Meteorologist Honza Rejmanek explains the phenomenon of Heat Lows, which can cause the wind to unexpectedly increase in the valleys on hot summer afternoons.

One hot summer day you decide to visit a site that is rarely flown. The synoptic situation is benign. Your region is under the influence of a subtropical high and the morning sounding indicated light and variable winds.

The sweaty hike up, and a lack of what most would consider landing zones, ensures that this tight little launch never gets crowded. The site is located in a coastal mountain range approximately 60km inland from the ocean. The equator-ward faces have dry grass and shrubs, the pole-ward faces have shrubs and a few trees. Arriving at 3pm you find conditions to be quite reasonable. The lake below has some texture but no white caps. Cycles are strong but not crazy strong for your skill level.

You launch by 3.30pm figuring that thermals are now past their peak and you hope to enjoy a nice afternoon flight. Indeed this turns out to be the case. The thermals allow you to gain height quickly and you start to contemplate a late afternoon XC.

By 4pm however you notice the texture on the lake below change rapidly. White caps are now evident and you realise a strong wind has arrived below you. There is no time to be surprised. It is time to run. Fortunately you are more than 1,000m above the terrain and within glide of an open landing area. You manage to fly ahead of this low-level wind and you land safely before the strong wind reaches your landing area. “I can see why hardly anyone flies this spot!” you tell yourself. Having walked away from what could have been a good day gone bad, you become curious to why a strong wind came in so suddenly during a part of the day you were expecting things to start mellowing out.

How a heat low forms

After listening to your story a fellow pilot suggests that a ‘heat low’ might have drawn in the afternoon wind that caught you off guard. This seems contrary to what you saw on the morning surface pressure chart. Where would the low have come from?

