A year ago this October Canadian competition pilot Brett Hazlett had an accident while launching from Babadag in Turkey. A year on he re-lives what happens, and takes us step by excruciating step through his painful recovery. The goal: to fly again.

I am lying on the steep slopes of a six-thousand-foot mountain in Turkey, in intense pain, struggling to breathe, unable to move.

How did I get here?

I’m writing this from my hotel, headquarters for the Paragliding World Cup event in Disentis, Switzerland. All this feels so long ago. Today was the first task. What a task!

I’m doing well. My life is better than ever. This last year, though, was difficult.

I was at the Paragliding World Cup Superfinal in Denizli, Turkey. After a week without flying, yet another cancelled task. We went to Oludeniz to enjoy the beach and free-fly. I intended only to take a few photographs of the bay and enjoy the cool coastal air. I was frustrated, dehydrated, and feeling time pressure. The bus for Denizli would leave in an hour.

Launch conditions had deteriorated. For some time it was blowing down, steadily. I moved to the other side of the mountain, to launch from a turn-around in the highway, but into the wind. Past the shallow highway was a cliff. The exit past the cliff had obstacles: a tree on the left and a rock outcropping on the right. The wind became light, perhaps 3km/h. I went for it, got airborne, but missed the exit, hitting the tree on the left with my body, past the edge of the cliff.

