There’s simply nothing worse than a stable day with weak thermals and lots of turbulence. They are generally lots of stress for little reward, but if you want to be a good all round pilot you have to learn to fly in all conditions. Bob Drury explains what to do.

First, understand why it’s rough on stable days. Stable days are caused by high pressure systems, where the air particles are generally sinking earthwards. That alone makes a thermal’s ascent more difficult, but in mountains you generally need to be in a high pressure to get good flying conditions; low pressure produces too much instability and it storms. Worse still, sinking air particles cause adiabatic compression which creates heat. This forms bands of warmer air which we call inversions. Inversions trap air beneath them, and this lower air then warms up more than on unstable days where the upper and lower air gets mixed more by thermals.

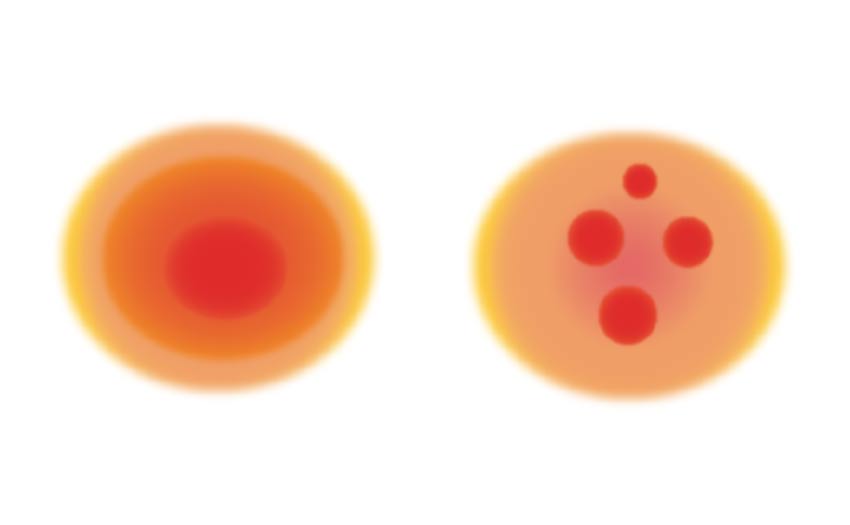

The net result is that it is harder for thermals to form and harder still for them to rise once they have enough buoyancy to actually break free of the ground. As the air is warm and stable there is a low temperature difference between the thermal and the air it’s travelling through, so the climb rates are weak. As the air surrounding the thermal is almost the same temperature as the air inside the thermal it doesn’t take long until all the weak lift dissolves into the surrounding air. All that is left are tiny hotspots or micro cores. Sharp edged and rocket-like in comparison to the soupy air you’re flying in, they hit you like missiles out of the blue and you’re through them and out the other side before you’ve had time to think, “What the hell was that?” There’s the roughness on an otherwise weak day.

Success on these days requires a combination of two separate tactics.

Search mode: Wide and slow. Covering as much ground as possible with the best sink rate. The chances are you’ll encounter wide areas of weak lift in the general stable ambiance.

Climb mode: Tight and fast. When you hit the micro cores crank as hard and tight as you dare and hang on for your life. You might only get half a turn in lift, but crank it round the whole 360 and see if you hit it again. Often you can climb like this in little surges with only half your circle in lift. Watch your averager to see if it’s working.

Need to Know

This is an extract from Fifty Ways to Fly Better by Bruce Goldsmith and friends.