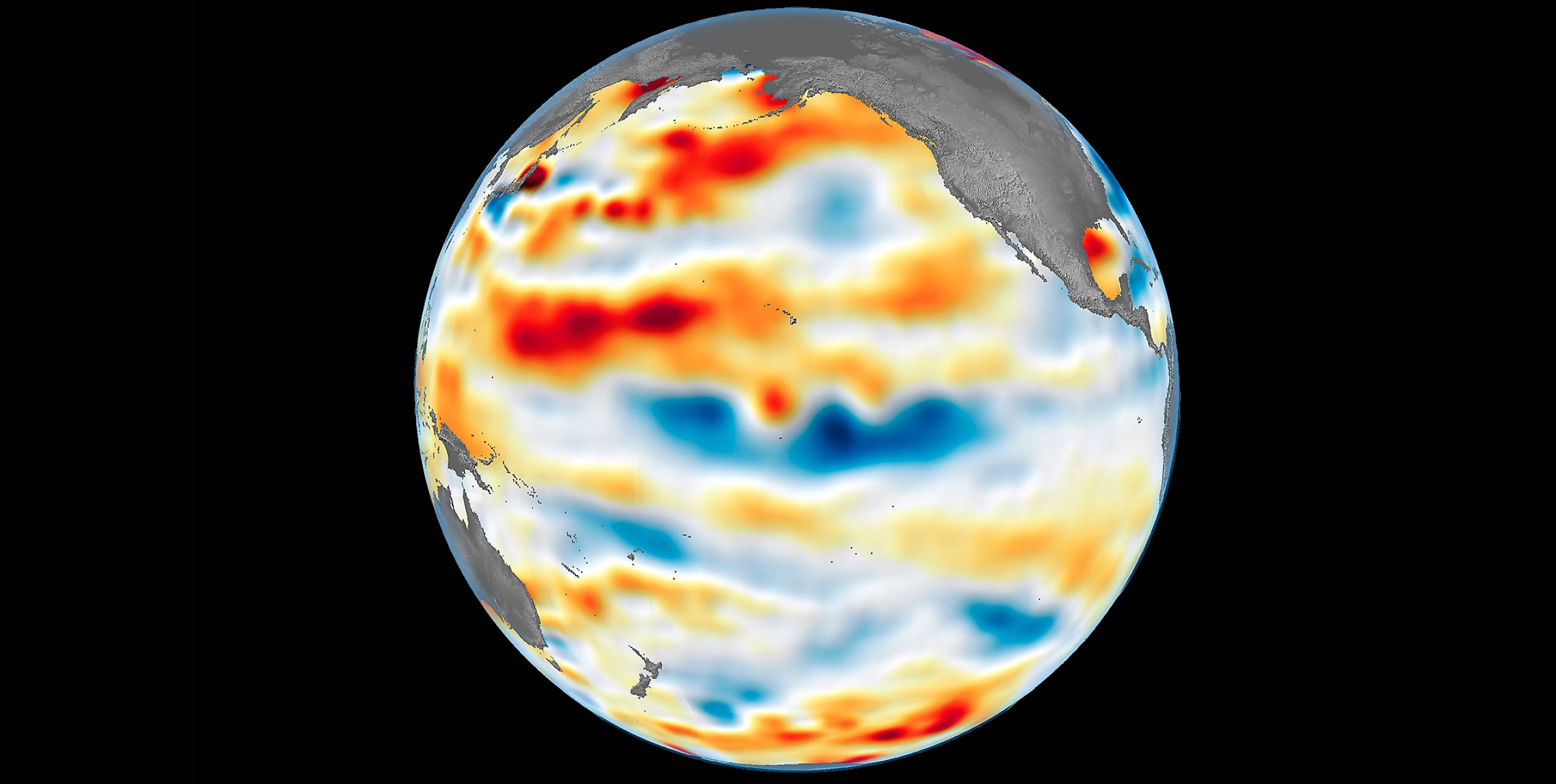

Upon further research you learn that a heat low, often referred to as a thermal low, is actually a fairly common diurnal phenomenon in dry subtropical regions. It can also manifest itself in mid-latitudes in the summer months. In many places such as the Iberian Peninsula, Tasmania, or the central valley of California thermal lows form frequently in the summer months, often when there is a semi-permanent high offshore. A strong sun, clear skies and a semi-arid surface are all requisites for the formation of thermal lows.

