Xavier Murillo took 12 years to track down and interview the ‘true father of paragliding’, David Barish. His interview, published in Cross Country magazine in 2001, shed new light on the history behind the invention of the sport of paragliding…

February 1988, Annemasse, France

Whilst researching my book “La folle Histoire du Parapente”, I met a parachutist from Annemasse: André Bohn, one of the three pioneers of paragliding in France. On Sunday 27 June 1978, André had launched from Mieussy and glided all the way down to the football pitch in the valley 1,000 m below. When I asked how he came upon he idea of foot-launching a ram-air parachute, André told me that he had seen it described in the “Parachute Manual”, a technical magazine by Dan Poynter written for professional parachutists.

This was a revelation to me, as it was now obvious that contrary to popular belief, paragliding wasn’t invented in Mieussy, France

even though it was there that the concept flourished through the passion and dedication of pioneers like Jean-Claude Bétemps, Gérard Bosson and the “Choucas” club of Mieussy.

January 1992, Melbourne, Australia

After a competition in Victoria, I paid a visit to the meet director who ran a small parachute factory in Melbourne. I discovered his complete year-on-year collection of the Parachute Manual, and I leafed through them, hungry for more information. The 1972 edition carried a description of “slope soaring”, described as a method of testing parachutes after a repair.

In the courtyard of the factory, I laid the book on the ground and photographed the pages. It served as proof that foot-launching had started as early as 1970! The black and white photographs show an astonishingly shaped wing. This was David Barish’s Sailwing machine, but I would only learn this fact eight years later. I would long regret my blatant lack of curiosity as to who the pilot was. Like me, no-one would push the investigation further.

January 1998, Musée de l’Air et de l’Espace, France

Rummaging around in the museum library, I found another book by Dan Poynter, titled “Hang Gliding” and dating back to 1973. What a find! More than two pages are dedicated to “paragliding”, which is described as being very similar to hang gliding. They are illustrated with the same photos as were used in the “Parachute Manual”. And here, the inventor of paragliding had a name – David Barish – and was described in the captions as being the promoter of the activity, having made several flights in the ski resorts of the USA.

I announced my discovery in the April 1998 issue of Parapente magazine in a story titled “Paragliding was born in the USA.” But the editor refused to publish my poor photo – the glider was too ugly! Fellow journalist Jean-Paul Budillon picked up on my lead and sniffed out the contact details of Dan Poynter and David Barish. I bought a plane ticket to New York.

3 June 2000, Manhattan, USA

51st Street, New York. 12th floor. A smiling gentleman opens the front door of his apartment to greet me. “Xavier?”, he enquires, stretching out his hand in welcome. It is the culmination of 12 years of searching for the legitimate father of paragliding. And over the next three days David Barish tells me the story of his life and his many inventions, amongst which is the paraglider.

In the spare room, where I am staying, David shows me the sewing machine he used to stitch his first designs, now stowed away under the bed. And sat on the shelf lies the wooden propeller, of the first paramotor!

David Barish started his flying career at the age of 18. In 1939 the US government was suffering a shortage of pilots, and was offering a free training programme to new recruits. ‘I was soon a co-pilot for TWA, flying transatlantic routes,’ he recalls. ‘My brother, who was three years older than me, was a bomber pilot flying the B17 flying Fortress, and was killed in the Normandy landings in 1944.

‘I joined the US Airforce soon after, and trained as a fighter pilot on the Mustang. But luckily, the day I graduated was the day Japan surrendered. The war was over.’

David then gained a place at the prestigious Cal Tech university, where he obtained a Masters degree in theoretical aerodynamics. He put it to good use by working for the Air Force’s Research and Development division at Dayton.

In 1953 he left the armed forces, but remained a consultant for the Air Force and NASA. In 1955 he designed the Vortex Ring, a revolutionary parachute consisting of four flexible wings rotating on an axis, producing the same effect as the blades of a helicopter.

With a better sink rate, a reduced opening shock, half the weight and no oscillation, the Vortex Ring was dubbed ‘the perfect parachute.’ Another advantage is that on landing, the Vortex Ring immediately folds itself up, even in a strong wind, which avoids it being dragged along the ground- quite an advantage for paraglider pilots! It was produced by Pioneer, the world’s leading manufacturer, and is still used today by the American army.

