By Davor Jardas

As pilots, getting sucked inside a towering cumulonimbus cloud is one our deepest fears. Even parachutists have been known to be swallowed whole and frozen to death inside these beasts. In 1997, Croatian pilot Davor Jardas had a very lucky escape. Here he tells his tale…

Saturday, July 26th. I had a feeling I shouldn’t fly that day. My friend Matko and I woke up at 6 o’clock, packed our stuff in a rush, took a shower and headed for Buzet, the site for the competition. The weather didn’t look good. We drove through showers, and the car thermometer gave an outside temperature of 16 C – very low for the time of year.

This was the first official Croatian paragliding competition. The crew was already there when we pulled up: Boris, Kruno, Karlo, Danko, Bozo, Radovan, Srecko, Leo, Zlatibor, Joza and Sandi. We hardly get together, so we had a cup of coffee and a natter. I was on the organisation committee. We all agreed to move to launch sometime before noon. I followed Karlo by car, as we were approaching Raspadalica launch.

This was my first time there. The place faces South, 560m ASL, wide enough to allow for four wings in parallel, but relatively short and steep with a railway line just 100m below. It was hot, about 27C, and 2/8 of the sky was covered by nice cumuli. We agreed on the task and made a briefing for pilots. Air start was supposed to be at 14:30 and the marker had to be mounted on a meadow below the railway. The first turnpoint was at Crnica church, west from the start, then the church St. Thomas in the on east, then the big crossing south in Buzet, then again church Crnica. The goal field was just NW from Buzet. I moved a little away from the crowd, to concentrate and relax, imagining an ideal take-off and great flight conditions calming. If I had been alone, I surely would not fly that day. It is hard to explain but some intuitive alarm within myself turned on. But I was the president of the biggest and the most active Croatian club and my ego would have fallen apart if I refused to fly with no reason.

Leo was first off, then Danko. I dressed myself in shorts, a fresh T-shirt, a white cotton shirt and a thin windstopper jacket. I mounted my Aircotec Top Navigator on my left leg, adjusted and checked the handheld radio frequency. I also checked my reserve. Just in case I might need it. I launched at 14:05 straight into a good one. After the first climb, I read my Top Navigator’s wind information: W-SW, 16km/h. We were flying along the ridge, with some thermals apart from the wind. Although it was hot, I took my gloves from the side pocket and put them on. We surfed the ridge until 14:25, five minutes before the supposed starting marker. To the east we could see the beautiful mountain of Ucka, near which lay a big cu-nim, pouring rain. That shouldn’t bother us, I thought, as it was over 20km away and downwind.

Ten minutes before the air start, I gained some decent altitude. Nice, constant thermals, from 0.5 to 3m/s. At 14:25, Danko, my instructor, had a radio briefing with the ground support crew, and after a short conversation the decision was made to cancel the task. The reason was the overdevelopment that was observed a few kilometres north of our position, over the Mt Zbevnica (1,014 m). A radio message followed: the competition is cancelled, please aim towards landing. It sounded calm – no rush, no panic – so I took my time, and headed off to the south towards the sun and white puffy clouds, unconcerned about the black monster that was looming from the north. A big mistake.

