A pilot has shared their terrifying story of being swept to more than 7,000m in a storm cloud while paragliding in Bir, in the Indian Himalaya.

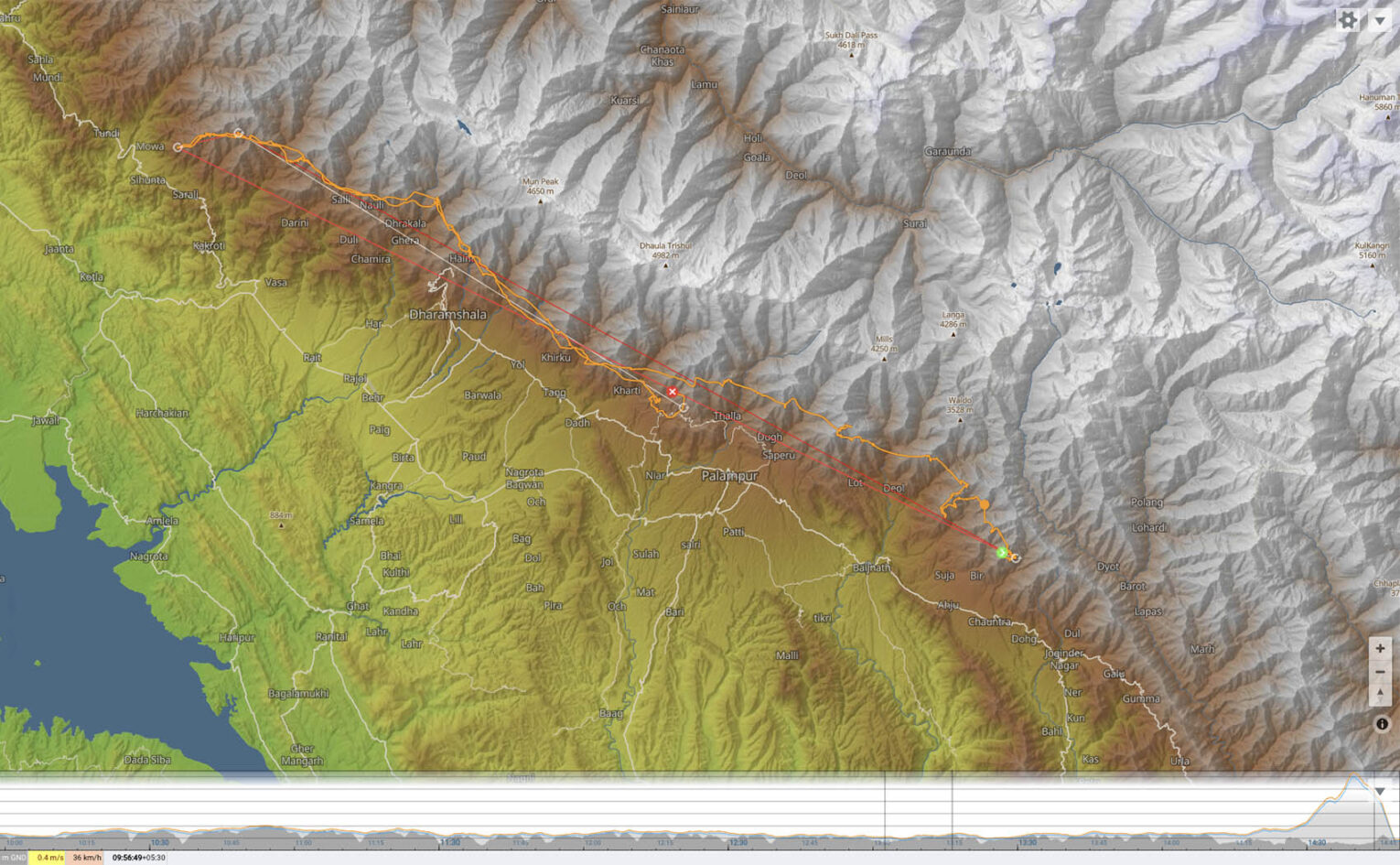

Ben Lewis, a Canadian pilot on a flying trip to Bir, also known as Billing, in the Indian State of Himachal Pradesh, was sucked to 7,374m at the end of a 100km long cross-country flight on Thursday, 17 October.

