Storm outflow can travel unimpeded for miles downwind. Meteorologist Honza Rejmanek talks about the effects of storm clouds that you can’t see.

From ground-school days onward, soaring pilots learn to respect thunderstorms. They are to be respected because the updraughts and downdraughts stretching through the depth of the troposphere can be intense, to say the least. Strong updraughts have whisked pilots to above 10,000m like leaves in a vacuum cleaner.

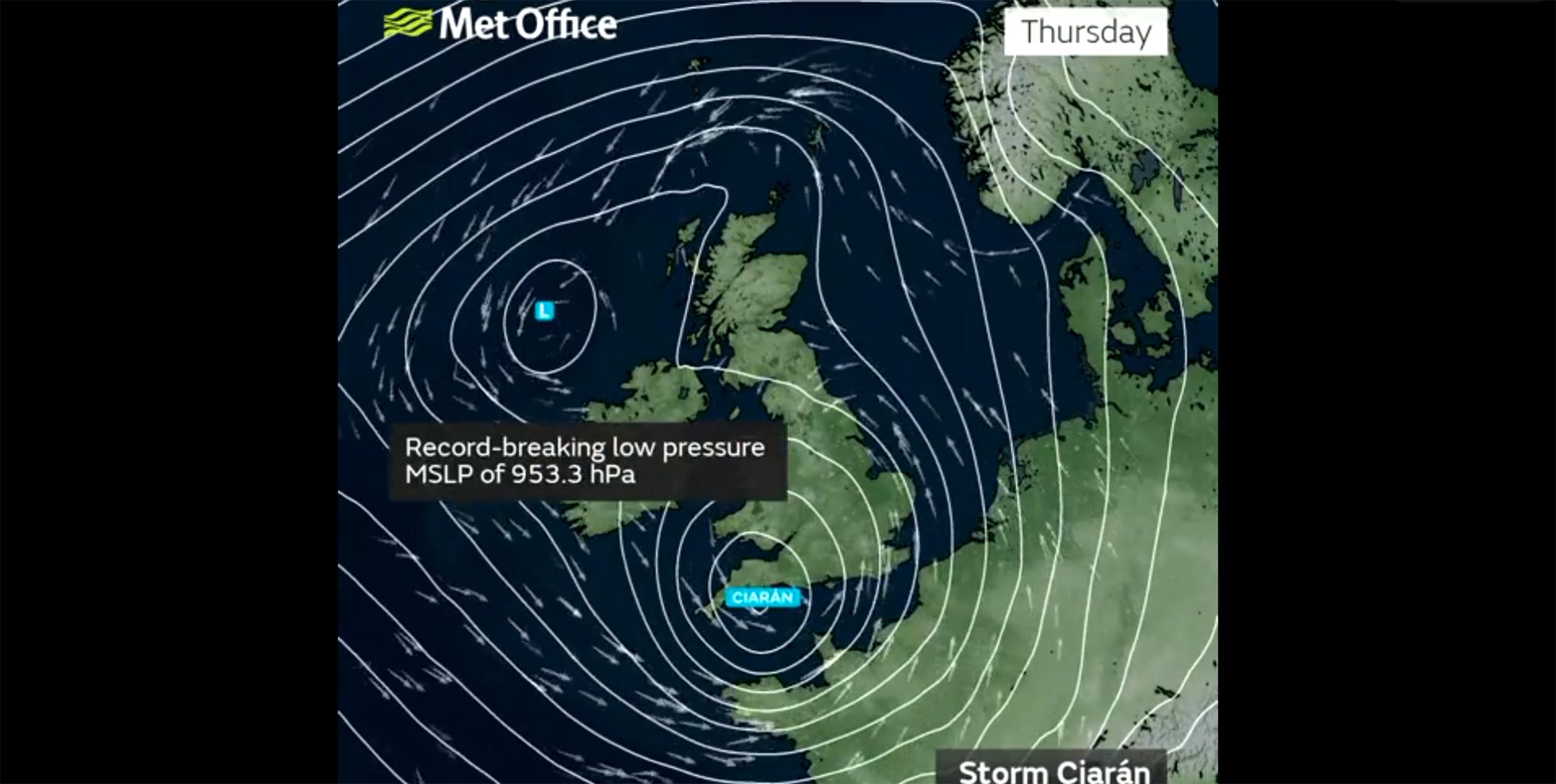

If this happens it is usually because several warning signs were not respected or a storm, or a line of storms, moved in extremely quickly. Sometimes storms can move in at over 30 knots (55km/h) and the sky can change very quickly. The other danger from thunderstorms is the extreme downdraughts that spill outward as a gust front. This is best thought of as the broken dam or avalanche of the sky.

Caught by the outflow

A growing thunderstorm with its strong updraughts is easier to spot than the outflow and associated gust front. This is especially true when the gust front is produced by a storm that is far away and when visibility is limited, or view of the storm is blocked by terrain. Therefore, more pilots get caught off guard by this outflow feature of a thunderstorm.

On 4 August at Hat Creek Rim in Northern California a dozen pilots were airborne enjoying sunset flying when a gust front arrived from storms that were not visible on the horizon. This is a west-facing flying site known best for its late-afternoon glass-off conditions. More advanced pilots had been airborne for quite some time. Other pilots had chosen to wait for the wind to drop. The last pilot launched at 8.14pm, just two minutes before the arrival of the gust front, believing it would be a short sled ride to the landing zone.