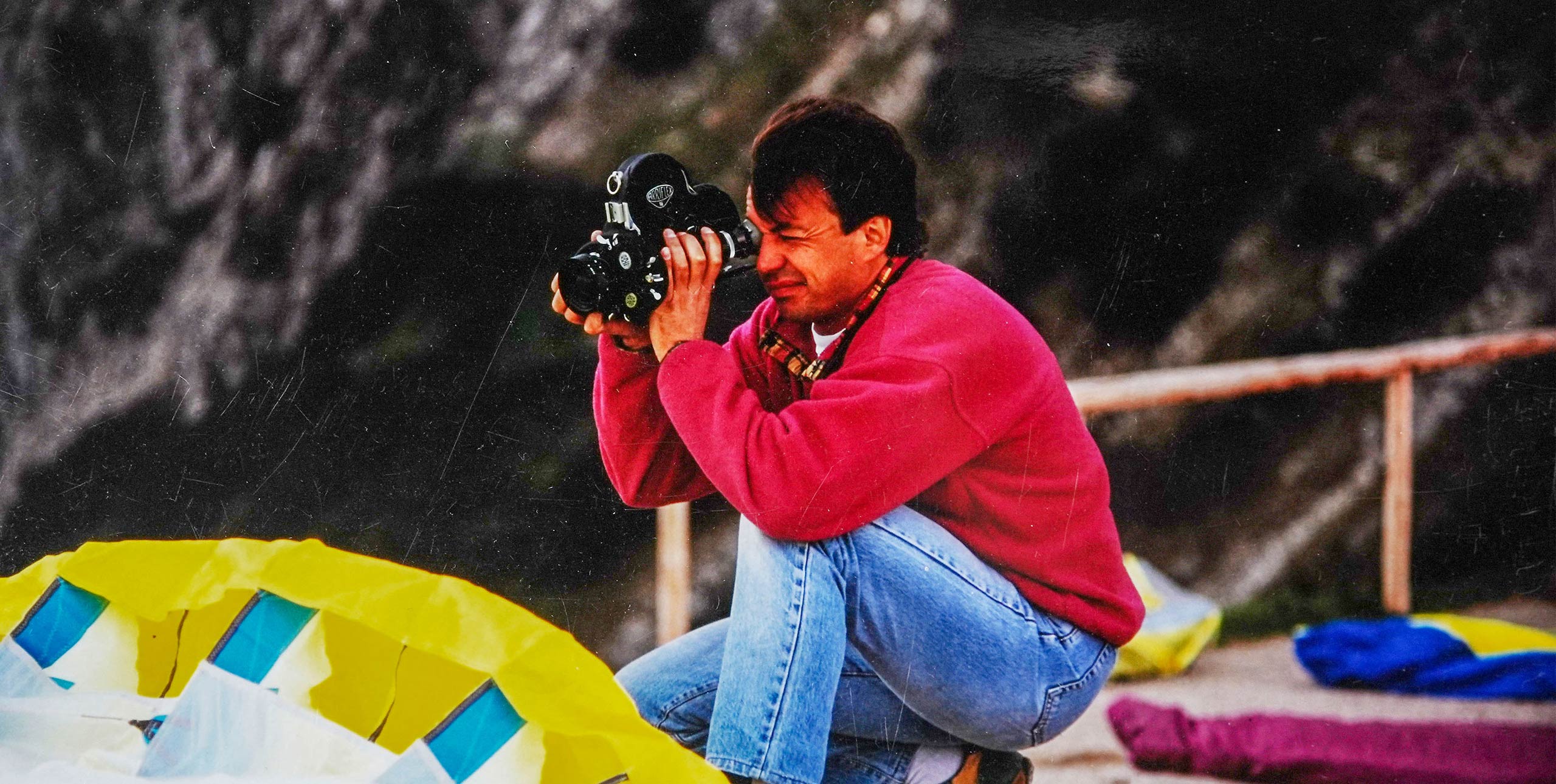

Brett Hazlett in competition mode in Switzerland this summer.

Photo: Martin Scheel

Falling. Just one thought in my mind: Not like this. The speed was terrifying, the impacts brutal. The terrain was steep and despite the impacts I wasn’t slowing. On the fourth impact I suddenly came to a stop – my glider grabbed a small tree.

I was lying on my side. My helmet had released from my head. I listened as it bounced, skipped, and spun down the mountain, until I could no longer hear it. Dirt and gravel continued to slide past me as I lay on my side, struggling to breathe. I closed my eyes and focused on breathing. Slowly, deliberately, shallowly.

The Search and Rescue team were on the top of the mountain and were helping me within minutes. So many people helped me. People I knew, people I didn’t.

I was confident I hadn’t suffered a head trauma. I could move my toes. I sensed my blood pressure was healthy. I smiled, feeling grateful to be alive, and despite experiencing intense pain, thinking I would be better soon. I was right, although ‘soon’ became a year.

To die is easy, surviving is difficult.

I had compression fractures of my T10, T11, and T12. The PCL in my right knee had detached. I had a Type 2 fracture of the talus in my right ankle.

The first hospital misdiagnosed me. I was asked to stand, I refused. A friend forced my discharge and brought me back to Denizli, where I spent a day coordinating with my insurance company to be moved to a private hospital in Antalya.

My surgeon recommended operating quickly, to reduce the possibility of avascular necrosis developing in my ankle. The operating theatre was available. He gave me thirty minutes to give consent. I did, signing thirteen pages, all in Turkish. There wasn’t time to contact my family. I remember staring at the bright lights in the operating theatre and beginning to tear, wondering what was going to happen to me. A woman leaned over, removed my rings, and gestured by blinking slowly that it was time to sleep.

I blinked slowly, nothing was happening. Nobody had touched my IV. Was I supposed to fall asleep myself? Another blink, then another. My eyes opened again. It was over. I was on the top floor again, in my room, my surgeon and a number of nurses were finalising the bandaging of my leg. For me, no time had passed. I smiled. I’m still alive! Rods protruded from my right leg. More rods and cams connected them. It was a monstrous sight. I developed a fever which had to be managed through the nights for a few days. This was the start of what would become a three-week hospital stay.

In the mornings I watched the only English channel available: CNN. About fifteen minutes of news looped all day. Mostly, it was about the ebola outbreak and ISIS siege of Kobani. Kobani wasn’t too far away.

I couldn’t roll onto my side. I lay on my back all day, sweating, unable to change position. When I closed my eyes I would feel my right leg being twisted in a horrible way. When I opened my eyes the feeling disappeared.

The days seemed to never end, as I watched the shadows of objects in the room arc across the floor from west to east. Alone.

One afternoon I felt panic arising. I just couldn’t be there anymore. I had to leave. But I couldn’t even roll over. If I waited until late, I could crawl out of the building. Even then I would be alone, in the middle of Turkey, on the wrong side of the planet.

One dawn, as I watched a pink sun rise above the horizon in Antalya, a small bird landed on my windowsill, sung loudly for a few moments, and then flew away. From that moment, I felt intense resolve.

Before my accident, I felt like my life was a task of juggling 20 things simultaneously to keep everything going smoothly. Each thing seemed to have a similar value. After my crash, I realised that most of these things had almost no importance to me. A few things had extreme value. I could walk away from most of my life and not look back. Instantly, my life was no longer complicated, it was simple. It always was.

Three weeks passed. A nurse escort arrived from Canada to bring me home. In my condition, the 24-hour trip was arduous. Finally, I was home and grateful beyond measure. It was a celebration but the work was just beginning.

