Which flight instrument is right for you? In-depth review

11 November, 2015, by Hugh Miller and Marcus KingDazzled by which flight instrument to buy? Hugh Miller and Marcus King look at the different needs for different pilots and round up the kit, from basic buzzers to competition varios and GPSs

The soaring pilot

If you’re starting out, your priority should be learning your core flying skills. Instruments should be simple and easy to use.

Naviter’s Andrej Kolar says, “Any instrumentation you use shouldn’t distract you from flying the wing. Getting used to the wing and how it reacts in turbulent air is the priority.”

An audio-only vario is perfect – it allows you to get a feel for what the air is doing without having to be constantly looking at a screen. Unless you are flying a hill that sits under airspace, you shouldn’t need to worry about your altitude, and you’ll start building a feel for how far you can glide.

Many pilots – including Bruce Goldsmith – suggest you learn to thermal without any instruments at all. “Ditching the vario enables you to concentrate on searching for better lift rather than getting your senses flooded by what lift you just flew through,” he explains.

Learning the way the glider moves as you approach a thermal will help you predict where the thermals are in relation to your wing. Once in the thermal you can monitor your progress by referencing your height to a feature on the hill such as a rock or a tree. Use your senses to feel the acceleration and observe how other pilots and birds etc are performing in comparison to you so you can build a picture of where the rising air is strongest.

Getting up and away

Altitude, speed and heading information all now come in useful – but don’t rush off for a full-spec instrument just yet. It’ll only confuse things.

In terms of avoiding airspace, we recommend QNE altitude and GPS altitude.

QNE is the legal altitude, but GPS is still used by some cross-country leagues. You might think this is a bit old school, but we’d advise against flying with a complex moving map airspace display at this stage.

It’s a bit like learning a new driving route: it’ll go in much better if you do it all manually rather than just plugging in the Sat Nav. Get the maps out and plan your potential flights long into the evening before the big day. Knowing where you’re headed in advance makes it all much less daunting. Go for areas clear of airspace so you can focus on skills like finding the second and third climbs, and understanding how thermals drift and form.

You’ll come to look at your speed indicator as much as your vario averager. Speed increases as you get pulled towards a climb. Most instruments give fairly basic wind speed and direction information, because they don’t know your airspeed – so take this with a pinch of salt.

During these initial adventures you should also learn to read an airspace map – many countries still require you to carry a paper map by law.

Nearly all instruments log flights as IGC files, so you can upload to your league, compare your flight with those of others, or replay it on Google Earth or Doarama, but a word of caution – some leagues don’t accept XCSoar tracks.

The regular XC pilot

It’s time for a moving map airspace display. Many pilots add on a second instrument – a smartphone, tablet or Kobo to display this type of information. A big screen, preferably on a second unit, is ideal – you want the map to be clear and instantly visible. Some flight computers like the Compass and Oudie 3 have fully graphical screens, and nearly all give warnings when you’re getting close to prohibited areas.

World Cup pilot Adrian Thomas says, “I like to have an audio warning that tells me when I am going to hit airspace if I keep going in the same direction, or climbing at the same rate for some time.

“I also need a good snail trail to show me that I am clear of airspace as I go round it. These airspace avoidance aids are particularly useful when you start to fly XC beyond your familiar area.”

Look for a big display which you can easily zoom in and out of so you can have an overview of what airspace is coming up, and can get in close if you’re up tight against a prohibited area. Consider having two computers, each with different scales, if you fly in really busy skies.

You might also think about getting FLARM integration if you regularly fly in areas with lots of sailplane pilots whizzing about. This system alerts pilots of potential collisions.

Live tracking will be useful if you are heading off into the wilds. Some instruments have GSM technology built in, while others make use of Bluetooth or WiFi connections to your phone to send the data to servers on the internet – the advantage being that no extra data SIM is needed. Some flight software, like FlySkyHi, will display the position of your flying buddies on screen as you are flying, making it easier to keep track of each other.

However for much better safety, fly with a satellite based tracker like a Spot or an EPIRB emergency transponder: these don’t rely on mobile phone signal.