In the early 60s the space race was on, and huge amounts of money were thrown into development. It was this that triggered the invention of paragliders. In 1964 David Barish applied himself to the design of a parachute for bringing space capsules back to Earth.

To avoid manufacturing parachutes with spans of over 30 metres for carrying capsules weighing 5 tonnes, he made models of different sizes. He tested them behind his car, or by hand in a steady wind at Staten Island ferry.

The first Sailwing was single surfaced, rectangular shaped and made up of three lobes. The front of each panel was turned under and stitched to the undersurface along the seams joining the panels. This formed a double surface of over 30 cm. when inflated, it rigidified the leading edge.

David Barish comments: ‘NASA wouldn’t buy a double surface chute. But they also wanted a better glide. That’s why, in 1966, we progressed to the version with five lobes.

‘Then, the double surface part was extended to one third of the chord. It was Domina Jalbert who invented the entirely double surface parachute.

‘What else about the design? Well, I thought the enormous stabilisers were necessary. And spinnaker cloth was an obvious choice – if you want a wing, you need the lowest possible porosity.

‘I determined the length of the lines came from the experience of kite-flyers who already knew all there was to know on this subject.’

The first flight, in the company of his son and friend Jacques Istel, took place in September 1965 at Bel Air in the Cats Hills. This is a ski resort two hours from New York and not far from Woodstock (where Hendrix had not yet played Purple Haze and Little Wing!).

