How to take care of your paraglider

Paragliding industry insider Till Gottbrath has seen it all when it comes to paraglider care. Here’s his in-depth guide to taking care of your wing

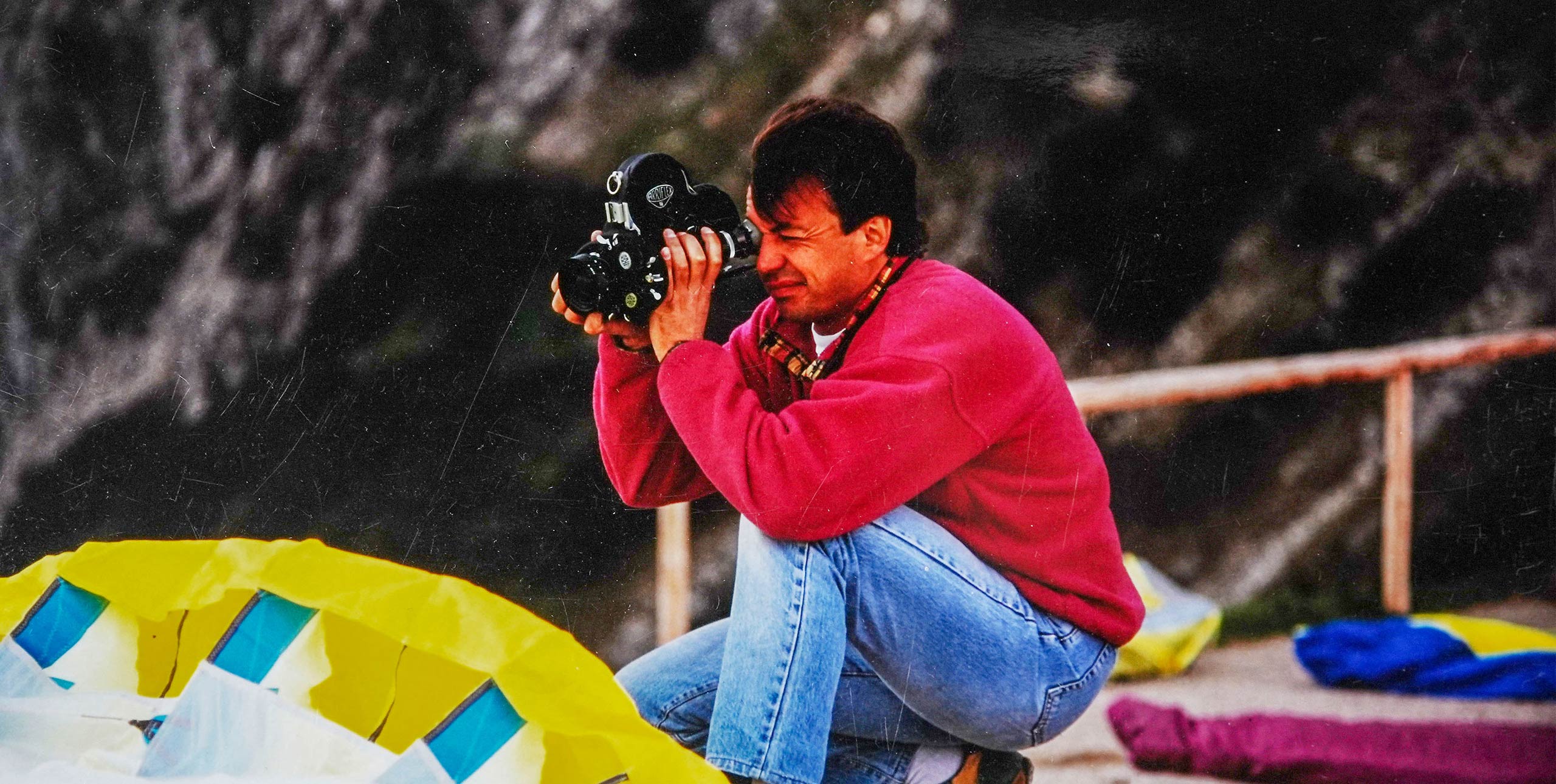

15 January, 2022, by Till GottbrathIndustry insider Till Gottbrath has seen it all when it comes to glider care. Here’s his in-depth guide to taking care of your wing