The hopeless XC addict

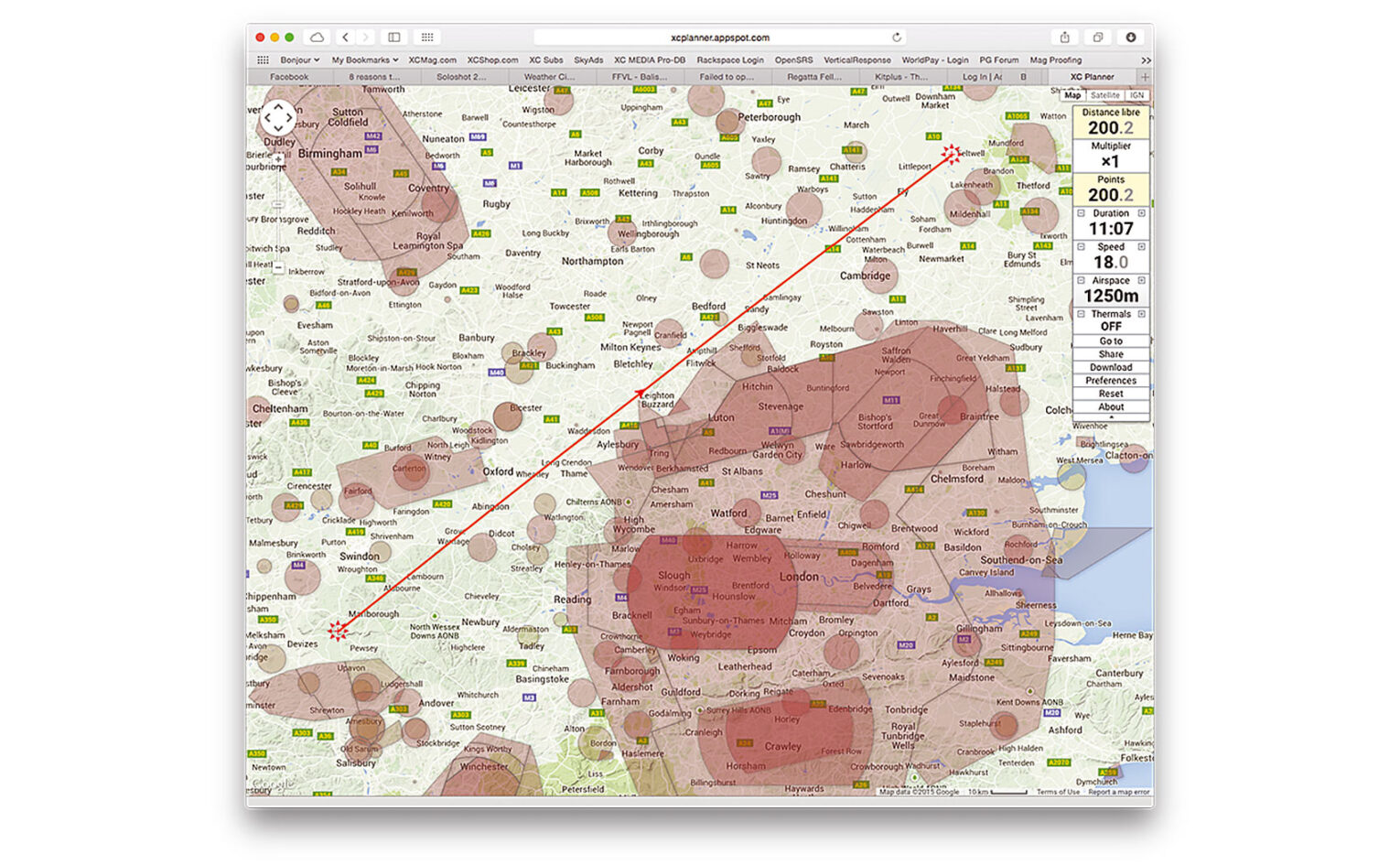

As you get more into your XC flying, you might start wanting to attempt defined flights – triangles, out and returns or your own goal tasks. Set your route using software such as XC Planner or SeeYou (in the App Store or Google Play).

