By John Dunham

In the early 1970s, free flying at its very rawest: exhilarating, dangerous, and with everything yet to be discovered. This is the story of one of the very first ever cross-country flights – if not the first ever. “There’s something about being in the air more than a mile up and not worrying where or even when to land, writes John. “If only there had been other clouds like this one downwind, I could have gone until sunset.” It’s the perfect story to end this series on. We hope you’ve enjoyed it!

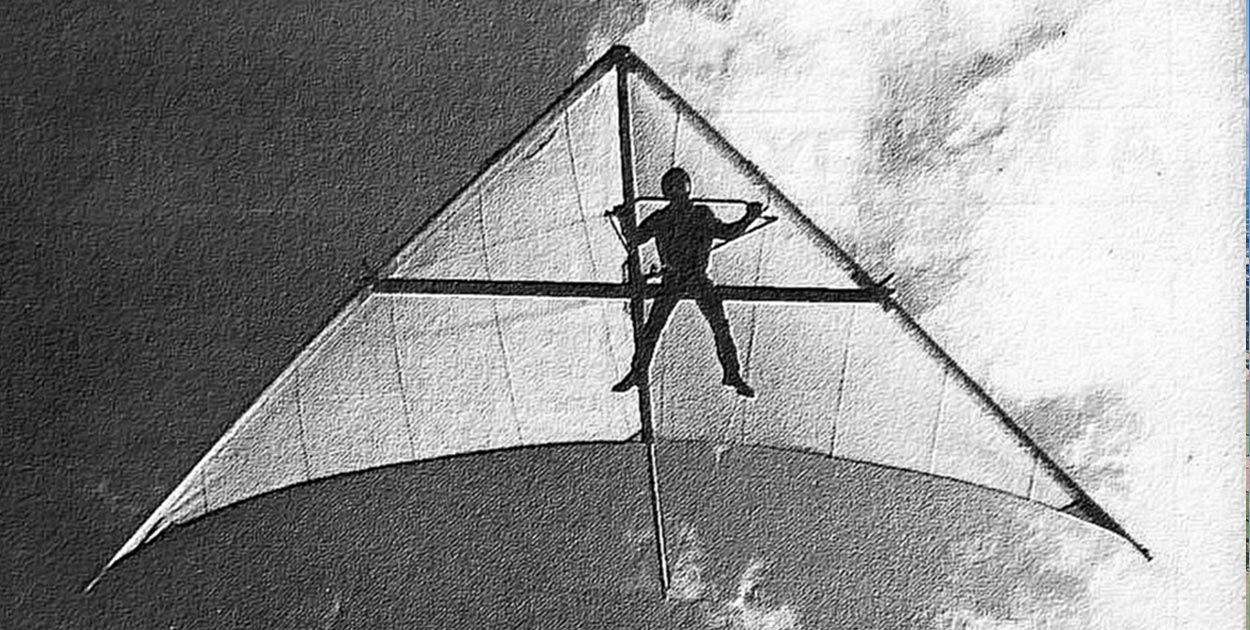

A cross-country flight in July 1974 was as yet a dream for most pilots. I believe that this story was the first such to be published and that my flight was the longest in the world at that time. The flight was done on a home-built ‘Windlord’ standard wing, with an Albatross sail. It might not seem such a great accomplishment today, but consider this: I was flying a 5:1 glide ratio wing that weighed only 38 pounds. I had no variometer. I had no parachute. There were no other cross-country pilots to learn from and the most important thing… I was too young and too dumb to be afraid!

Teluride, Colorado, site of the Rocky Mountains Hang Gliding Championships, July 1974. It’s one of those places you hate to leave because you’re firmly convinced that this must be paradise. After the most enjoyable, relaxing nine days of flying I’d ever experienced, it was time to say goodbye and head for parts unknown. There I was in my hammock slung between two Aspen trees, catching some sleep before our last morning in the Rockies. Reggie Jones and I were tentatively planning to leave the next day to scope out some new flying spots in Arizona’s White Mountains before heading home to San Diego.

2:30 am: I slowly awoke from my dreams to find myself deeply involved in a conversation with Bob Dart and Lloyd Short, winner of that day’s contest.

“Come with us to the Butte, John. It’s paradise! The most outrageous place you will ever fly! It will be a great place to take your Windlord for some cross-country flying! The only direction the air goes out there is up! Everywhere you fly there’s lift. Thermals! Ridge lift! Soaring! It’s unreal! There is so much lift you could drive to the base of the mountain and fly up! Without your kite!”