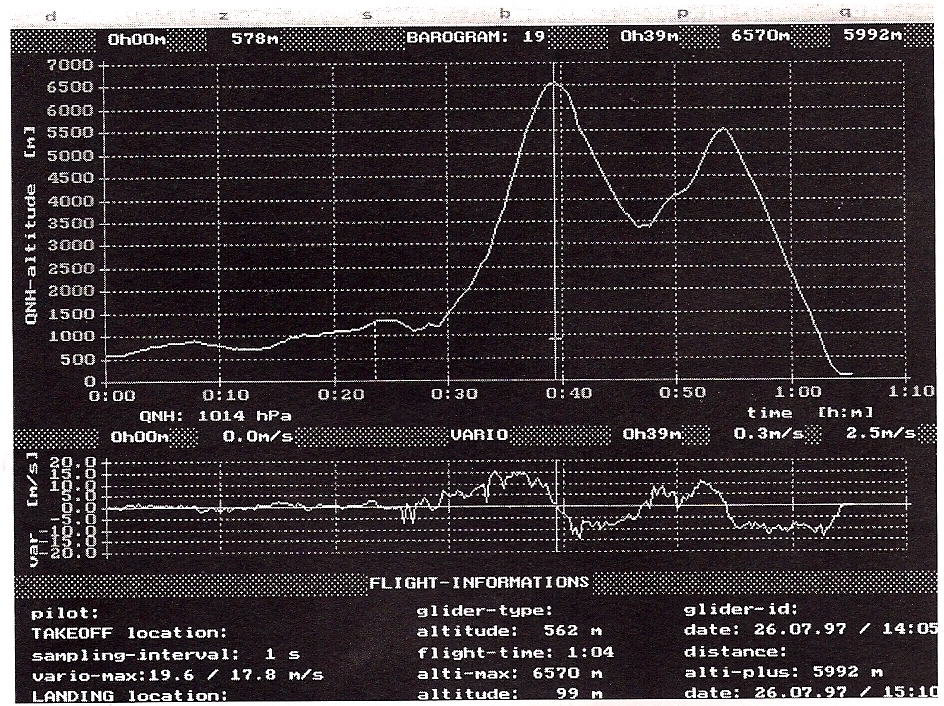

Leo was about 150m SW and 50m above me. I noticed Danko and Karlo to the W and above, maintaining big ears. Others were somewhere behind, to the N and NE directions. I was at 1,300m and decided for my first B-stall at 14:30. I was descending at -7m/s until I reached 1,000 m. Then the B-stall deformed into a rosette, like with a frontal, tips forward. I didn’t like it, it looked scary. So I released the B-stall, re-inflating and stabilising the wing and then repeated the B-stall again. After a few minutes, I looked at my vario to see to my amazement that I was ascending at 2m/s. I looked up to see Leo get sucked into the cloud, where the cloud base had lowered to 1,300m. Before he entered he took a picture of me. A couple of seconds later, holding the B-stall and ascending at 5m/s, I pierced the cloud’s base and my world went white.

At this point I’m perfectly calm. I’m very close to the edge of the cloud and I have my Top Navigator with its GPS compass function. Aiming towards the south and getting out of the cloud shouldn’t be a big deal, but I start losing valuable time, pissing about with my compass and speed bar. Navigating by the compass alone is not easy. Because of the compass’ delay I find myself steering south and actually going north. I can’t believe my eyes. Then the vario needle goes crazy. It is fluttering at 10m/s.

With no fear I pull a full frontal collapse for the first time in my life, as the dark fiend’s grip on me tightens. But even with the whole leading edge folded, my ascent rate remains unchanged. My mind spells it out: Davor, you’ve entered a cumulonimbus. I’d read many accident reports before, but now can’t remember a single one where the outcome was of survival. It gets cold, very cold. Moisture condenses on my clothes, and then it’s raining, and the water freezes over my summer clothes.

The radio is sheer panic, calling out; “Davor, where are you? Radovan, please reply…”

A desperate voice shouts advice: “Davor, avoid throwing your reserve at all costs!”

It’s ten minutes since I entered this monster and my altitude is almost 2,600 m.

I am in a strange state of mind: calm, and relaxed. I don’t care about the radio panic nor advice which seems irrelevant. Instead, my mind is fully occupied with a single thought: I have to warm up. I have to protect myself from the wind and rain and ice, wrap myself up in something, or else I will freeze.

I release the frontal collapse and decide to deploy my reserve so I can pull in my paraglider and wrap it around me for some shelter. As I release, the vario goes crazy, peaking at 18m/s. I tug my left A-riser, the lines go slack, and I enter a spiral. I wrench at my reserve handle on my right side, lobbing it away into the dark gloom.