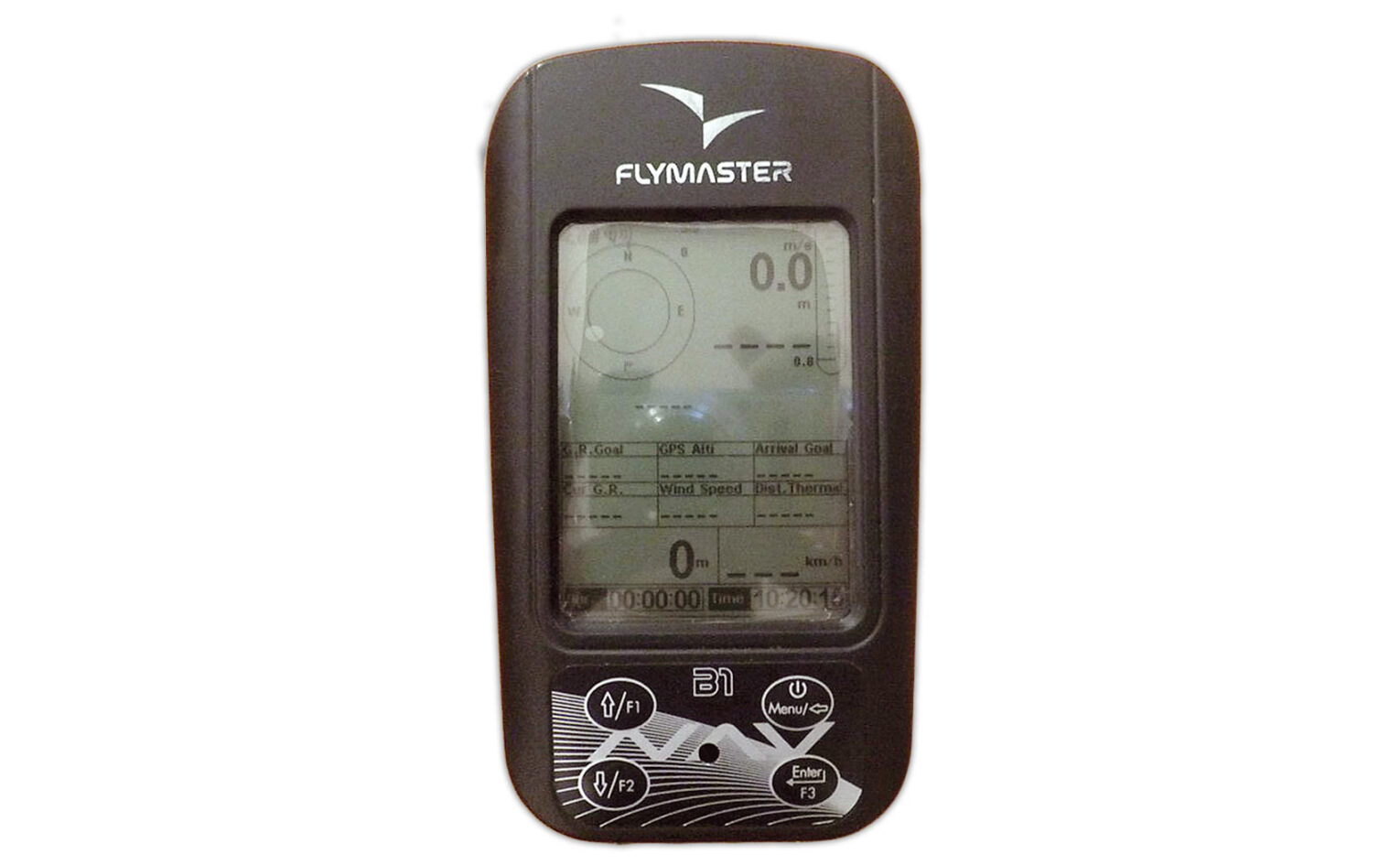

Once you’ve set your route, you can download the turnpoints to your instrument and set the task. When you then fly the task the IGC log needs to include the turnpoint declarations. These are known as C records, and not all instruments support them – for instance with Flymaster, the older B1-Nav doesn’t, whereas the Live does.

As we all know, conditions on launch aren’t always those that were forecast. Some instruments make it really easy to set a task on the hill, like the Oudie 3. You set your task or goal simply by drawing it on the screen.

Some instruments also give you an optimised FAI-triangle display, so that while you’re flying, it’ll show you how to get into sector to maximise your points. This is perfect for flying ad hoc, going wherever the conditions look best, or if you have had to abandon a previously planned route because of a change in conditions.

The top Alpine pilots now use software that gives them up-to-date weather along their declared task, helping them to decide whether they should continue or deviate to a new task. We can expect more and more of this ‘live’ data being displayed on instruments.

Glide angle is a really important consideration – ‘Glide Ratio Made Good’ is most useful. “I always look at the glide angle required round all the turnpoints and into goal, and current achieved glide,” says Adrian Thomas. “I fly speed-to-fly round the course – going full speed unless the climbs are weak, the turbulence is extreme or there are lifty lines. I start thinking about the final glide from about half way round the course, comparing glide required to goal with currently achieved glide.

“Most instruments will also give you an audible warning when you climb to a height where they think you can make it in, and I set those to go at 10:1. I generally make it in with significant height if I go when the alarm goes. Once I go for goal I constantly compare required and achieved glides.”

Competition guns

It’s stressful on launch: the last thing you need is a complicated instrument you’re unfamiliar with. Calm your nerves with a reliable, rock-solid instrument that you can easily programme and use to navigate round the task (even with slightly shaky fingers…).

When you turn up and register for your first comp, the organisers will usually squirt the turnpoints straight to your instrument – but you should still know how to input one manually as occasionally a meet director will want to use an unexpected turnpoint. You should also make sure you understand the different types of cylinders, start gates, speed sections and goal definitions and how they are input into your specific instrument.

At task briefing, some organisers can automatically send the task to instruments that are connected to the internet. If not you’ll be plugging it in yourself. But when you’re checking the task you have input, it is useful to see a task overview in graphical form. Does it look like the one on the taskboard, and do the total and optimised distances agree?

It’s also vital that your instrument displays all the information you need clearly. Before the race start it should provide a countdown to the start time, and help you decide when you should start gliding to the start line.