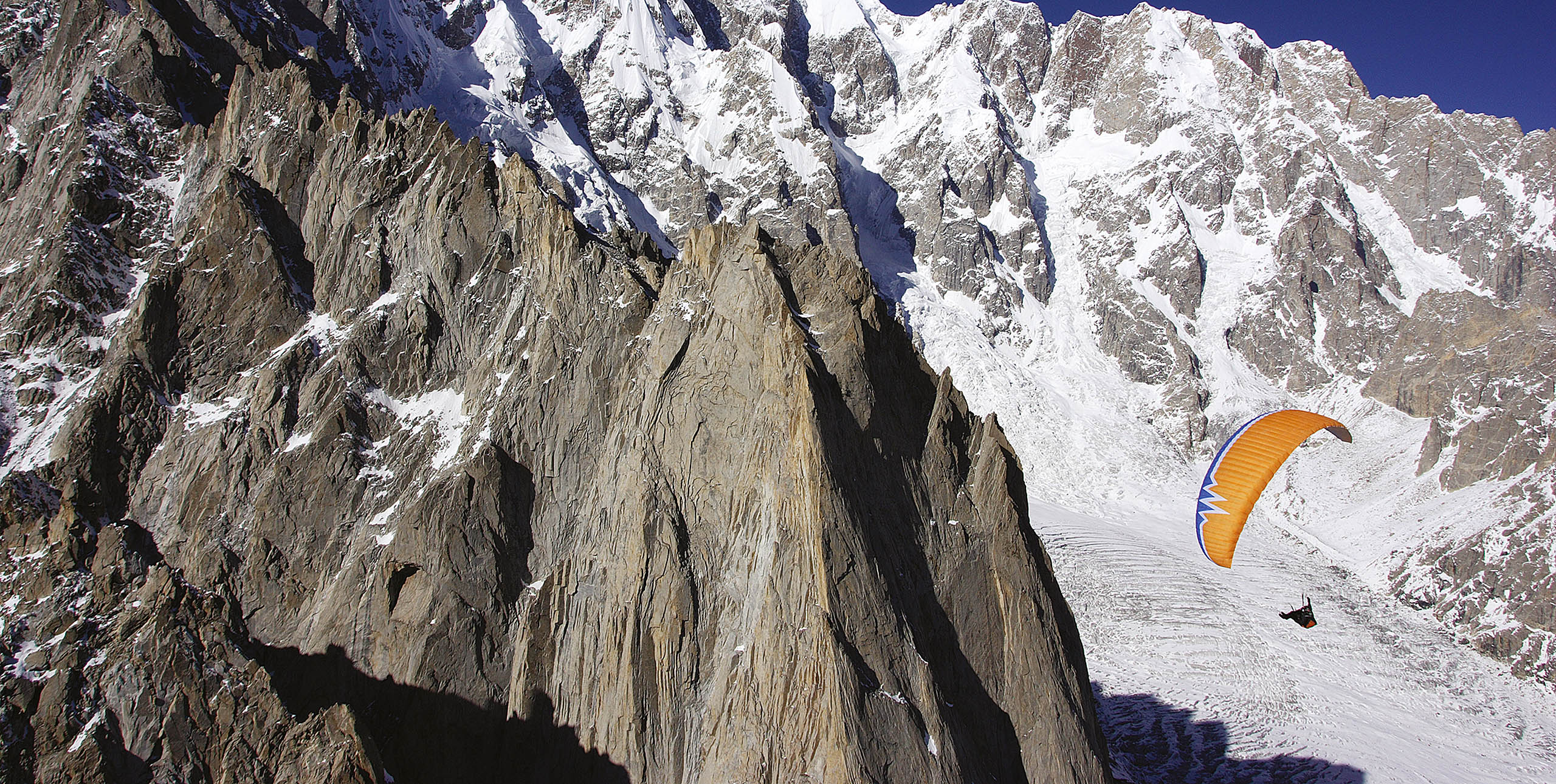

David often flew the slopes of Mount Hunter, in the same area. A keen skier, David Barish had a crazy idea: a new summer sport which would consist of skimming down the grassy slopes of the ski pistes. The new sport was christened “slope soaring”.

At the suggestion of a friend who was a journalist on “Ski Magazine’, he and his son did a tour of American ski resorts from Vermont to California in the summer of 1966. The aim was to demonstrate that “slope soaring” could be a viable summer activity in ski resorts

Of these barnstorming days, David remarked: ‘It was probably too soon! At that time slope soaring was just for fun.

‘We didn’t know that it might be possible to soar in thermals or dynamic wind. We just pushed the sport as being a fun way to race downhill.

‘We raced down the ski slopes, skimming the ground, rarely more than thirty metres up. I still managed to end up in the trees several times!’

In 1966, NASA was trying to finalise its choice for recovering the capsule of the Apollo space shuttle. For the next two years David worked hard on his project, trying to convince NASA of its benefits over the Rogallo design.

‘Francis Rogallo came to the wind tunnel one day during my tests’, said David. ‘He didn’t say anything, but seemed very interested. In fact, we had both constructed what would later be called a paraglider.

‘The Air Force had organised a demonstration day for the different projects in California. It was there that the glide ratio of 4.2 of my wing was officially measured.’

But a week after the demonstration, NASA HQ totally abandoned the idea of using parachutes. ‘They change their minds sometimes,’ David said with a rye smile. ‘Now, thirty years on, NASA has returned to the use of parachutes.’

The most recent, the X34 or “space life boat”, designed for recovering the space shuttle crews, is 30 metres across. The same size as Dave Barish’s design from 1966!

‘When the contract was terminated I just gave up,’ recalls David. ‘As far as parachutes are concerned I have never thought that I designed anything which was really much better than those of Jalbert or Snyder.

‘There were already 30 or 40 companies and as many legal fights. My whole professional career has been rooted in subsonic and supersonic aerodynamics.

‘In the science of low speed flight, there has been little innovation in the last 100 years. Most of what we need to know today has already been written in the books of Ludwig Prandtl, of the German school of aerodynamics.

‘Slope soaring was a hobby. In order to develop it I would have had to dedicate myself to it full-time. I had other inventions which I didn’t want to neglect.’

PARAMOTORS TOO

Closed cells, the profile, trim tabs, spinnaker fabric, flaps, 8 m lines, high aspect ratios, launch techniques, tree landings, the paramotor –

it all existed as long ago as the ’60s! But the explosion in popularity of the sport wouldn’t happen for another 20 years.

