What do we do, most of the time, while paragliding? We turn. So it is only fair to spend a bit of time pondering the implications of the most important turn of all: the one you do in thermals!

The standard way we measure this is the time it takes to do one full rotation, 360°, to fly a complete circle. It is sometimes possible to set this in your flight computer, to get your average climbing rate (the famous Vz). How interesting to see afterwards the thermal strength you got during your flight, or even to try and get the best average possible while airborne! One consideration leading to another, you always end up discussing the same question over and over again with your beer mates: should you turn tight or wide? Well, let’s try to give a definitive answer.

Bring in the data

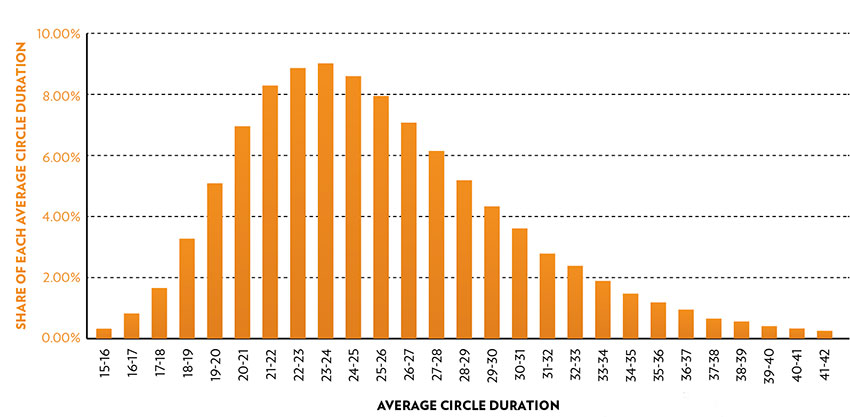

First, data is needed. A lot, actually! So let’s focus on the French Coupe Fédérale de Distance (the French Distance Cup – the national XC league), also known as CFD, to examine all the flights recorded, roughly 100,000. It is not very biased, as the terrain varies between flatlands, high hills (Vosges, Massif Central), and mountains (Pyrenees, Alps), and pilots fly all over the country. That is why to make sure the data was not skewed, we stuck to continental France. As you can see in Fig 1, this gives us the distribution of average circle duration in thermals for all the CFD flights.

This shows us that flights with the tightest turns in thermals take 15-16 seconds to complete the circle; while the largest average circles take 41-42 seconds to make. In other words, one pilot can do three circles while the other only one!

However, most of them are centred around 28 seconds, and a clever observer would have noticed that 50% of the flights have an average circle duration between 24 and 32 seconds. This is the landscape, now let’s have a closer look.

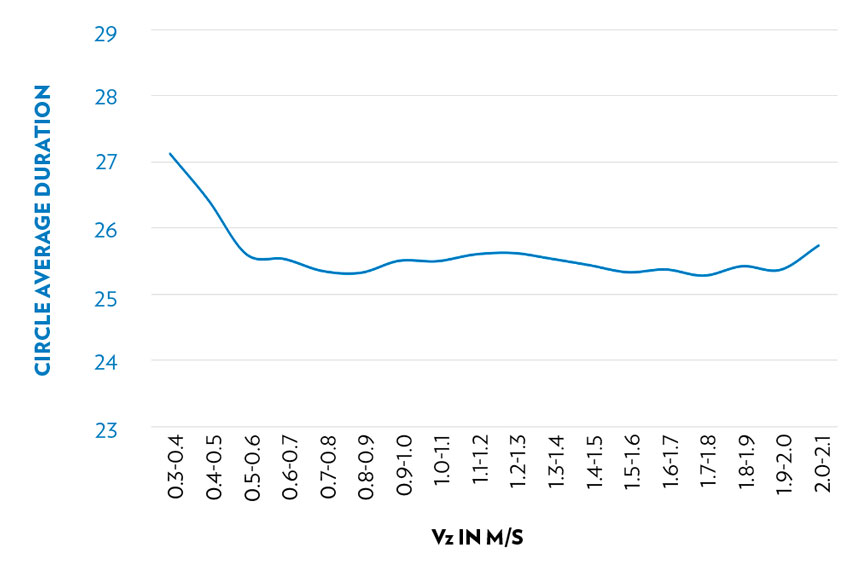

Vz is average climb rate. This shows that when the climb rate is weaker than 0.5m/s pilots fly slightly wider circles. When it starts to get stronger they plateau at 25-26 seconds

Flat or tight?

First thing you must have heard is that circle duration varies with the mean Vz (average climb rate) of thermals. Some think that when the lift is weak, you turn flat, so you make larger circles, and you tighten when it is strong; and others think the opposite. What does the data tell us?

Fig 2 shows us that pilots tend to slightly broaden their circles in weak conditions, only to reach a plateau between 25 and 26 seconds when the conditions deliver more than +0.5m/s on average. This dual situation says a lot about the importance of staying in the core, without degrading the sink rate too much when thermals are weak. It could also imply that thermals are indeed a bit spread out when they are frail. That’s also captivating, but I have not answered this question yet. Quite right!