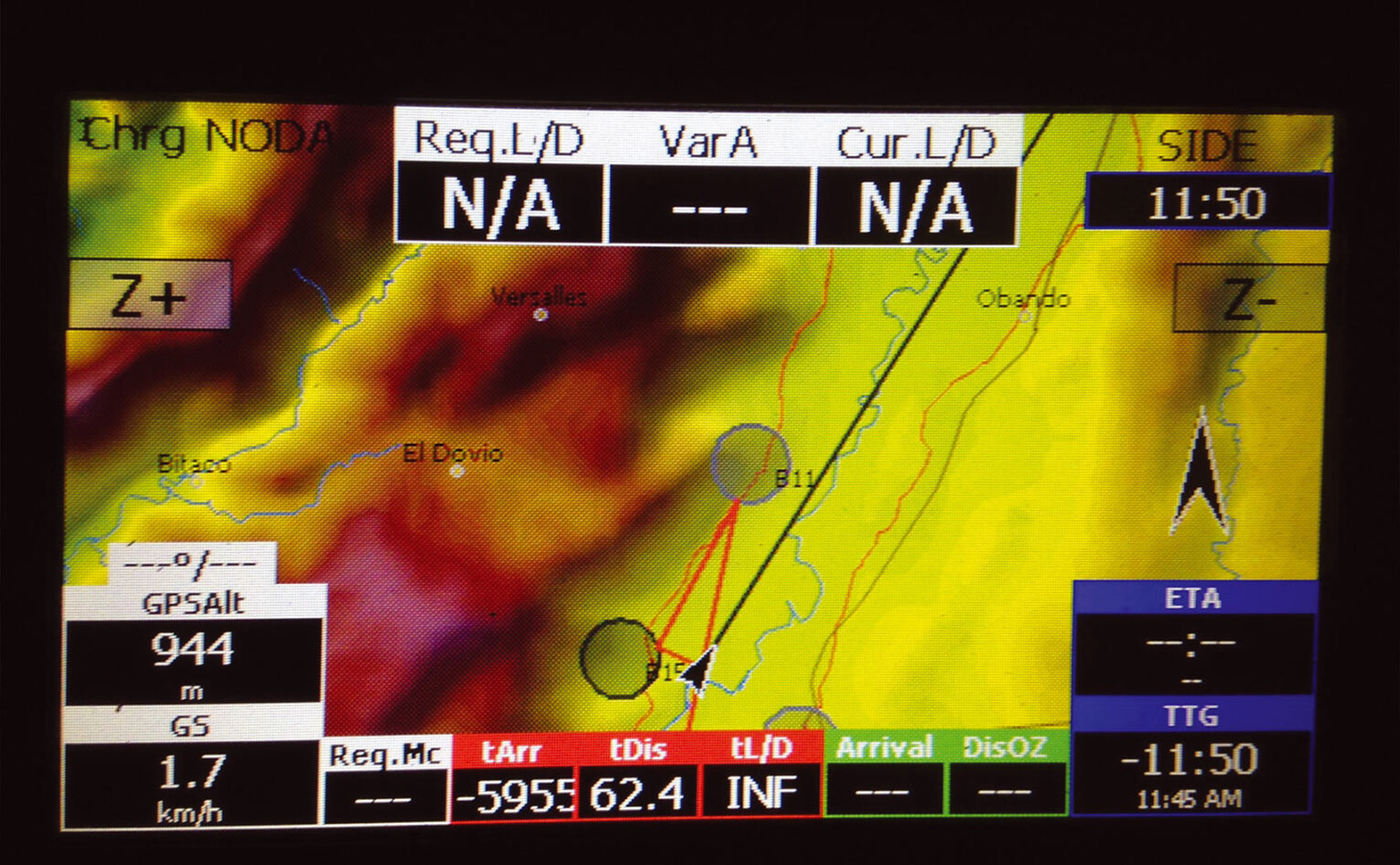

Once on task your instrument should move onto the next turnpoint once you have logged a point within the current cylinder – there’s nothing worse than button pressing with thick gloves in busy thermals. Terrain maps, as offered on computers such as the Oudie 3, XCSoar and LK8000, help you work out exactly where the cylinder edges are – really useful for task planning.

France’s Charles Cazaux agrees that a ‘no-touch’ instrument is vital in competition. “I need only one page for competing, showing: vario, barometric altitude and GPS altitude, current L/D, groundspeed, arrival height at goal, distance to goal, glide required to goal, arrival height at turnpoint, distance to turnpoint, glide required to turnpoint, automatic zoom, time to start, time before start, airspace and alarm.”

The instrument should help you fly the shortest route possible, with an overview of the remaining sections of the task. As you get close to the finish you will need information such as glide angles and wind speeds to optimise your final glide. With more and more competitions being scored directly from the live trackers you probably won’t need a backup log, but you may well want a second machine so you can complete the task in case your main instrument fails.

Paragliding coach Pat Dower says lots of climb information will improve your speed. “In great racing conditions in Colombia, I found I could make more educated decisions about when to leave or reject a climb and keep on pushing, and could stay up with the leaders. I’d recommend average climb for the thermal, average for the previous climb, average for the day and of course a 20 second average too.”

What nearly all the top pilots agree on is you must get to know your instrument well before using it in competition. Chrigel Maurer’s advice is this: “You need to know exactly what you need from your instruments and know what they do.”

Charles Cazaux recommends, “reading the manual while playing with the instrument at home or walking around. Set your navigation page with the information you are used to, then try it and redesign it if you need to. If your page is well set, you will not need to touch your instrument while flying. This is a good sign!”

Adrian Thomas suggests flying with one instrument at a time when getting used to them. “It is amazing how quickly you can get used to each instrument when you have to rely on it,” he says, “and equally amazing how long you can go without figuring it out if you don’t have to….”

Need to know

- Buy an instrument you can grow into, but keep it simple in your early days

- Always use a proper airmap and check your route on it before comparing it with your downloaded airspace file. There may be differences!

- Set your climb averager to 20 seconds. It takes most pilots 20-25 seconds to complete a circle, so this gives you the climb rate across the entire 360.

- Get an instrument that displays both GPS and barometric altitudes. The FAI has introduced barometric pressure for Cat 1 competitions. Barometric is also the ‘legal’ airspace altitude.

- External ASIs (air speed indicators) aren’t used much by paraglider pilots. They are expensive, and easily damaged. However they are the only way you’ll get properly accurate wind direction and strength information. GPS only is a little inaccurate, based only on your drift while circling, and doesn’t work at all well on glide.

Choose your instrument, Sensei warrior

Our advice is this: take your instrumentation seriously. You are flying an aircraft, after all – buy an instrument that is fit for purpose. Do not rely on a phone app or cheap GPS as your primary navigation system. Invest. “We have got to be more responsible and use dependable, solidly built instruments,” says John Stevenson of the UK league. “We need accurate instruments to navigate and show we’ve been responsible to the agencies that control airspace.”

The SkyBean

It doesn’t get much simpler than this: a small colourful audio-only vario powered by watch batteries. We found the instrument nicely sensitive and appreciated its four volume settings. With just one button, the unit has a menu system using a couple of coloured LEDs. You can alter the lift and sink thresholds to your preference. If that isn’t enough control you can remove the casing and, with an optional programmer, generate your own audio profile on their website and upload it to your instrument.

Batteries last 150 hours – we’ve done a full season with ours and it is still going. Weighing just 26g, it’s a great first vario which you’ll keep as a backup forever – or even use as your main audio vario with a Bluetooth tablet or smartphone app.

