The latest issue of Cross Country magazine (issue 159, May 2015) features an incredible 7,500 word essay on wingsuit Base jumping by wingsuit pro Matt Gerdes. Matt comes from the world of paragliding (indeed he works for Ozone) and is now an expert voice in the close-knit world of wingsuit Base jumping. In this essay he takes us inside the mind of a wingsuit pilot as they prepare to jump – from first steps to time stopping when you make the leap…

For me, in a way, it all started with the Eiger… and with Jimmy. We were paragliding in the French Alps back when Jimmy was a new Base jumper and I barely knew what the sport really was. It was a cold and humid day in May with just a bit too much wind for flying, so we were lolling around in the grass at St Vincent Les Forts.

I was watching him pack his Base canopy. He looked up at me, excited, and told me that he was going to Base jump the North Face of the Eiger in August.

I was stunned. “Is that even possible?” I asked. Yeah, it gets jumped quite a bit, you just have to walk up there. My astonishment rapidly morphed into excited determination, “Can I come?” I asked.

“Sure,” he said, “but you have to learn to Base jump first.”

Five days later I was sitting in a Pilatus Porter, climbing to altitude over Gap-Tallard, France. I only had a few days in Gap-Tallard with my instructor, a calm and level-headed Englishman by the name of Kevin Hardwick, in which time I completed 11 skydives, which was about 200 skydives less than the generally accepted minimum to begin Base jumping.

But, I figured, with 1,000 hours flying paragliders and my superhuman outdoor sports skills, I’d be fine. I was young, and foolish.

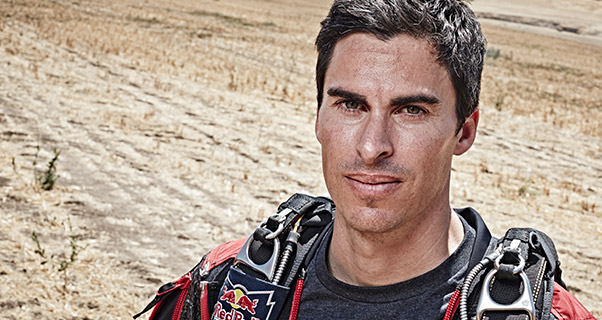

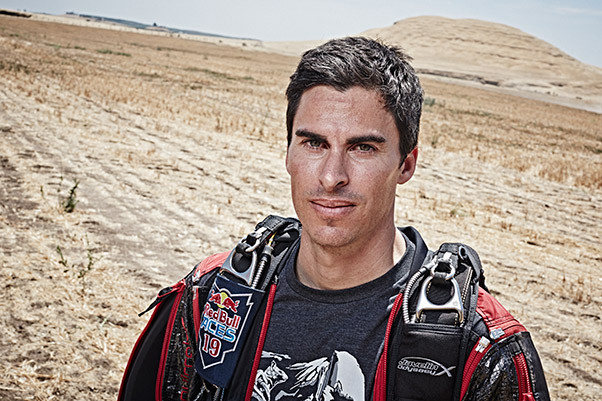

Matt Gerdes flies the Brevent in Chamonix…

Skydivers, for all their long-haired left-leaning yahoo-screaming tendencies, are a dogmatic and hierarchical group. They set rules and, for the most part, live by them and enforce them upon each other. Experience and capability in skydiving is often defined with jump numbers, and a skydiver with 500 jumps will normally be considered better than a skydiver with 300 jumps, even though the opposite is often true depending on the person.

If the rulebooks states that one needs ‘X’ number of jumps to try a new skill, then there is usually someone inspecting your logbook when you want to try it. If you have a question or a problem, you refer to someone with more jump numbers than you.

Most Base jumpers are experienced skydivers first, and traditionally skydivers were not allowed to even think about Base jumping until they had years in the sport and hundreds of skydives. The subtleties of canopy flight for landing, and body flight in freefall, require much time to master.

Thus, with just 11 skydives and virtually no time at all in the sport, I was seriously breaking the rules by planning to Base jump. Fortunately for me, I knew people.

A good friend referred me to his good friend, Greg Nevelo, who was willing to not only teach someone with so little experience, but take time out of his schedule to drive 17 hours with me to the Perrine Bridge in Idaho, where Base jumping is legal and accepted.

The Perrine Bridge spans a gorge through which the slow-moving Snake River meanders, 150m below. It’s not a huge jump by any means, but the legality, ease of access, a nice landing zone on the riverbank, and the water itself all make it an ideal place to learn the basics of Base jumping.

Although hitting the water at 150km/h will be the fatal result of failing to deploy a parachute, the water does provide a certain amount of protection against canopy malfunctions and late deployments, if they occur. The Perrine Bridge now sees more first jumps than any other object in the world and is generally considered one of the safest jumps on earth, yet five jumpers have died there in the past 10 years.

As I climbed over the railing and looked down to the green water below, I was filled with 60% fear, 30% excitement, and 10% ‘what-the-f88k-am-I-doing’ doubt. Officially, I should have been skydiving for at least a few months, if not a few years, and I should have had over 200 skydives already under my belt.

But I was committed. Greg was calm, and I could almost hear his instructions over the sound of my pulse. My mouth was dry, and my hands were wet. Knowing that I wouldn’t become less scared by standing there, I left the bridge, fell into the dead windless air, and time ground to a halt.

A falling body accelerates from 0-100km/h in just three seconds. At about 10 seconds, acceleration levels off and we’re hurtling toward the earth at almost 200km/h. It is a curious fact that although during this acceleration physical time is generally static, mental time can be elastic.

Stepping into space, hundreds of metres over the ground, time bends. A minute’s worth of thoughts pass through your head in the first millisecond, but at the same time you are so focused on only this, only the jump, that you’re thinking of nothing.

It is a level of focus that could be compared to a Zen master in deep meditation, and all you need to do to achieve it is commit suicide with a plan B. My mind races, constantly, in a ceaseless internal dialogue that has plagued me since pre-adolescence.

Matt Gerdes on the Eiger

I have only ever found solace while in situations of agitated excitement; states of mind that came most easily while rock climbing, back country skiing, or whitewater kayaking. While I’m doing something that requires my full attention in order to prevent serious injury or death, my mind is at ease. And Base, I realised instantly, was the ultimate in neurological satisfaction.

As my feet stepped into nothing and my mind relaxed into intense focus, I wondered what was taking so long for my parachute to open. That second felt like a half-minute, and as my parachute banged open and the opening forced my chin to my chest and my gaze downward, I realised that I had fallen barely 50m and now had over 100m remaining to steer my parachute to landing.

I touched down in the field and instead of feeling like I had just accomplished something I was overwhelmed with a sense of having taken just one small step of a long and serious journey. I made seven jumps at the Perrine Bridge over a couple of days, and then got back on a plane to the Alps. I had Eiger fever…

The full story is in Cross Country issue 159, May 2015

• Got news? Send it to us at news@xccontent.local

If you enjoyed this and want to read more, consider subscribing to Cross Country.