How long your paraglider lasts depends how your treat it. At Nova’s service centre in Austria we sometimes get gliders in for checking that have 500, 800 or even more operating hours that are still in good shape. Others look very worn after only 150 hours or less. It’s not just time in the air that counts: operating hours include air time, groundhandling or any time the wing is unfolded and exposed to the sun. Here’s how you can help your glider last longer.

Sand, dust and salt

Sand, dust and salt are made from very fine particles that can be hard and have sharp edges. They primarily attack the coating of the cloth. They literally rub it off and this increases the porosity of the wing. The operational life of the cloth is reduced and the susceptibility to deep stall increases.

Additionally, the diagonal elasticity of the fabric also increases. What does this mean? Fabric consists of warp and weft threads, so it is basically dimensionally stable in these two directions: diagonal to warp and weft. However, a fabric always has a certain elasticity – and this is anything but desirable in terms of aerodynamics. Since the coating “fixes” the warp and weft threads as it were, worn wings can no longer maintain their shape as they did previously. In extreme cases they develop actual bulges.

Salt, sand and dust not only shorten the operational life of your glider, they also reduce its safety and performance. The really bad thing about sand and dust is that it is nearly impossible to remove it from the wing. You may be able to get rid of coarser grains of sand if you hang up your glider with the leading edge downwards and try to brush and shake the grains out of every corner, but it is impossible to remove every last grain. So it’s better to try to avoid the wing coming into contact with sand and dust in the first place.

Dampness

Wet textiles start to smell and mildew stains can form. Anyone who has ever packed up a wet tent and forgot about it knows this. What also happens is a hydrolysis process that attacks the coating. Damp + heat + time are an unhealthy mix for PU coatings.

A wing that is packed wet and is left in the boot of a car in the summer sun may well be affected. Never store a damp wing for a long time. Wet or damp wings should be treated with care and hung up to dry as soon as possible.

Sunlight damage

Light consists of a visible and invisible spectrum, UV light. UV light is in the most energetic in the spectrum. UV damage can affect human skin, so it can certainly affect paragliders. After a while the fabric bleaches, but it also becomes more prone to wear and tear. If the cloth feels smooth as soap to begin with, when it ages it feels like parchment.

In recent years cloth manufacturers like Porcher and Dominico have worked hard on continuously improving their fabric’s UV resistance. The polymer polyamide 6.6 (the generic name for the brand name nylon) is no friend of the sun. The UV stability of pure polyamide 6.6 is insufficient for outdoor use. This means that fabrics made from polyamide 6.6 fibres have to be coated with UV protection. As described above, this coating can be weakened by unwanted external influences.

For longterm joy with your wing, don’t leave it lying around outside longer than is strictly necessary – even in shade or under overcast skies. Even then it is exposed to UV-rays.

UV-rays present no problems for your lines. Dyneema is generally very UV resistant. Aramid (brand names Kevlar or Twaron) on the other hand is very UV sensitive. But don’t worry – the coating of unsheathed Kevlar lines or the sheath offers enough protection that using them for 1,000 hours is no problem. However, in wings that are ten years old or more the strength does deteriorate. In this case you should have the glider professionally checked before flying it.

Salt crystals

Salt crystals not only attack the fabric (similar to sand and dust), but also the lines. When checking the line strength, lines break just above the maillons, especially in wings used for instruction. Why? Firstly, the lines are often bent and secondly, salt crystals scour this area. Salt is not just from the sea: if you groundhandle without gloves salt crystals will form from dried sweat. Tip: use cycling gloves.