Pros: Simple to use, long long battery life, customisable audio, always with you if you keep it on your keyring, allows you to concentrate on flying

Cons: No screen, no connectivity

Tip: Use with an alti-watch for cheap alti vario

Stats: 26g, 150 hours battery, €59

Alternatives: Solario, BipBip solar vario, Compass beeper, Syride SYS’One

FlyNet XC

Don’t let its simple appearance fool you. Internally this is a fully specified alti/vario and logger. Designed to be paired with a smartphone or tablet using Bluetooth 4LE (low energy). You can use any app that supports the device such as FlySkyHy. Apps are available for both iOS and Android platforms.

Inside, the device is packed with sensors – a high quality GPS, a precise air pressure sensor which is much more sensitive than your phone’s and accelerometer. Not using your phone’s GPS will make a significant difference to its battery life, although we still recommend an external battery for long flights. As well as transmitting the data, the unit can also log the data as a standard IGC log in its internal memory with automatic start, though you can’t record C records for declared flights. You won’t need additional software to save the stored IGC file, just attach the ASI to your computer with a USB cable.

We found the vario pleasant and responsive, and the battery life good, lasting a few good flights so in line with ASI’s claims of up to 15 hours. It may seem expensive but it is undeniably accurate. If you want a backup logger and also more accurate inputs to your flying apps this is a great device.

A pared-back version also exists. The FlyNet 3 is in the same compact box but in green. It can be used as a standalone vario or paired with a smartphone and an app as a vario and accelerometer. Billed as a good backup vario it weighs only 40g and promises 30 hours of battery life. Velcro straps for both instruments are sold separately for a few euros each.

Pros: Accurate sensors, fully functioning, great for linking with a tablet, good battery life

Cons: Expensive, no C-record storing

Tip: There are now some Android tablets available with E-ink displays that will connect to the Flynet XC

Stats: 50g, 15 hours battery, €325

Alternatives: Flytec SensBox (adds high speed logging), GoFly iPico

Flytec Element

The first of the new range of instruments from Flytec, the Godfathers of free flying instrumentation. It’s a solid vario/GPS, simple enough for pilots just getting into XC and comps, with basic functions all covered and more promised in future firmware releases. It replaces the 6000 series, though the 6030 remains the instrument of choice for most comp HG pilots. The unit runs on two AA batteries – handy as you’ll never run the risk of being stranded with a vario you’ve forgotten to charge. You can also use NiMH rechargeable cells in the unit.

The front is dominated by the LCD screen with no less than seven membrane buttons with good solid clicks that we could feel through our gloves. The setup uses these buttons and there’s lots you can change. As with older units you can customise the audio sound as you want. With the new Connect One Flytec have introduced audio profiles to simplify this, and we wonder if we will see this on a future update of the Element.

You can input routes, though one bugbear we found is that the current firmware doesn’t allow uploading of waypoints from files so you’ll be doing a lot of button pressing. Promised updates include airspace warnings and optimised routes for competition. The unit currently gives direction and glide angle required to your next waypoint plus audio notification of when you have reached it. There’s also a final glide calculator.

IGC log files are easily retrieved – the Element acts as a USB drive, so you won’t need any special software. A future update promises Google Earth compatible files straight from the machine. Firmware updates are a simple case of copying a file to the machine.

Pros: Simple to use, clear screen, uses easily available batteries, big solid buttons, no special software needed

Cons: No graphical screen, some promised functions currently missing, no connectivity