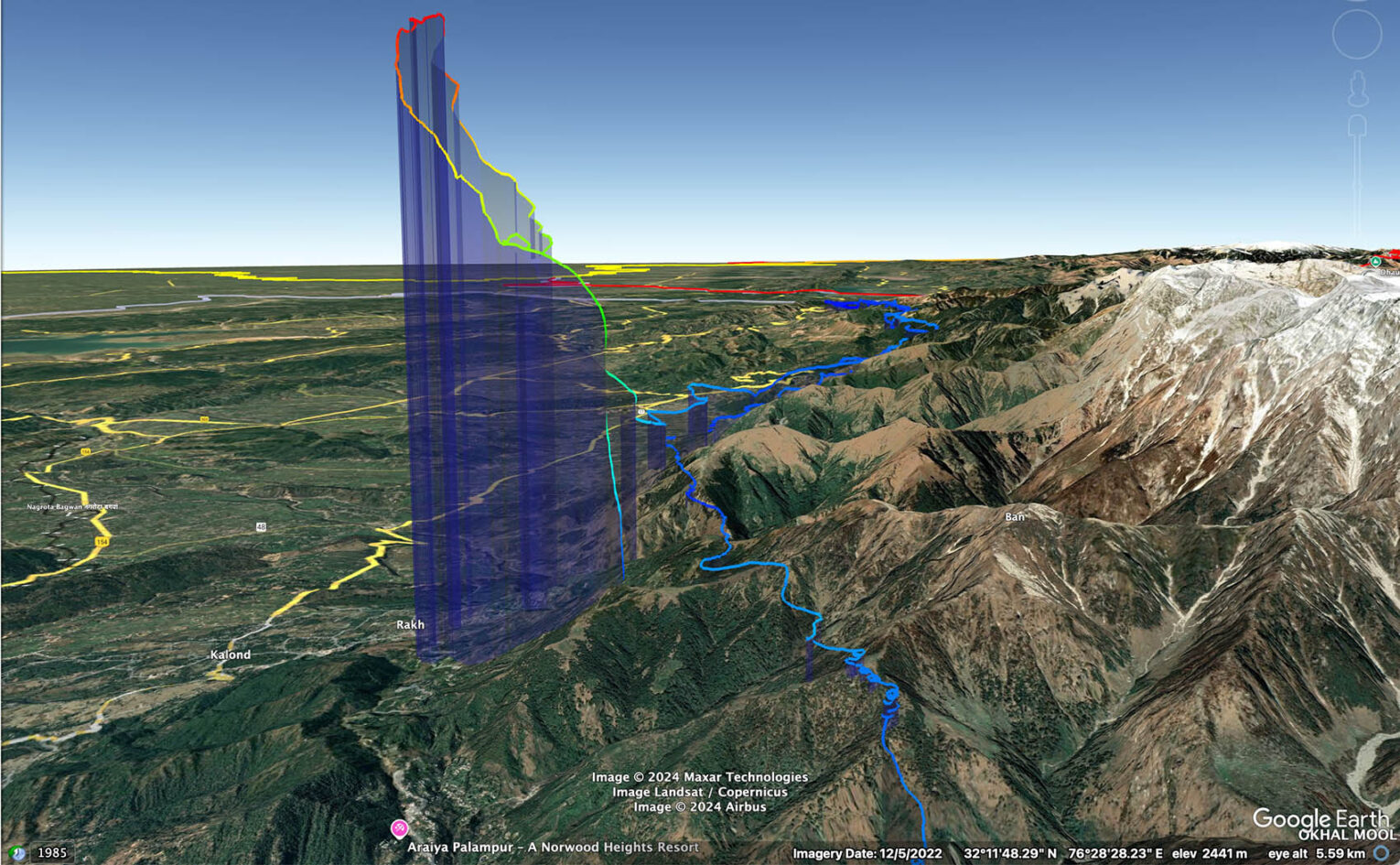

According to his tracklog Ben had been flying cross country for just under five hours when weather conditions overdeveloped and he was hoovered up by a large cumulonimbus, or storm cloud.

In just 10 minutes he was swept up from 3,000m AMSL to above 7,000m – reaching a maximum climb rate under his paraglider of 16.3m/s, or nearly 60km/h.

After fighting and failing to regain control of his glider and his horrifying ascent rate he resigned himself to his death and blacked out at around 7,000m AMSL.