During the 1980s David Barish manufactured another paraglider with semi-closed cells, and then a hang glider for his son. Then, one summer’s day in 1993, whilst driving near the site of Ellensville just outside New York David spotted 30 paragliders in the air, and suddenly realised that slope soaring had grown into a huge sport. His interest was rekindled.

During a skiing trip to Europe he noticed how popular paragliding had become at resorts like Gstaad, Switzerland. ‘I was impressed by the number of companies selling equipment,’ he says. ‘Technically, I noticed the Airwave gliders with their diagonal cells.’

The following year he visited St Hilaire in France, where the number of wings laid out on the carpet finally convinced him of the sport’s size. At over 70 years of age, he returned to the drawing board and his sewing machine.

‘I did it to satisfy my intellectual curiosity. I looked at every aspect of current design to maximize performance, starting with a completely closed cell glider, and then adding a 30 degree sweep- but that didn’t work out!’

And in the last two years, David has even started to fly again! When he explains that he only flies himself because he ‘ran out of test pilots’, you may think he’s joking, but David did actually lose one of his best friends when his aircraft hit a mountain during foggy conditions.

An exciting clip from a video shot by Johanna during the summer of 1999 shows him taking off and flying at 100 m above the ground in turbulent conditions. The wing is an incredible prototype, very flat and with an aspect ratio of 8.

He reports: ‘Higher aspect ratio is one way to increase performance. I would not say it’s the easy way. But it is obvious that the result is a rather sensitive machine.’

Always discrete, David Barish has never promoted his discoveries. Philippe Renaudin, the Sup’Air importer for the USA, had met him many times with his wing and “home-made” harness, before learning that this amazing old gentleman had invented paragliding 35 years ago. And paramotoring too. And he still has things to teach us.

When Phillipe told him that his paramotor mysteriously climbs less well when facing into wind, David replied straight away that it was to be expected, because the angle of the propeller has been designed for a single pitch angle. The same problem existed for small propeller aircraft during the thirties, and was resolved by variable pitch propellers.

David has a daughter from his first marriage. When Johanna met David she warned Johanna straightaway, ‘My father does a lot of mad things, you don’t have to follow him!’

Thousands of paraglider pilots, without knowing it, have followed David Barish in their quest to fly like a bird. And it’s Johanna again who has the last word on her many years living with David: ‘We laughed a lot!’ One of the secrets of life.

But the story cannot be closed here. It is David himself who says, ‘I wouldn’t be surprised if one day someone finds a Russian or a Japanese engineer who did the same thing before I did!’

DAVID BARISH AT THE ST HILAIRE FESTIVAL

Guest of honour and president of the jury of the film festival, David Barish delighted everybody he met with his modesty, his kindness and his limitless curiosity.

He plunged into many passionate discussions with Gin Seok Song (Gin Gliders), Xavier Demoury (Nervures) and Jean-Louis Darlet (The Cage).

When flying tandem with Sandie he immediately asked to fly it himself and was eager to fly again the following day and play with some thermals.

Sandie said: ‘I was very flattered to fly with him. He flew the tandem until the last turn of our approach. On the drive back back up again we talked about skiing in Chamonix, where I am from. One day he got lost in the fog skiing the Vallée Blanche!’

Ever available, he gave interviews and press conferences, and had even brought his high aspect ratio prototype for a few inflations and to ask the opinion of other manufacturers.

Xavier Demoury knew the pedigree of David Barish and his Sailwing: ‘I didn’t think it could fly. It seemed crazy. But David, he made it fly 20 years in advance of everybody else.

‘The long lines, ripstop material, the deformation of the material under the pressure between interior and exterior; his work enabled us to arrive to where we are today.

‘He is a true inventor. As for us, we are only improvers! When I see him, I tell myself that I still have 30 good years ahead of me. It’s reassuring!’

David Barish died December 2009 aged 88. His obituary in the New York Times is here.

• Got news? Send it to us at news@xccontent.local. Fair use applies to this article: if you reproduce it online, please credit correctly and link to xcmag.com or the original article. No reproduction in print. Copyright remains with Cross Country magazine. Thanks!

Subscribe to the world’s favourite hang gliding and paragliding magazine