Crazing

Paraglider cloth always has a coating, usually polyurethane and/or silicone, sometimes only on one surface and sometimes on both, and of different thickness (depending on the application, eg double-sided and thicker for the cell walls). The coating makes the cloth (more) impermeable to air, increases UV resistance thanks to so-called stabilisers and fixes the warp and weft threads.

In the course of time, creases may appear white in the coating: this is crazing. These occur because the cloth is folded very tightly. This is more noticeable in sail cloth that is made from dark colours with a thicker coating. Crazing is hardly noticeable on white or very light coloured cloth. Crazing is also not noticeable if the fabric coated on one side is sewn in such a way that the coated side faces inwards.

Crazing cannot be completely avoided in the long run – regardless of which fabric and from which manufacturer. But if you rarely pack your glider super tight and do not keep it that way, you can prevent or delay the phenomenon. Crazing is not a real reason for worry – cloth with crazing may look ugly, but it has no adverse effect on the airworthiness of the wing. Other factors limit the operational life of the glider much sooner.

Frayed brake lines

In some lightweight wings we use ceramic rings to route the brake lines. For some pilots these low-friction rings cause no problems throughout the entire operational life of the paraglider. With other pilots, over time these rings develop sharp edges and fray the brake lines or in the worst cases, even break them.

Why? It isn’t the fault of the rings, but the cause is the sand, dust and salt crystals on the lines. These sharp-edged particles initially act like sandpaper on the extremely robust ceramic coating of the ring. If the coating is worn off, the ring gets an edge and this frays the brake line.

Thankfully this phenomenon occurs in a minuscule number of gliders (one in a thousand wings are affected), which is why we keep using the rings with confidence. We deliberately only use low-friction rings in lightweight wings. In flying areas where there is a lot of sand and dust we don’t recommend flying light wings.

Additionally, the direction of pull on the brake lines should be parallel to the risers. Spreading your arms wide is an aerodynamic no-no and also causes the brake lines to fray, regardless whether the glider features rings or pulleys.

Leading edge damage

Sometimes we get wings for repair where the cloth on the leading edge is worn or worn through. The most likely reason for this (even if the pilot denies it) is that after landing they bunched up the glider and walked over tracks, stony paths or asphalt to an area where they could pack it. During this walk the glider was dragged on the ground.

Because most gliders now feature nylon rods in the leading edge, a hard surface is scouring on a hard surface – and in between is the soft fabric. The damage is as marked as it is obvious. Unfortunately the repair is difficult and therefore expensive. Fortunately, this type of damage can be easily avoided. Always carry your wing so that it never has any contact with the ground. It’s that simple.

Similar damage can occur if you fully lay out your wing on a hard surface when packing it. The seams in the upper surface and cell walls are so stiff that they are also potential wear areas. To help reduce damage when packing on a hard surface, choose a different packing method, like folding it from a mushroom.

Keep it loose

Life would be perfect if you could store your glider at zero gravity, in a dry, completely dark, well-ventilated, temperature controlled room. Sadly, nobody has that option. But you can try to re-create those conditions as best you can. If you can’t recreate weightlessness, you can at least minimise factors like dampness, tight packing, UV damage, poor ventilation and high temperatures. Don’t keep it in the boot of your car in high temperatures.

Removing stains

A dirty wing not only looks ugly, but in the worst case the dirt can harm the fabric or its coating. Try to protect your wing from aggressive acids as well as silage, cow pats, grease, oil, etc. If you do get stains on your wing, first try to remove them with a soft sponge and lukewarm water – immediately if you can, rather than three weeks later. For more stubborn stains, you can try very diluted soapy water. If in doubt, contact your dealer or the manufacturer for advice.

Till Gottbrath has worked in the outdoor industry his whole career and works for Nova in communications. He has been flying since the late 1980s and considers himself a “passionate gear geek”. As well as flying he loves trekking, hiking, biking and skiing. He founded the Nova Pilots Team in 2006 and Nova Juniors Team in 2009, and now manages both. A version of this article first appeared in 30 Years of Airtime, published by Nova and available to download at tinyurl.com/30-years-airtime