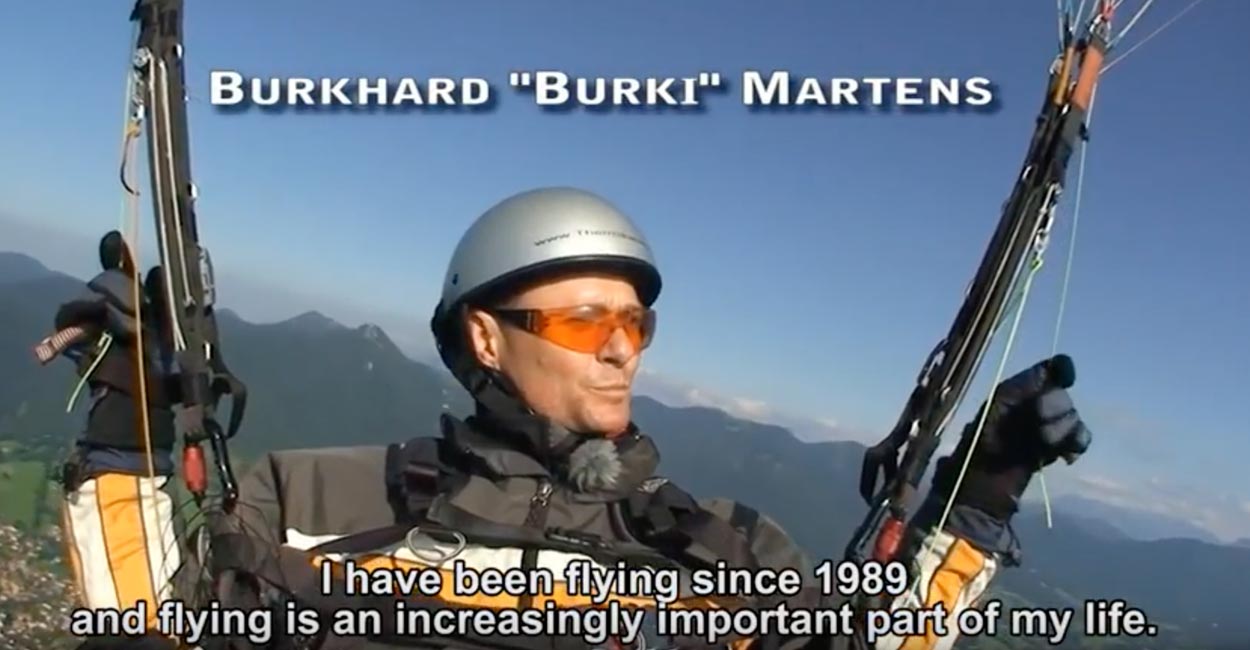

An extract from Thermal Flying by Burkhard Martens, the bible for paragliding and hang gliding pilots

Visualising thermals

Sadly, air is invisible, cold as well as warm. So to get the most of the conditions we need to be able to build a mental picture of the thermal we’re circling in, to visualise it in our minds.

Some thermals are very large and may even be kilometres long, for example under long cloud streets. Others are small, narrow, or made up of several cores, each showing significantly different climb rates. In the next pages we’ll be showing a number of different thermal structures, to help you in your own visualisation process.

The vortex structure of thermals

Smoke rings blown by cigarette smokers give a good visual clue as to the structure of thermal vortices. We know from experience that the thermal is several times stronger in its core than closer to the edges. Why is that so?

To explain it, the vortex-structure theory was developed. The accuracy of the theory can be affirmed often enough through observations: when the thermal rises the friction against the surrounding air slows it down along the edges. This sets off a rotating movement from the inside out, like when we turn out a sock. These vortices may be observed both in thermal bubbles and in thermal columns.

Let’s look at the significance of this vortex ring structure for the pilots A to E:

Pilot A is in the core and climbing twice as fast as pilot B, who is at the apex of the climb. Once pilot A catches up with B they will continue with identical climb rates.

Pilot B is flying against the head wind caused by the vortex ring. If he’s carrying a GPS he may notice that his ground speed is lower than it was shortly before. If he flies over the centre of the core he’ll suddenly have a tail wind combined with lower climb rates. It is possible to sense the acceleration when moving over the core and into the tail wind, and the pilot should turn immediately to stay in the core and maximise his climb.

The core of the vortex ring is rather turbulent and the pilot must continuously respond to the pitching of his wing and carry out adjustments to remain in the strongest lift.

Pilot C is still above the thermal. Only when he has sunk down to the level, and it has climbed up to meet him, may he commence thermalling and gaining altitude.

Pilot D has fallen out of the side of the thermal and is heading away. Provided he’s carrying a GPS he may notice his ground speed picking up whilst his sink rate is also increasing.

Pilot E is approaching the thermal low down. He has a tail wind and already should see reduced sinking – he’s practically being sucked into the thermal.

The example above shows how important it is for each of us to always try to build up a mental picture of the thermal we’re in: to visualise it. Only by doing so may we understand what is going on all the time in relation to which part of the thermal we’re in, and make the most of it. This also allows us to re-enter the core quicker in case we loose it.

Tip: If I’m flying straight and suddenly feel an increased drift towards one side, maybe even combined with reduced sinking, I always follow the drift immediately. Chances are I’ll fly right into a thermal, just like pilot E is about to do.

Experience

I had the most amazing experience surfing a vortex ring in a very strong thermal once. I was going up at 9+ m/s on a no-wind day, and suddenly realised by looking at my GPS that my forward speed had gone to zero! At the time I was thinking hard about where that very strong headwind had suddenly come from, but today I realise that I was simply at the apex of the vortex ring, pointing right into the outflowing air (see pilot B).

I eventually made 1,500 m vertically in very little time, flying straight and remaining practically on the spot! Impressive!

Let’s imagine two pilots trying to exploit the lower end of a thermal bubble rising as a vortex structure; one is 50 m lower and soon gets left behind by the bubble, which due to his sinking through the surrounding air mass is always rising faster than him. But the other pilot who is 50 m higher makes it into the centre of the vortex ring where the rising air is accelerated by the vortex structure.

In spite of the thermal bubble rising with 1 m/s the centre is producing climb rates of 2 m/s which just balances out the sinking of the paraglider. If it wasn’t for this effect, and assuming a min sink of -1m/s, the upper pilot would sink out of the bottom of the thermal bubble in 50 seconds (he was

A thermal bubble rising. The lower pilot loses it early on, and searches in vain for the now much higher thermal. The upper pilot just makes it into the centre of the vortex ring, where he manages to remain. The lower pilot can only watch as his buddy becomes smaller and smaller.

Within the thermal are several ’hotspots’ where the lift may be even better

TIP: Vortex rings are commomplace among isolated thermals with narrow cores. When the thermals grow large, as they do under cloud streets etc. the structure is rare.

A cloud showing classic vortex shape. By looking at such clouds we may learn a lot about the structure of the invisible thermals.