Tip: Keep spare AA batteries in your flight deck

Stats: 178g, 30 hours battery life,€499

Alternatives: Flymaster GPS or NAV, Aircotec XC Trainer Easy, Digifly Air SE

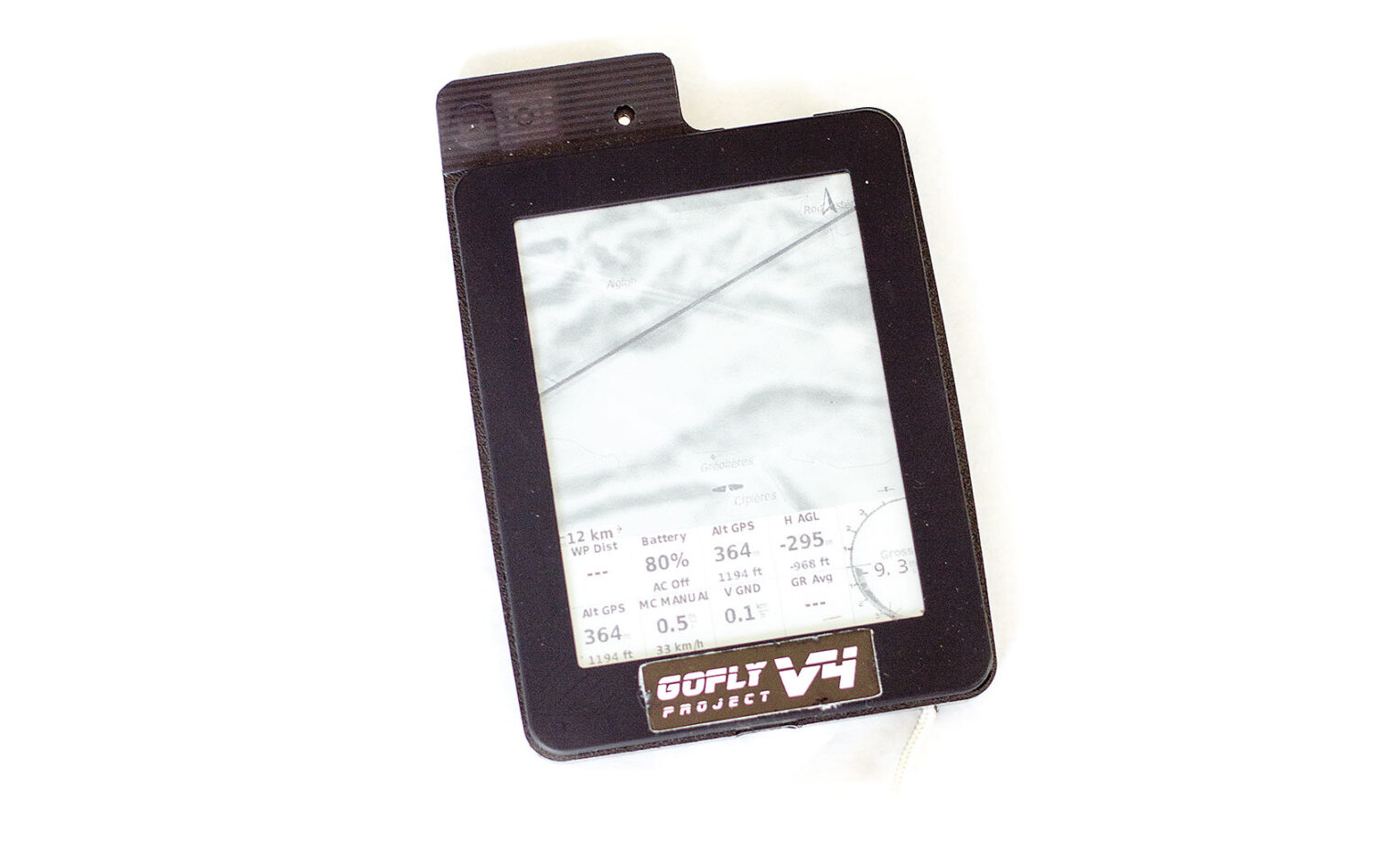

Gofly Instruments Kobo

Any practically-minded pilot will have already gone to their local shop, bought a cheap eReader, taken it apart and reinstated it as a fully fledged XCSoar flight computer. I take it that’s not you, if you’re reading this?

Here’s what you’re missing out on: a brilliant, clear moving map that’ll show you exactly where you are and where you’re headed in relation to airspace. Much like the Oudie 3 – but slightly clearer – and, well, with a few less functions. For example, no C-records are stored, making declarations with this null and void for many leagues. But as a second screen, the Kobo, for value and usability, is unmatched. Pair it to a Bluetooth-featured vario and it’s an all-singing, though not quite all-dancing, flight computer.

For those that don’t fancy getting out a soldering iron GoFly Instruments will supply a ready hacked version. In the mail you’ll get a Kobo with everything fitted: GPS/vario board, the Pico Insider, as well as a custom back for the unit that holds the chips and an extra battery which triples the battery capacity giving up to 20 hours of battery life. The instrument we were sent also has a Bluetooth module so the GPS and vario data can be transmitted to your phone or tablet for use by a flying app, and it worked seamlessly in our tests with FlySkyHy. XCSoar, the software the units run, is a fully fledged soaring app.

The great advantage is the e-ink display, designed to be readable in full sunlight. There can be some ghosting if lots of things are moving on screen, but usually the display is clear. There are questions about how long the screens will last as they have a limited number of writes, and they are supposed not to be able to cope with cold temperatures – although we’ve not heard of any real issues.

Pros: Clearest display we’ve ever used, easy to zoom in and out (just swipe), cheap and simple if used just for navigating airspace, triangle calculator and many XCSoar features

Cons: No C-record, can be fragile.

Tip: download and print a gesture crib sheet from www.goo.gl/KTaFXJ

Stats: 200g, 20 hours battery life, $249US

Alternatives: Build your own with BlueFly TTL or an Android tablet running XCSoar

Syride Nav

Just as you’re about to ring your old removals company, you get a sales call. “Here, you don’t need that big old lorry coming for your stuff – just use me and my minivan!” Say hello to the Syride Nav – a complete flight computer, but in miniature.

If you’re the sort of pilot who has a lightweight harness and replaces his shoelaces with microlines to save more weight, the Nav’s 83g will make it very tempting. It’s a great, unobtrusive instrument with four screens with up to six customisable data fields on each, with three buttons on the front.

Airspace maps and warnings, wind direction and speed and a G-force meter are all in the mix – and it’s chargable via USB, giving 20 hours’ life. Does nearly everything, but in mini! Syride also have an online route-maker, making task planning easy.

Marcus King has been using one for a while on his tandem, where one of the benefits is it can be attached to the risers with velcro loops, where the pilot can see it. “I’ve managed several flights without the need for recharging,” he says, “and never had issues with the battery of the GPS version.” Compared with previous versions improvements also now include a better safety leash that clips into one of your main karabiners.

It starts logging your flight automatically, as soon as you take off, we did think it would be nice to have a manual start for hike-and-fly adventures or if you want to use the logger for some other activity. But it’s a great choice for adventure pilots who need to save every gram but retain funtions, or anyone who simply wants to pack light.

Pros: Light and tiny fully functioning flight computer, good length of battery life

Cons: Small screen, not great for airspace

Tip: Don’t forget to add the navigation helper to the standard screens before trying to fly a task.