“Sure, Bob,” said I, “What was it you and the gang were doing at the tavern tonight?”

Well, half asleep or not, I wasn’t going to let all this exciting talk keep me from making a rational decision. So, finally I gave Bob and Lloyd a definite answer: “I’ll think about it”. And I promptly fell back to sleep, wondering where in hell the ‘Butte’ was.

By the time I fully realised what I was doing, we were in Salt Lake City headed for Idaho Falls in Lloyd’s truck – with Mike Mitchell, Curt Stahl and friends tagging along behind chanting, “goin’ to da Butte” in four-part harmony.

Arriving in Idaho Falls on Wednesday we met with the local crazy kite flyers from “Soaring Sports” and spent the night in town as their guests. It seems they were planning a get-together at the “Butte” that weekend and were happy to share their secret mountain with us. Bright and early Thursday afternoon, we had a barrage of kite flyers “headin’ to da Butte” through fifty miles of flat desolate desert.

The first time I saw that mountain I was truly amazed. Picture a flat desert as far as you can see, with nothing but sagebrush and dark lava beds spotted here and there generating heat into the sky. On an average afternoon you can see dust devils as large as white tornadoes being sucked up seemingly into fluffy white marshmallow clouds lined up in streets as far as the eye can see. Out of this ocean of nothingness jolt three volcano-like mountains spread out fifteen miles across the desert. The largest and farthest west of these hills, better known as ‘Big Southern Butte’, juts up 2,500 feet from base to top and has a passable dirt road which will take you in any direction. A southwest wind prevails here this time of year (July) which is perfect for a take-off at the 1,900 feet level that’s as easy and clean as you could hope for. For almost a mile you have a smooth, soarable face on the mountain dropping off into a desert which looks like an ocean from the top. Your landing area is anywhere – no obstructions, fences, power-lines, trees, nothing.

Our first flight Thursday wasn’t much. It was not quite soarable, and there was no thermal activity to speak of. But after an incredibly smooth sunset flight off the north slope, we were ready to stick around another couple of days.

“You should have been here last week!” said one of the local flyers.

Where have I heard that before…

That night we camped at ‘Frenchman’s cabin’ in the landing area four miles from the usual flying spot on the mountain. There’s an old airstrip with a windsock next to the cabin. It couldn’t have been more perfectly situated. Nobody minds people camping there as long as they leave things as clean or cleaner than they find them.

Friday was marked by three decent flights and a rolled-over kite truck. Apart from the setback of having to spend the afternoon and half the next day pulling Lloyd’s truck out of the gully that it ended upside down in, everyone was having a good time, and Lloyd’s truck was still running like new – minus a front windshield. Still, nothing spectacular had happened in the air.

Saturday: Feeling burnt out and ready to call it quits after two mediocre flights, we were sitting at the cabin contemplating our travels when all of a sudden small white fluffy thermal clouds began to billow out everywhere we could see. Also, the wind seemed to be picking up in a decent direction. Rushing up the mountain in Lloyd’s truck at sixty mph with no front windshield was an exciting experience. What was even more exciting was to see the wind blowing up the face in a perfect direction at 20 mph – more or less.

Throwing our kites together, we were ready to go… but who’s first? After having been wind dummy the last two days, I proceeded to the end of the line and watched the circus start. Keith Nichols of San Diego decided to be the dummy in his Seagull. Two light steps and he was off. Keith looked tense as if he was expecting to get thrown around, but we were all surprised. It looked like a smooth day at Torrey Pines (Southern California) with five times the lift. Keith went up and out for a quarter mile before turning and was still going up. Mike and Curt, then me and then Bob. It was now 5:30 pm and there was plenty of time before sunset, which was not until about 9:00 at that time of year, so we had lots of daylight to play around in.

Here we all were, driving around in the sky above the ‘Butte’ having a grand ol’ time in air smooth as silk. Not having paid any attention to my altimeter earlier, I was surprised to realise that Mike and I were now about 1,000 feet above take-off even though we were way out in front of everyone else soaring the ridge below us. Mike was doing his fancy 360s in front of me as I sat hovering and conserving my energy. After about fifteen minutes of soaring, Mike and I had 1,200 feet over the take-off.

