If the conditions are right cloud streets will form over flatlands. Just as in the mountains these are the days when the lucky pilot can really go far in a short time. Burkhard Martens explains more

The necessary conditions for cloud-street formation in flatlands are as follows:

- While the wind direction must remain pretty constant at all levels, wind speed should increase with altitude

- Wind strength should be highest in the upper one-third of the space between the ground and the top of the cloud

- There should be an inversion present at an altitude corresponding to the cloudbase; the clouds must have vertical room for a healthy development but they cannot be allowed to grow too big. An inversion around 1,000m above the condensation level is probably around right.

When all these conditions are met we can expect the distance between the cloud streets to be 2.5 to 3 times the distance ground-to-cloud top. If the clouds grow to 3,000m above ground the next cloud street will probably be approximately 7-9km away, and the cloud streets will be aligned with the wind.

Here’s a tip

Here are two things to consider when using cloud streets to fly in flatlands:

- If the gap between two clouds in a street is greater than the distance to the next parallel street it is probably wiser to change streets.

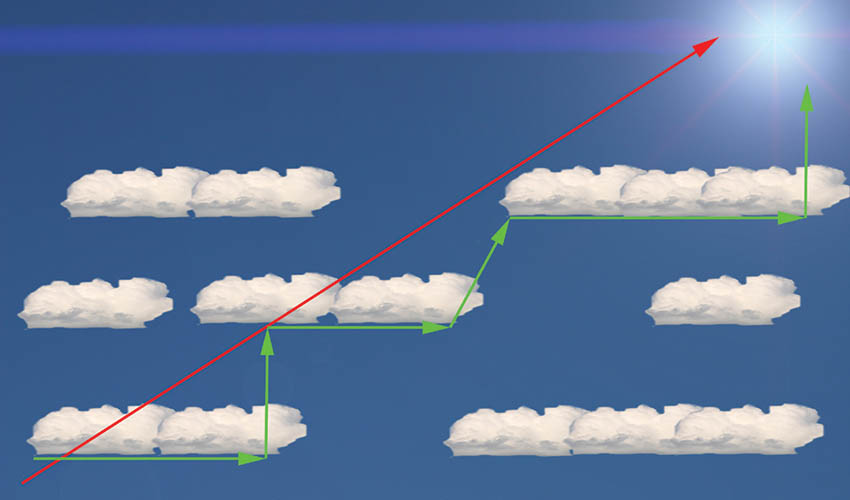

- If your bearing is at an angle to the cloud streets it pays to go as far as possible along the streets and change street when a gap in your current street appears.

In the illustration above the planned direction is in red and the most efficient line is in green. The gaps in the cloud streets are used to change streets and move in the desired direction. Big gaps in cloud streets are also better negotiated by changing street than by attempting to cross large blue holes.

Dolphin flying

Dolphin flying, or dolphining, is the fastest and most efficient way to put some kilometres behind us when flying XC.

When dolphining the pilot simply flies straight, braking in lift and accelerating in sink. The trick is to adjust the speed exactly so that the net altitude remains the same over time, and this is something that takes a lot of practice.

Near cloudbase we speed up and increase our sink rate so that we avoid getting sucked in. Lower down we may choose to fly closer to min. sink in order to get the most out of the lift at hand.

By constantly changing our speed we attempt to remain roughly within the area of the best climbing, normally quite close to the cloudbase. Once we have this dialled in we can experience some very satisfying flying.

This is an extract Burkhard Martens’ classic book Thermal Flying