Then horror, pure fear: the reserve hangs limp, undeployed at the end of its lines, and my main canopy is out of control, cravatted on the left side. I’m still climbing at a horrendous speed, and so it takes ages for the reserve to deploy. Seconds later I hear a muffled crack and see it open and overtake my glider. Thank God! With a burst of adrenaline-induced energy, I haul in the main canopy arm over fist and wrap its damp nylon around my shivering bare legs.

I radio to say I am alive, at 4,500 m, under reserve parachute and still going up at 10m/s. That was my last radio call. Boris told me later he was horrified with the unrelenting scream of the vario, contrasting with my voice, which was gentle.

The radio yells back, “Where is Davor. Davor, call us back!”

My dear friends, I think, I cannot call you now, because I need to preserve every particle of energy, which could make the difference between life and death.

I remember an accident report about a twisted parachute during a longer descent. But looking up, my Czech-made Sky Systems 32-metre reserve is stable and tense. In a few seconds I establish a relationship of trust with it. Hailstones batter me, hitting from all directions, drumming on my helmet, harness and wing. The vario is wailing out an impossible tone, but I cannot look at it in case the numbers make me faint. I am now being thrashed in all possible directions.

Lightning flashes surround me, bursting the dull greyness to the left, right, below and above. Every few seconds a dimmed flash of light is closely followed by a thunderous explosion. How far away was that one? If hit by a bolt, I’d be fried in a second. Davor, chances that you will survive this are zero, pure zero, accept it as a fact. In my foetal position I desperately pray to God to save my life. Would there be many people at the funeral? The easiest death would be to faint from hypoxia, then fall into my reserve and fall, smashing hard into the ground. My father, who lives close by Rijeka… does he know that I am here, above him, his only son, and that these are my last moments?

Then something else crosses my mind: Davor, what kind of thoughts are these, you must not give up, you are still alive, have you done everything you can to protect yourself? A quick look at the vario tells me that I am at 6,000m! At that altitude, I will either faint due to the lack of oxygen, or freeze. I consciously start to breathe faster, to hyperventilate, in order to avoid fainting without oxygen. The air starts to get terribly cold. I’m in shorts at nearly 20,000ft, with the wind blowing fiercely. I’m freezing. No, I can’t afford to feel cold! I remember my friend Kalman. He was caught in an avalanche in the Himalayas, at Pisang peak, and he survived with an open leg fracture. He had an enormous desire to live: he could not afford freezing, especially not giving up! Davor, I forbid you the luxury of feeling cold, you can’t afford it now!

How high will I go? For how long? Where am I? When and where will I fall from the cloud? I calm down again. I think, right, now it is all about those tiny little things that can mean the difference between life and death. While you are still conscious and OK, what can you do for yourself? Are you well wrapped in the canopy? I free my right hand, pulling the canopy from my back, trying to wrap it around me as well, using my last molecules of energy: I feel weak. If I pass out, it is important not to suffocate. I shift my head to hang down on my chest so I should be able to breathe even if I’m unconscious. Then, it would be important that I don’t freeze, so I check that the canopy is well wrapped and secured around me. I pretend I fainted for a moment, letting my hands loose, and it seemed OK. Would the paraglider canopy entangle with the spare?

The cu-nim pulls me higher, to 6,500m, at a speed of 20m/s. The cold is unbearable. The worst of it is the icy wind blowing between my back and the harness, where I’m not protected. My leg straps cut into my groin, sending stabs of pain through me, but it is nothing compared to everything else. The reserve is rotating and jerking all around me. I don’t know if it’s above or below me. Frankly, I don’t care.

Then I start to descend, from -3 to -17m/s, until I reach 3,300 m, then I lift up again, up to 5,500 m, then down again. Suddenly I see something. Earth. I cannot believe my eyes. My hopes rise, maybe I’ll survive. Earth, Mother Earth, it exists, it is here, I am looking at her, I am travelling towards her. A beautiful lake, forests, nature. Hail falls almost horizontally, melting, warming up and transforming into big raindrops. But the reserve is bucking and spinning out of control.