Stats: 83g, 20 hours battery life, €399

Alternatives: Ascent Vario or Skydrop (no airspace or task navigation)

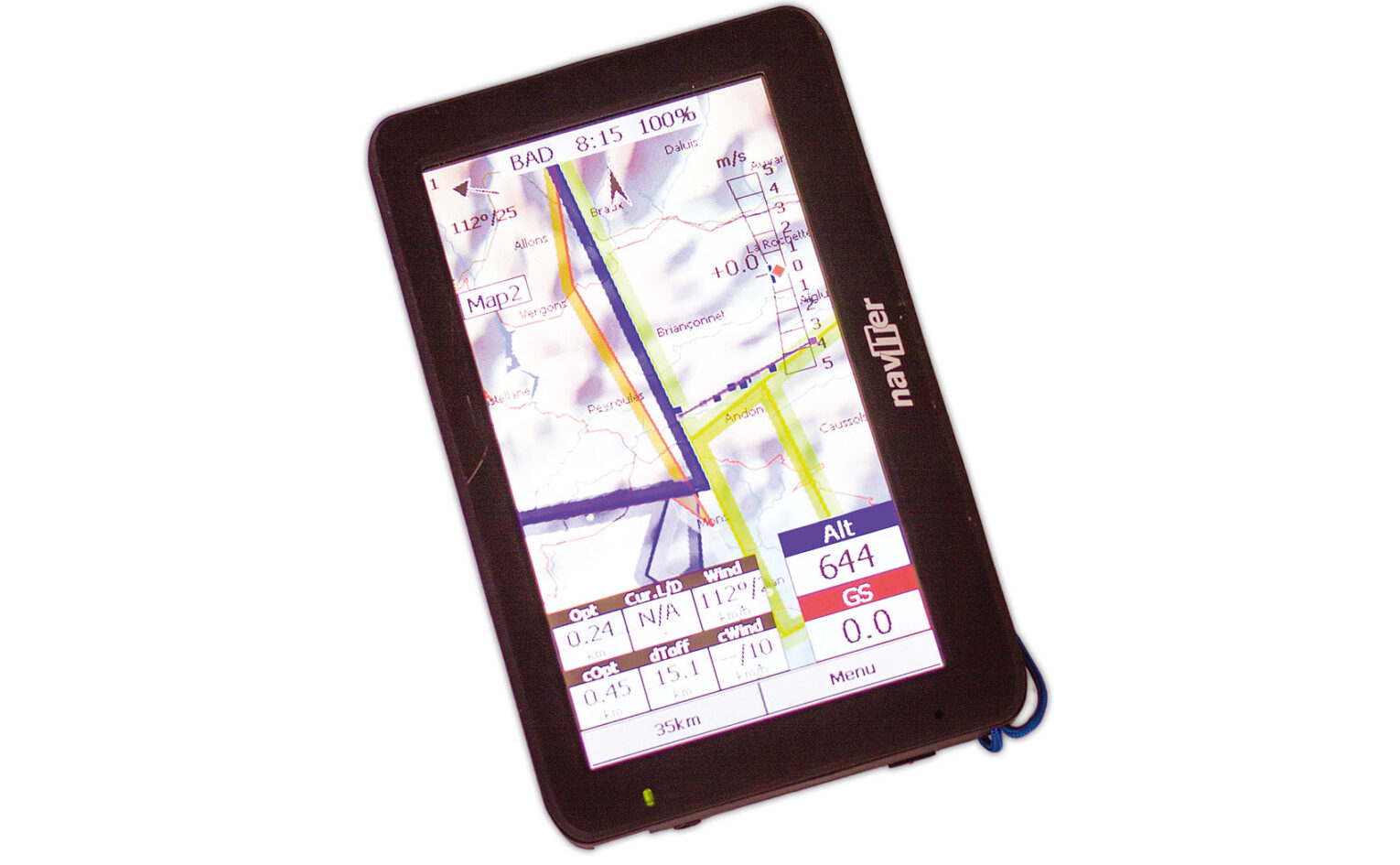

Naviter Oudie 3

If you were moving house and the removals company turned up, the Oudie 3 would be the huge bloke running up and down the stairs carrying three sofas and your dog all at once. Unfortunately sometimes a lamp might get knocked over or some wall plaster chipped, but the job would get done pretty much by one man alone.

The Oudie 3 is designed to do it all, with more features and functionality than any other instrument out there – and it does it pretty well. However, it was designed primarily for sailplane pilots (the handbook shows it sucker-mounted to a cockpit screen) and can be a bit fiddly for us cold-fingered, glove wearing, cloud surfing hooligans.

Much mocked by the self-build Kobo brigade for its cost, the Oudie 3 is slowly building a big fanbase of pilots who appreciate how quickly you can set and declare a new task on the hill right before taking off. It’s also supplied with SeeYou planning and analysis software, and connecting the unit to a computer means it acts like a mobile drive, allowing you to retrieve IGC files and save waypoints to it.

The Oudie’s battery life isn’t great – around 6-10 hours depending on the air temperature and audio volume – and I have sometimes found myself listening to the low battery warning on long cross-country flights, but Naviter now supply a power cable so you can hook it up to an external battery for extended life.

But with worldwide airspace, FAI triangle calculator and too much black art wizardry to fit in this article, many pilots are persuaded by one simple fact: why take two or three instruments to the hill when one will do?

Pros: Does-it-all including C records, triangle calculator, FLARM etc, colour screen, fully customisable data fields both on unit and on PC

Cons: Fiddly to zoom in and out, screen can get cluttered, heavy, short battery life

Tip: Turn vario sound off to dramatically increase battery life

Stats: 345g, 5-12 hours battery life, €798

Alternatives: Compass C-Pilot Pro Evo, Compass XC Pilot, VerticaSports V2

Flymaster Live SD

To continue the removals van analogy, the Live SD is the assured old hand who’s run the company for years. He’s stronger and wiser than he looks, and utterly dependable. He’s the one that will oversee the safe movement of that fine old armchair around that tight corner and down the corridor without so much as touching the paintwork.

