ground, I decide to wait until (hopefully) I get drifted by the wind to the side of the fire. Around 500m later I have drifted enough, so it’s time. I wait for a moment when the rotation slows down a bit, and I throw. But the glider is still rotating, so by the time the rescue is slooowly opening, it has already started rotating around the glider. Not good.

I push the still slack rescue lines away, two more seconds, and I feel the reassuring pull of the rescue and my arms and head getting stuck between the now four risers of glider and parachute.

With 300m more to the ground I manage to free my upper body and start collecting the glider by the rope that have become its two risers. I manage just about to keep it quiet and not moving around too much, when the ground comes and I take the hit like the Bulgarian ballerina I am – graciously rolling back from legs to back, spreading the energy nicely. Get up, no injuries, alive!

I pack my glider and rescue among the sugarcane workers and heavy sugarcane bulldozer-trucks, in the close-to-40-degrees heat of the Colombian working man. Finally, back in HQ, I see that my camera, without getting hit in any moment during the chaos of the flight, apparently by coincidence, has also stopped working (“system error zoom”). Today that could be expected. With both my instruments broken from my fall on take-off, I don’t have any fully working GPS to download my track from, so Ulric Jessop, the scoring man of the Paragliding World Cup, has to use my live tracker in order to salvage a few points for me for the ranking. But I couldn’t care less about the points, the happiness of survival is much stronger. I feel like Dante’s phoenix, risen out of the fire of hell, and flying again.

• Got news? Send it to us at news@xccontent.local