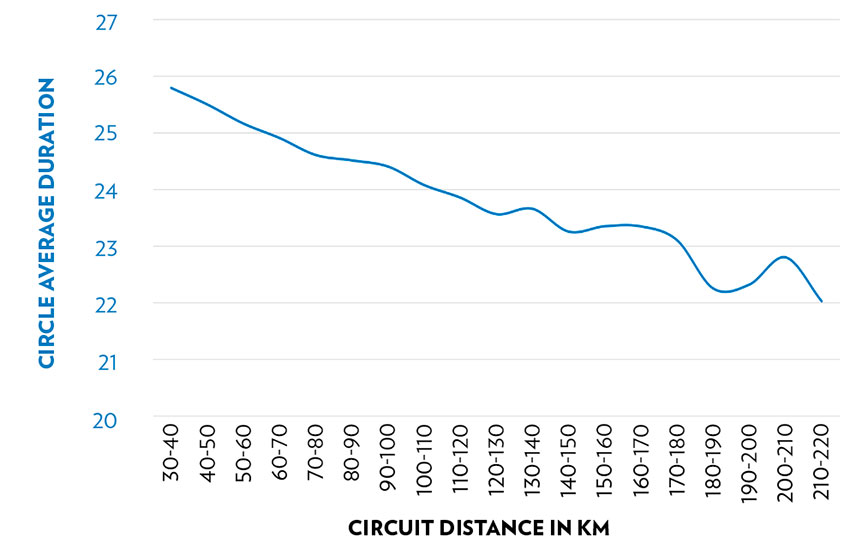

This shows that pilots who fly the furthest tend to have the tightest thermalling technique

How far?

Now that we have this first fact in mind, we can have a look at the distance, a good proxy for pilot level. Just a quick note before jumping in: the numbers or samples presented in those charts appear only when there are 100 flights or more to support their validity. That way, it is not really possible to be fooled by any secondary effect. That said, we can consider Fig 3.

It is clear that the further you go, the tighter you turn. Even if we imagine that conditions are stronger for the longest flights (higher Vz / average climb rate), we have seen that it has no significant impact on the circle duration. So, you might say that it could be related to the fact that the longest distances are usually flown with high-performance wings, which is true, and that those gliders flying faster than others have a shorter circle duration. Well, not really! Those gliders do fly faster, but not so much when flying circles when compared to other gliders: on average, 3km/h.

They also have a larger mean radius for the circle, which means it takes almost the same time to complete a 360° whatever the paraglider (for the curious readers, the standard deviation is roughly two seconds). There is indeed a linear relationship between the radius and the time to complete a full rotation. Now, you might begin to see where I am heading.

How tight is tight?

Ok, to recap, so far the data says that most pilots take about 27 seconds to complete a 360° in a thermal, and that this time does not really change on average once you have decent flying conditions. But one thing sticks out: the bigger the distance, the tighter the turns.

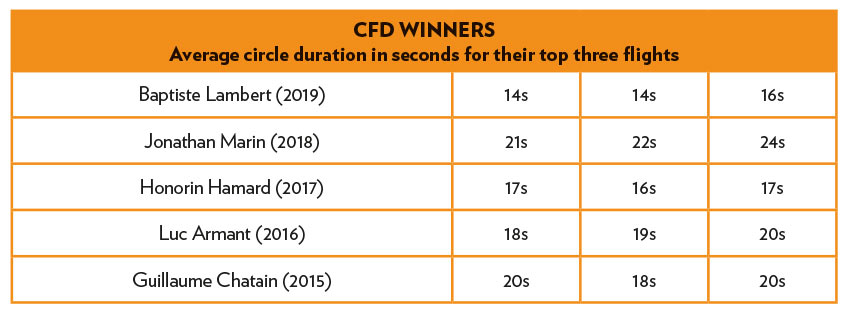

So, it is time to look at the best pilots and see what they really do. We can agree that the CFD winners will do the job, as they are also (mostly) top notch competitors. Here they are on the table (Fig 4) for the last five years, with the average circle duration for the top three flights that led them to win.

As you can see, they do turn tight, and especially Baptiste! In fact, when you examine the circle duration of top cross-country and competition pilots, that is really a trait they almost all have in common. Most of the time, they are close to 20 seconds or below.

So, what does it mean to turn tight? Well, from what we have observed, it is safe to say that it means completing a 360° in a thermal in 25 seconds or less. And to answer the question, yes, you should learn to turn tight.

But the “learn” is important, as it is part of the progression of becoming a better pilot. Honorin Hamard, for example, had a circle duration of 23 seconds on average in 2009, but sat at about 18 seconds in 2017. The more you progress, the more you are able to detect and centre precisely the core of the lift, and in doing so you narrow your turns to stay in it, and optimise your climb rate.

Performance marker

You can definitely say then that this number does, a few exceptions apart, reflect your level in paragliding. At XC Analytics, this is something we call a “performance marker”: a reliable indicator of the pilot’s skills, something that you should aim at as you progress in the discipline. It is opposite to what we call “style markers”, indicators that dependably describe the way you behave in the air mass, and that is specific to each pilot. But that is another story!

Martin Morlet was the first pilot to break 400km in France, and runs the website and app XC Analytics. He lives in Fontainebleau, near Paris