At week six the external fixator was removed from my right leg. I declined anaesthesia. Midway through the procedure I regretted this choice. The two metal rods came out of my tibia without complication. I sweated and requested frequent breaks but was doing well. A nurse said I looked pale.

There was a metal rod going through my heel that needed to be removed. Unfortunately, it had bent slightly and was jammed inside my heel bone. The doctor and three male nurses spent the next 30 minutes twisting, pulling, and banging with tools that resembled a car mechanic’s but in stainless steel. These thirty minutes recalibrated my 0-10 pain scale. Ten is not what it used to be. When I felt my blood pressure drop I would call a time-out, drink some water, wait a minute, and then call them back to continue. Each millimetre was hard-earned.

I couldn’t walk for five months. I lost twelve kilograms. Each day, excruciating physiotherapy. My doctors explained that most likely I would not be able to walk on uneven ground or run. I might need to use a cane. My physiotherapist’s previous patient, with a displaced talus fracture, eventually elected for amputation because his pain levels remained too high to bear.

When I was alone, I cried. I would wake up in the middle of the night and have to crawl on my hands and knees to the bathroom.

What is going to happen to me?

I no longer had flying dreams, only walking dreams. I would find myself walking slowly along a forest path, at night, under a full moon. Gradually, I would become aware that I was walking and, elated, would look down at my feet to watch them move. As I did I would begin to wake up and find that I was lying in bed, having woken from the dream into the nightmare.

I read studies of the rehabilitation of patients with my injuries. The news wasn’t encouraging. I browsed forums related to my injuries, looking for encouragement, but only found darkness. I would remain depressed for days, not getting out of bed, only staring at the winter rain falling outside.

I had to stop.

What happened to 15 research subjects who suffered similar injuries to mine is neither important nor relevant. I made a decision: I must give all my attention to what is happening to me now, now.

I went back to the gym to lift weights. I had to use Nautilus-type machines, of course. I would use my crutches to move between machines, as people stared. Weight training, physiotherapy, and cardiovascular training became a two- to four-hour segment of each day.

I took my nutrition to a new level of discipline. Training was difficult when I was uninjured, now it was much harder. The pain was so loud that the normal discomfort of lifting weights became insignificant. On the outside, I avoided eye contact and remained quiet. I had to keep to myself to contain the pain. Inside, I screamed in rage.

There was the trauma of the accident, the trauma of the operation, and the trauma of the rehabilitation. Each stage involved pain and opportunities to fail.

I have a new relationship with pain. I consider pain a close friend. Not a friend I chose voluntarily but one I had to get to know. Although usually obnoxious, he has taught me many things. Not lessons I fancy at the time but valuable lessons nonetheless. Hard lessons.

Slowly, very slowly, steps. Gentle steps. Then more. I regained the strength I lost. Soon, I was flying. My first flight was neither anxiety-arousing nor exhilarating. I enjoyed the early spring flight the way I usually enjoy a nice flight. It was rather anticlimactic but was still the culmination of the most immense personal effort I have undertaken.

Why fly again?

My family was worried. My friends were worried. Before, they thought I was invincible. Afterwards, they expected me to crash each day I flew. Both positions are unrealistic.

I wondered what stops me from doing things. Fear of pain, of suffering. Fear of dying. Well, not the dying part, the dead part. Being dead. The fear of my person dissolving into nothingness. I can’t experience being dead – I don’t think so anyways – yet I fear it. Is this insanity? How can a sane man fear an experience of something that cannot be experienced?

Pushing away from suffering, resisting my mortality, alienates me from the human experience of living. The juice, the honey, is in becoming intimate with death. Intimacy with death is intimacy with life: the process of life.

If I hold my life delicately in my cupped hands, will I avoid death? Will I never have to say Goodbye?

No.

One cold and wet winter night, alone, I watched my flying videos – all 68 of them. The magic of my twenties and thirties reanimated in my mind. The images and emotions so vivid I drowned in a waterfall of well-lived days. The beauty and adventure beyond description! Tears rolled down my eyes. How much more is still waiting for me?

I was left with clarity. There was a choice to make: withdraw or continue.

For now, I choose continue.

If you enjoyed this sample article, perhaps you’d consider subscribing? A subscription is also a perfect gift for any pilot! Cross Country is a reader-supported international publication

Subscribe and receive 10 issue in print or digital, and we’ll also send you a Cross Country Wallet pre-loaded with 10 Euros to spend at xcshop.com