It now seemed as if we had worked ourselves into the horizontal flow of air and were having problems penetrating away from the ridge. No problem. Almost as if someone blew a horn, everyone started crabbing out away from the mountain to the north and headed for our landing area four miles away. Leaving the mountain, my altimeter now read 3,200 feet above the desert floor. Everyone else headed for the cabin, more or less in a straight line, playing around for a long time until they landed on the airstrip. Meanwhile, with my eye on a sunny patch of ground and a developing cumulus, I headed downwind of everyone else and was surprised to see the needle of my altimeter creep up to 3,500 feet as I headed out over the flat desert.

There I was, 3,500 feet up and wondering where to go next. There was no need for a variometer because the lift seemed to be everywhere. After flying around sort of pointlessly, I turned around and headed back to the landing area and found the headwinds too strong to penetrate. Then and there I made up my mind not to fight it. Turning downwind, I headed for the cumulus cloud which was looking darker and larger all the time.

For as far as I could see there was nothing but desert spotted here and there with Atomic Energy Commission installations and a few dirt access roads. Ten miles to the north of the Butte, the main highway cut through the desert. I figured my best bet would be to head for the highway and follow it downwind, but for now, I wanted to play around with that cloud. Making a few long passes underneath it, I was surprised to see the needle of my vario climbing at a very fast rate, and getting faster all the time. Nearing the base of the cloud, I was beginning to worry.

The wind was getting interesting, to say the least. At one moment it would feel like there was a strong headwind – then cross, tail and every which direction. There was nothing violent as far as turbulence goes. At my highest point my meter read 5,500 feet over the desert floor. At that time I was looking at the base of the cloud perhaps 500 feet above me and getting heavy rain in my face. Due to the fact that I had no shirt on and that I was getting sucked up at a faster and faster rate, I pointed my ‘point-nose parachute’ for clear sky. Breaking out from under the cloud, my sail inverted violently and I was thrown around a bit, but things smoothed out quickly. There was a surprising temperature change now and the warm air felt good for a while.

Seeing that my altitude was dropping at a sickening rate, and because the cloud was now between me and the highway to the north, I decided to go for another swim. Wham! Through the turbulence, back under the cloud; it was elevator time again. Getting cold and wet didn’t seem to matter anymore. You never saw a happier, more free-spirited pilot than I was under that cloud. There’s something about being in the air more than a mile up and not worrying where or even when to land. If only there had been other clouds like this one downwind, I could have gone until sunset. With confidence in my machine and in my ability to cope with the situation at hand, the shackles were off. I was defying gravity. So it seemed for a while. This had to be the most refreshing, exhilarating experience I had ever encountered in my life.

After regaining my altitude of 5,500 feet I decided to fly out of the cloud, setting up max glide to the main highway. I almost turned around to head back to the cloud to play some more, but flying prone for almost an hour sometimes puts a strain on one’s body, and it was time to go for distance.

After a five-mile final glide I crossed Highway 26, turned upwind and settled down gently next to the camper of an older couple who were headed west on their summer vacation. With a grin from ear to ear, I walked up to their camper and said, “Hi!”

When they asked where I had come from, I pointed and said, “see that mountain way over there?”

“Yeah”.

“Well, I took off from the other side of it, flew up to that cloud, and finally ended up here!”

The couple looked at each other and broke out laughing. They asked if I needed any help.

“No thanks,” I replied. “My friends should be along any time to pick me up. Thanks anyway!”

After they drove away, I sat down and looked at the cloud I had just passed up and the mountain from which I had come. Ten minutes after I sat down, the cloud picked up its skirts and threw 30mph winds and the heaviest rain squall I’d ever seen at me. With a thunderous voice, it seemed to say, “Take that!” and headed slowly off to parts unknown. There I was sitting on the ground wishing I was going with it.

As it turned out, I had gained approximately 3,600 feet and travelled 11 miles downwind of the mountain. One of these days, hopefully next summer, I will encounter similar conditions. I hope I’m a little more prepared than I was last July. It is my dream to become as knowledgeable as the birds we’re trying to imitate in this sport, and to be free to go where they go. I feel like a guest in their ocean of air, and I’ll jump at any opportunity to learn firsthand what comes to them naturally. My thanks go out to the late Lloyd Short and my good friend Bob Dart for initiating this experience in the ultimate.

I would welcome contact from others who were flying cross-country at that time. It would be fun to put together a chronology of these ‘firsts’ in our sport. I believe Chris Price, then of Wills Wing, soon after flew 21 miles in Lakeview, Oregon. The rest is history!