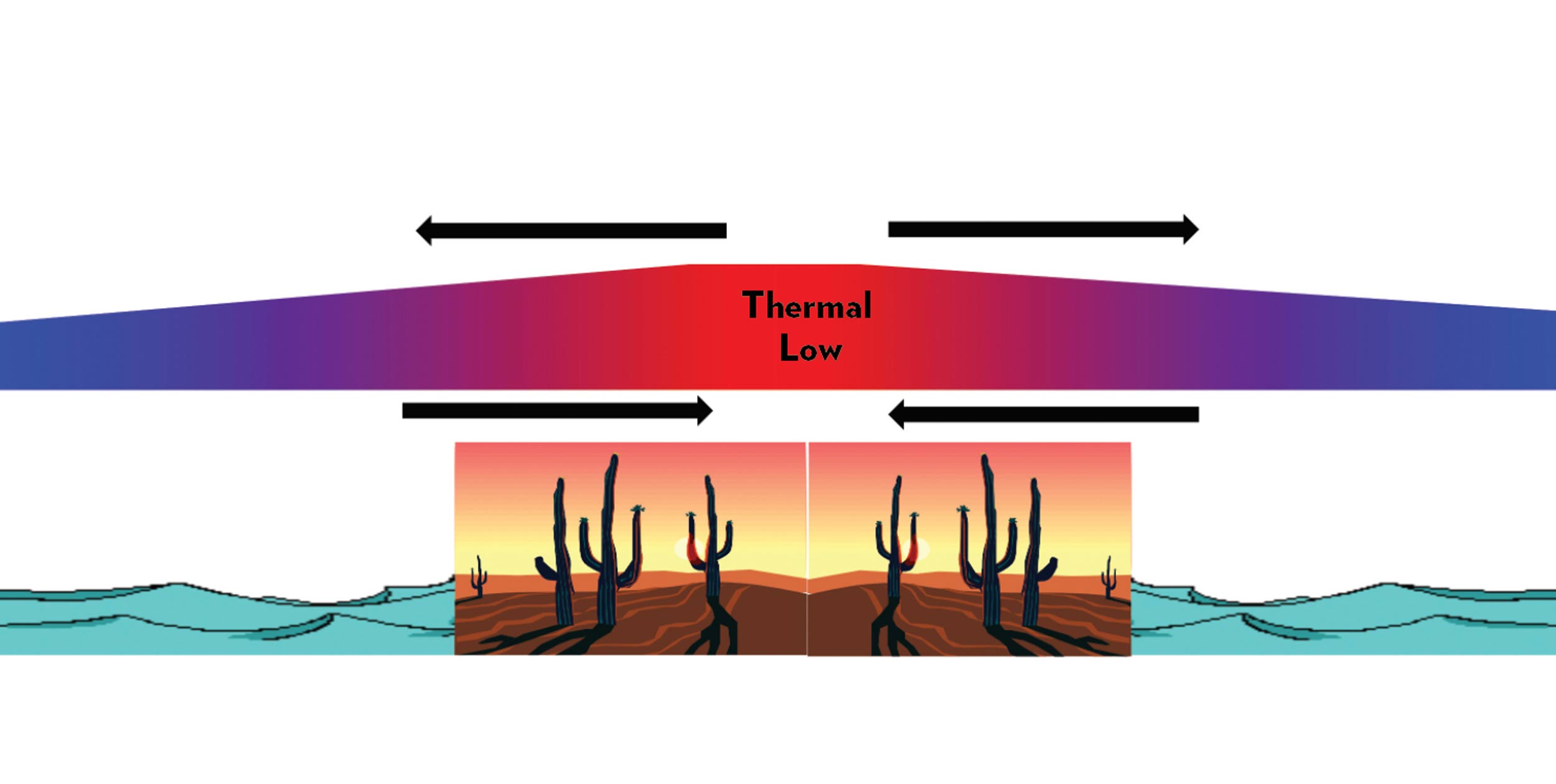

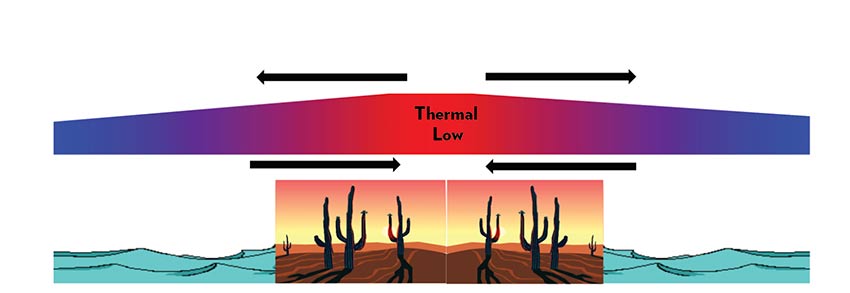

The strong heating of the land surface by the sun results in thermals which in turn warm the boundary layer. Thus the lower levels of the atmosphere become less dense. As the air become less dense it expands and this results in an outflow above the region receiving the intense heating. Often this outflow occurs at the 2-3,000m level. The divergence at this level results in a decrease of pressure at the surface. The developing pressure gradient eventually results in a low-level breeze that starts to blow in from cooler regions like an adjacent ocean. Despite the strong sun the surface temperature of a large deep body of water does not change very much over the course of a day.

Evening schedule

Most thermal lows follow a daily schedule with the lowest pressure occurring around six in the afternoon. Overnight the lows diminish in most places. Over large dry continental areas such as Australia and Northern Africa deeper thermal lows can develop. These can persist into the night and they can become mobile.

Focusing on the thermal lows that tend to follow a daily schedule it makes sense that surface winds begin to blow inland as the low intensifies. Channelling effects due to topography can cause these surface winds to reach speeds over 10m/s. This is where flying a new site in the afternoon hours can catch a pilot off guard. Just because the heating rate is diminishing and the thermals are starting to mellow does not mean that the winds are going to follow the same schedule.

The strongest pressure gradient exists around 6pm and the resultant winds can peak around sunset or later, depending on the particular location. By 6am the thermal low is gone and the cycle is ready to start again.

Over the Iberian Peninsula the thermal low can average a 4mb surface pressure drop. Over mountainous regions thermal lows can develop in summer months as well because the air over the mountains heats more than the air at the same level over the lowlands. When the Alps are under the influence of high pressure an average 3mb pressure drop over the course of a day can be attributed to a thermal low. In the northern Alps, the resulting northerly winds can flush you down a sunny south face in the afternoon, thus prematurely ending a great XC flight.

Sense of scale

Thermal lows are considered a mesoscale feature. Their resultant winds are strong enough to overpower local slope flows and valley winds. However, they are a fair-weather phenomenon, in contrast to their larger synoptic scale cousins that bring us bad weather. Nonetheless, it is important to note that this fair-weather phenomenon can still stir very strong afternoon winds especially when the topography encourages their acceleration. They can reach more than 50km inland and their late afternoon arrival can catch a visiting pilot off guard. When possible take time to question local pilots about the timing of their local winds.