However, he did not die but woke “surprised” to find himself back on the ground, hanging in a tree and still attached to his paraglider, an Ozone Alpina 4 (EN C). His tracklog shows he almost plummeted to earth in the strong downdraughts associated with the storm, with a maximum sink rate of 19m/s or 68km/h. The ordeal in flight lasted 20 minutes.

Suffering from injuries which included frost-bitten hands, retinal bleeding, a frozen cornea, ruptured eardrum, a badly bitten tongue and rib fractures he then endured a long self-rescue before being found by a local mountain family who took him into their home. He was later retrieved by his flying friends who then hiked out with him to the nearest road where they had a hired taxi waiting to take him to hospital.

Posting on XContest, an online XC contest for paraglider pilots, Ben wrote:

“I’m uploading this in the hopes that it can be a cautionary tale for others not to make the same mistakes.

“I think the previous couple weeks of flying around Bir with large threatening clouds actually being fairly benign lulled me into a state of overconfidence. I ignored multiple clear warning signs.

“By the time I reacted, it was too late to effectively change my heading or control my altitude. The storm was incredibly violent and I had no control. I blacked out somewhere near the top of my climb, I think more from G-forces in the spiral climb than hypoxia.

“The forces were so great I wasn’t able to sit forward in my harness and ultimately just hung there arched and resigned. I thought about trying to cut my lines with my hook knife but my hands were too cold. I was sure I was going to die.

“My last thoughts were of my family and I was profoundly sad and remorseful about leaving them like this.

“I was surprised to wake up hanging in the trees about a metre off the ground. It was hailing and my hands were frozen. My vision was very poor (I had frozen my left cornea so my left eye was essentially blind and on the right side, I had retinal bleeding obscuring most of my central vision).

“My left eardrum had ruptured. I had bitten deep into my tongue. I had posterior rib fracture(s) on the right and a left shoulder separation (A/C joint) and just lots of muscular neck and back pain. Luckily though I had no spine or limb fractures.

“I sat under my quick-pack tarp, breathing on my hands for maybe 30 minutes. The hail turned to rain and then stopped. I had no reception but I did know my location.

“Getting out of my harness and then clawing my way down the jungle river valley and finally scaling the ravine wall to reach cell reception before nightfall was the most agonizing two hours of my life. I was able to contact my friends who then helped organize a rescue.

“A local family came and found me on the hillside in the dark and guided me to their house (literally holding my hand as I was essentially blind in the darkness) where they warmed up my hands and feet by rubbing hot water and oil on them, caringly plucked out all the plant spines, and gave me warm fluids.

“I was overwhelmed by their generosity and they refused any offers of payment. My awesome friends showed up to the house a while later with dry clothes and we hiked down to the waiting taxi after a tearful farewell with the family.

“I feel just so incredibly lucky to be alive and thankful for everyone involved with rescuing me. Three days later, I’m still in a world of pain but things are improving, I can mostly use my fingers again and even my vision is slowly improving.

“All I can hope for is that other pilots reading this learn from my mistakes and give clouds/storms the proper respect they deserve. Safe flying everyone.”

Several other pilots were affected by the storm, with nine incidents reported, including three reserve deployments in the vicinity on the day.

Flying near storms

Ben is not the first paraglider, hang glider or balloon pilot to have been sucked into a storm cloud. He is, however, one of the few to have survived such a close call with the experience.

Most famously, German paraglider pilot Ewa Wisnierska, then 35, survived when she was carried “higher than Everest” to 9,144m while flying in Manilla, Australia in August 2007. China’s He Zhongpin, 42, died after being struck by lightning in the same storm.

In Bir, Russian pilot Alexey Ashurov went missing while paragliding in 2009. His body was found nine months later.

And in 2002 British pilot Joel Kitchen vanished without trace while flying in the mountains around Bir. A backpacker who had learned to fly while in India he was last seen at 3,350m before he “vanished in a cloud”. His body was never found.

Bir/Billing is a popular adventure paragliding destination for paraglider pilots from around the world who flock there in the main flying season of October to November.

Cumulonimbus clouds are large storm clouds that can reach heights of 12,000m or 39,000ft – about the cruising height of an airliner. Pilots of all aircraft avoid them if they can.

Podcast: Listen to Ben Lewis talking with Cloudbase Mayhem podcast host Gavin McClurg