There’s more going on at the coast than you might think. Honza Rejmanek kites into the lift at his local cliff to explain.

Most pilots would agree that beyond taking sled rides in light-wind conditions it is hard to find a flying scenario more controlled and predictable than soaring a coastal ridge. Yes and no. Yes, if you know what to look out for, and no, if you do not. Often coastal sites are flown in significant wind. It is important to appreciate that a wind that can keep you up in one spot is easily capable of slamming you down in another.

Mental Models

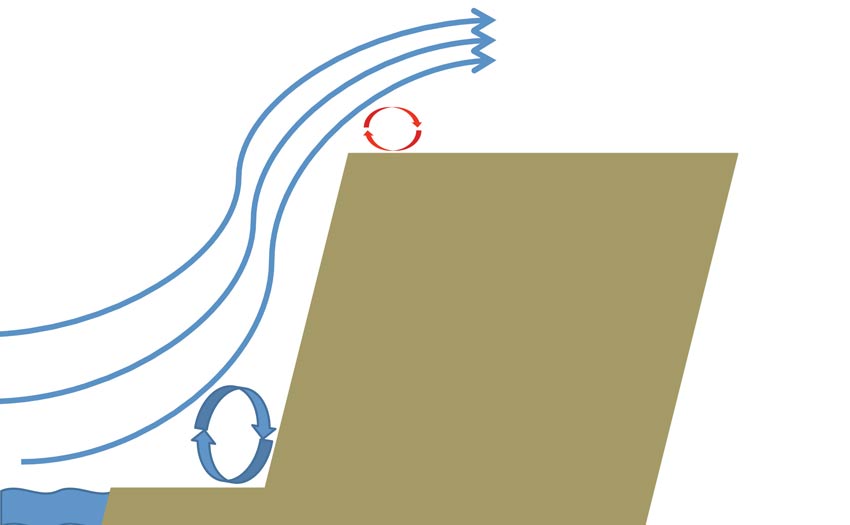

When flying under standard sea breeze soaring conditions it is important to have adequate mental models of how air behaves when it encounters steep and sharp-edged topography. Sharp edges lead to flow separation and the formation of eddies or rotors. Depending on the exact topography and wind strength these rotors will either stay localised or they will shed periodically and move downwind. Eventually they diminish as they cascade into ever-smaller rotors.

A pilot with a trained eye ought to be able to quickly see which areas to avoid based on wind direction. Sometimes only a very narrow buffer zone exists between smooth air and air that can bite. For a paraglider pilot whose wing is seven metres overhead it is often possible to fly one’s body through the strong cliff-top eddy while the glider flies in smooth laminar flow just above. This is why an inadvertent top landing on a flat-topped cliff can lead to a very tricky re-launch scenario.

Flying Cliffs

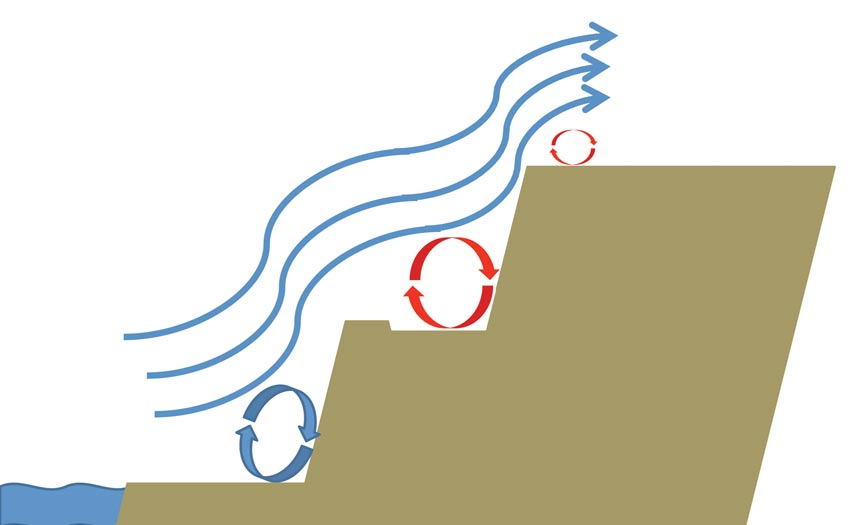

For a cliff that has multiple tiers it is important to try and imagine how the air will attempt to smooth out these individual stairs. The air, in effect, inserts ram-air stagnation zones and long roller bearing type rotors or eddies in order to smooth out the topography. The result is that the oncoming wind does not see the physical terrain that we see. For us pilots the challenge is to develop and constantly revise a mental model of how wind impacting on a particular geographical feature will modify the flow near the feature (Fig 3 and 4).

Returning to the example of a tiered cliff it is important to develop an appreciation and respect for how high one must be above the lower tier before attempting to bench up to the higher tier. Drifting downwind in order to bench up with insufficient height could put you in a rotor that would in a best-case scenario lead to a fast, unplanned landing in sink. Drifting back with just 15 to 20 metres more altitude might have led to a smooth transition into the lift band of the upper tier.

Figure 2: And when the wind is straight on. Once no-go zones are now soarable while the rotor zone behind the stack has shifted.

White Caps and Crosswind

Much of the same reasoning can be applied when looking at a coastal ridge from a bird’s eye perspective. For example, consider the knife-edge feature of eroding cliffs that protrude into the sea. When lined up into the wind such features can be fairly benign, but in a crosswind they can set up a deadly rotor.(Fig 1 and 2). This needs to be kept in mind when soaring in a crosswind. You can cross such rotors on the downwind leg with sufficient height but these rotors can create an impassable barrier when attempting to return on an upwind leg. At best this might result in a long walk back.

It could be argued that soaring the coast is a controlled scenario based on the fact that generally the wind tends to establish and diminish progressively and usually maintains a steady speed and direction. An increase in wind speed makes itself apparent on the water as increasing whitecaps, especially if the water is already rough. Gusty wind will be apparent as patches of ruffled, darker, and more textured water. These patches will be apparent as they move along the surface.

In contrast to a land surface the sea, or any large body of water, reveals a wealth of information about the approaching wind. Some clues are site specific. On certain coastlines where the coastal topography protrudes beyond the top of the marine boundary layer it is possible to see whitecaps a kilometre or so out to sea and yet the strong wind might not reach the shore all day. In such cases the wind out at sea tends to have a significant cross-shore component.

Flying Coastal Wind Shear

A similar looking scenario but with topography that does not block the entire marine layer, might be indicative of a strong vertical wind shear. The wind at the ridge is light, or just borderline soarable at best, yet a kilometre out to sea a line of whitecaps might be apparent and the wind above could be strong as well. It is as if a wedge of air has been rammed against the shore and is in effect acting like an invisible hill that is being felt by the wind further out at sea. Soaring the face of this invisible hill is a rare coastal treat that presents itself to those who happen to be around often enough or lucky enough to catch it.

Flying a coastal shear requires vigilance of its evolution in order to keep suitable landings in glide if you do decide to come down. At tropical coastal sites it is not a bad idea to also monitor what is happening inland or downwind. A growing thunderstorm can rapidly accelerate a standard sea breeze. A gust front can locally reverse a sea breeze in less than a minute. Though it is clear out to sea the cumulonimbus inland is still a fully respect-deserving cumulonimbus.

Eventually this all becomes second nature, but if you are unsure at a new site it is best to consult local experienced pilots. It is not always necessary to feel every rotor out for yourself.

Meteorologist Honza Rejmanek has been a paraglider pilot since 1993. He has competed in five Red Bull X-Alps, and came third in 2009. He has a column in every issue of Cross Country Magazine.

[promobox]