It’s a whole new situation. I’m now fully focused on the next trauma: landing. I try to get rid of the main canopy wrapped around me, to release it partially so that it’ll lend some resistance to slow my descent, but I am too wrapped up. The scene worsens: I am flying towards power lines and a burnt forest with sharp, naked branches pointing to all directions. Oh, no! After all I went through, would I end up finished on power lines or nailed to a spear-like branch?

Davor, don’t be unthankful for the miracle that allowed you to exit the cumulonimbus without injuries! In my mind, I think about landing and PLF-ing. I’m really shifting over the ground, like I’m driving on a highway. I stretch, trying to put my legs together, preparing to roll on landing. I pass a few metres above the power lines and hit a tree with my air bag, which absorbs the smash. I stand on my feet, frozen, wet, scared, shocked, but still, alive, completely uninjured! It seems impossible! I am shaking from the cold. It’s raining cats and dogs. I look at the figures on my Top Nav instrument, and see that I’ve travelled 21km from where I entered the cloud.

I hike out to the road and stand in the middle, trying to stop cars with my thumb, but the cars just circle around me. Shaking, I continue to walk, thinking ‘Davor, you look like a forest goblin, completely soaked, with a rucksack on your head, covered in leaves and with a bunch of nylon in your hands. Who would be crazy enough to let you in their car?’

I’m relaxed. It’s not a matter of life or death anymore. Soon I come across the village of Säusönjevica. Civilisation, people! I pass the nearby graveyard, approaching a new house. There are signs of life: a kid’s bike, a car, tools and stuff around. I haul my lazy body up the stairs to the first floor, ring the bell and knock on the door. A man appears. I can’t stop my flood of emotion; “Please excuse me, I was flying with my paraglider and got sucked into the storm cloud, I am cold and in shock, can I call my friends from here, please help me…”

Branko Rabar welcomes me into his home. A great man. I give him the organisation’s number. His wife wraps me up in a blanket to get warm. I tell them, “It’s a real miracle I am here talking to you….” I take a shower and the warm water soaks away all the dirt, sweat, fear and shock. We drink tea on the balcony where the sun is shining, the sky is crystal blue and there’s no trace of the thunder cloud which I had battled with all afternoon. By 4:00 pm, only an hour and a half since I entered the cu-nimb, a totally new day had begun.

THE OTHERS…

My instructor Danko went through a couple of negative spins resolved by a full-stall, after which he landed on a meadow. Karlo entered a negative near the ground, threw his reserve at about 30m which barely opened. He landed uninjured as his canopy hit the power distribution pylon and ripped, taking his weight. Srecko pulled all the risers on one side, a new manoeuvre in paragliding. The wing entered a steep spiral, which he held for about 20 minutes, keeping just below cloudbase. He could not feel his arms for days later. Radovan pulled big ears, leaving only a few cells open. He still went up at 10m/s but was eventually spat out by the cumulonimbus. Seriously disorientated, he couldn’t recover his glider in time and hit the ground hard, suffering serious bruising and a twisted ankle but incredibly nothing worse.

Kruno did a full-stall, but when he released, his glider surged and cravatted, so he threw his reserve. He was spared by the thunder cloud but he couldn’t pull in his main canopy, and he hit the ground hard, crushing his vertebrae but with no severe consequences. Leo was given the same horrific treatment by the thunder cloud as I. He didn’t throw his reserve (he was dressed in a skiing jacket), but maintained a full frontal deflation by inserting his legs in his A-risers and pulling down. He was thrashed into a forest near Ucka.

Altogether, seven candles could have burned, but all of us survived. During the evening, we settled in at the private hotel, and I invited everyone for dinner to celebrate our new life. We went to a restaurant with a symbolic name: Fortuna. After dinner I went to bed. I thanked God for saving my life and fell asleep, completely exhausted.