The Live SD is utterly dependable, and its predecessors in the Flymaster family have an admiring following in the flying world. Featuring membrane-covered buttons

(yes, no touchscreen – how oldschool cool is that), the Live SD is really easy to operate, but following Charles Cazauz’s advice, you shouldn’t need to touch it while you’re gunning through the skies: all the information is right there.

A magnetic compass and an accelerometer have been added to the array of sensors, which give more accurate direction – useful if you find yourself sucked into cloud.

We have flown our review units a lot and confirm Flymaster’s claim of 30 hours battery life, even in cold conditions.

Live Tracking requires a dedicated SIM card – you might want to just use your phone for that, but if you’re travelling, a roaming SIM from OneSim is a great cheap solution.

Our previous gripe of not being able to send end-of-flight notifications has been fixed – with a dedicated menu allowing you to send a series of fixed messages, including being able to report condition levels during a task, one of the signs of Flymaster’s cooperation with the PWC.

Pros: Tough, conventional instrument, long battery life, can sync with airspeed probe C-records, triangle assistant and live tracking. clear screen, customisable at home on your PC

Cons: Expensive, but a really reliable main instrument

Tip: It’s got airspace maps, but consider getting a second instrument for dedicated navigation

Stats: 232g, 30 hours battery life, €689

Alternatives: Flytec Connect 1, Aircotec XC Trainer, Digifly AIR BT

The Future’s bright

So what’s the future of flight computers, with more apps becoming available running on tablets and phones?

Flymaster’s Nuno Gomes feels there will always be a market for specialist manufacturers. “Tablets and smartphones are not developed to be used as flight instruments, so they will always have a lot of disadvantages,” he told us. “For sure future instruments will be closer to tablets and phones, with colour displays and different interfaces, etc, but I think that there will always be some space for dedicated flight instruments. The great majority of instruments sold are the basic ones.”

What most of the manufacturers agree on is that dedicated instruments can offer good, solid ergonomics. Flytec’s Joerg Ewald agrees. “Often the vario with the most bells and whistles looks the most attractive,” he says. “Out on the hill, six weeks after your last flight, the vario that is operated most intuitively, and works the easiest, often turns out to be far better suited to help you enjoy a stress-free time in the air.”

Others say we will see a move from proprietary technology to standard platforms and from isolated devices to interconnected sensors and display units. That’s a view shared by Karl Rege, a professor at the Zurich University of Applied Sciences. Karl and a team of students have been working on a head-up-display making use of Google Glass to show vital flight data and warn pilots of hazards around them such as power lines. “Google Glass is the ideal display unit,” says Karl. “It is readable outdoors under direct sunlight conditions, and it’s safer to fly with than an instrument you have to keep glancing down at on your flight deck.”

He adds: “It does impair your field of vision a little but the fact that it is only one eye means you can fade it out. The programmability of Google Glass and the development tools are superior to others, and our software is now in the final testing stage.”

The USA’s Aero Glass are also working on head-up displays. Although the current system is aimed at general aviation the company said they have specialisation of the system for free flight on their to-do list with displays of airspace and task navigation as well as flight data being possible. Although they are supporting Google Glass, other devices such as those made by Epson and ODG have a much larger display. This allows the company to display augmented reality with 3D airspace for instance, overlaid on what you are seeing.

Is it coming soon? Aero Glass’s Jeffrey Johnson told us, “We are solving some key technical challenges and hope to have the product on the market in the second quarter of 2015”.

Karl Rege’s work

www.youtu.be/L6T7K69P4k8

www.glass.aero

C-Records

C-records store your declared task in an IGC file. Not all leagues support them and not all instruments support them. Here’s what the manufacturers say:

Flytec support C records in their instruments. Boss Joerg Ewald said: “Most pilots use this without even noticing; whenever you fly with an activated route the information is stored in the resulting IGC file. Waypoint definition through clicking on a map is a feature we have on our roadmap for future devices.”

Naviter support C records on their Oudie3 instrument. Waypoints can be created directly on the map display by clicking on the screen.

Aircotec do not currently support C records.

Digifly are “Evaluating whether to include it in the new firmware which we are currently working on, together with the airspace function.”

Flymaster told us: “The pilot simply defines a task (as is done for comps) prior to starting the flight. Once the flight starts, changing the task has no effect. A snapshot of the task is stored in the IGC at the start of the flight.”

ASI do not currently support C records, as there is no way of setting a task. They are looking at adding this in a future device.

Buying Secondhand

Flymaster B1-Nav: the classic 2 instrument that does (nearly) everything apart from C-records and airspace navigation. Good units sell for around €25-3.

Aircotec XC Trainer: one of the first competition GPS-varios. It might only have three buttons but has lots of functionality and they can even talk to each other like Furbies. Later models have USB for easy connection to a computer. Pick one up for €150.

Garmin 76S: ultra-reliable GPS. You’ll find one of these in the ‘man drawer’ of any longtime XC pilot along with some bluetack, an old Nokia phone, several paperclips and some keys to a bike-lock that’s been lost. Just steal it – they won’t even notice.

Flytec 6030: the weapon of choice for hang glider pilots due to its reliability, built in pitot airspeed indicator and total energy compensation. Rare as hens’ teeth!

If you enjoyed this sample article, perhaps you’d consider subscribing? A subscription is also a perfect gift for any pilot! Cross Country is a reader-supported international publication