A pilot who was airborne and well above launch described what happened as the gust front arrived: “It was very interesting to see how the gust front affected pilots at different altitudes. Those below launch at 8.16pm were very quickly slammed with strong north wind and increasing sink as the gust front arrived.

“Those who were well above launch first began to experience strong and increasing widespread lift, initially with only modest change in wind speed and direction. As we headed towards the LZs and employed descent techniques, we sank into the gust front, hit a wall of north wind and rapidly increasing sink.

“Before I sank into the gust front, I was about 1km south of LZ2 and nearly 1,000m above. A glide of only 1:1 would have been sufficient. A minute later, I was going backwards and sinking fast.”

This pilot backed into a clearing in the trees and landed safely. One pilot landed in trees, and another fractured a vertebra. All others managed to land safely.

After the initial gust front arrived the strong wind blew for over an hour with only a short period where it momentarily decreased. When the wind finally stopped it was fairly sudden.

The fact that there were no storms in the immediate vicinity of the flying site means that this gust front arrived from afar. The fact that it blew so strongly and for over an hour indicates that it most likely originated from multiple cells possibly as far away as 100km north-northwest of Hat Creek Rim. Later examination of radar and satellite loops did indicate that there were strong thunderstorms to the north and east.

The gust front arrived as a north wind and continued to blow from that direction. Thus, it was the storms far to the north, close to the Oregon border, that were the most likely culprits.

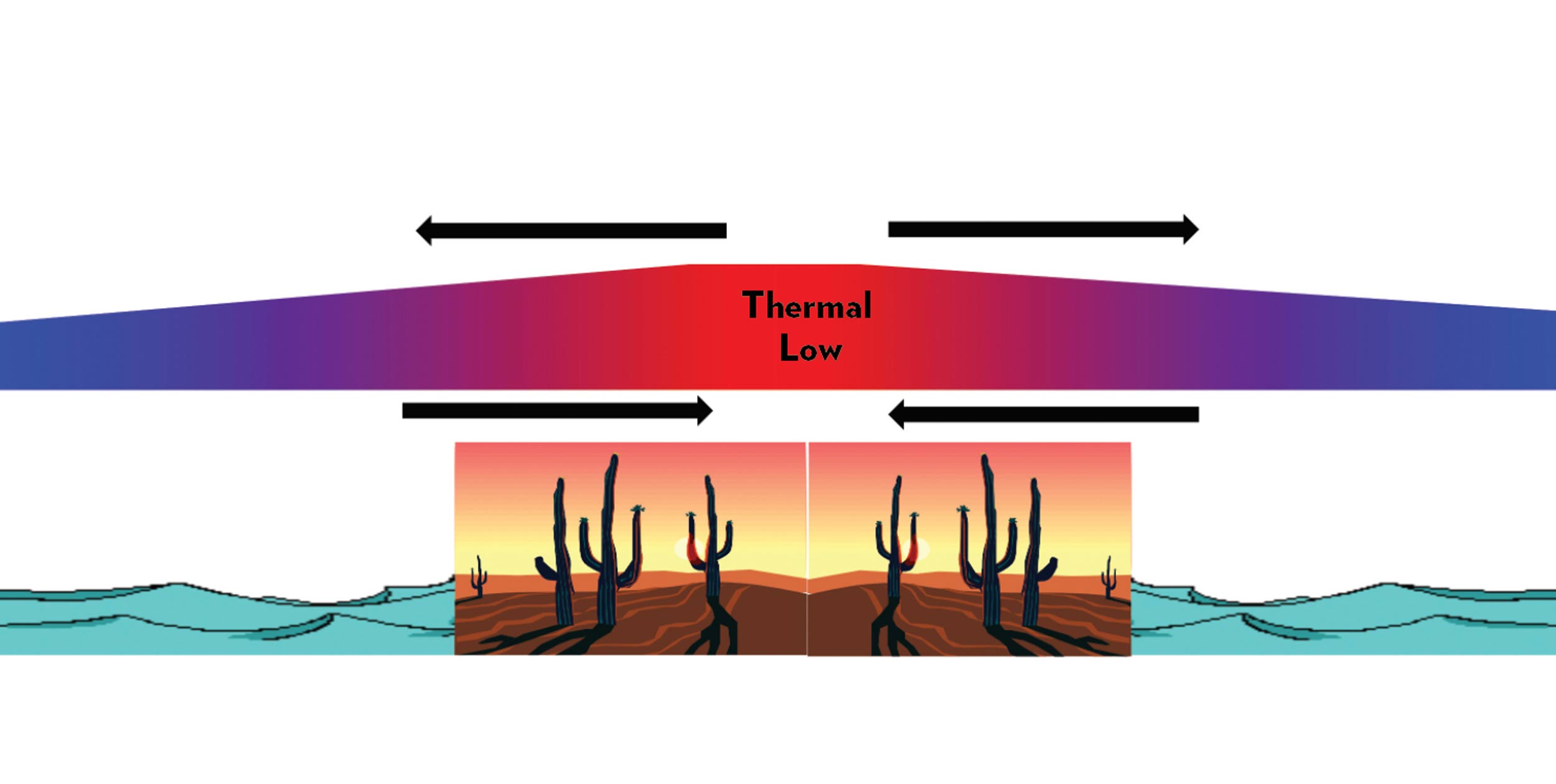

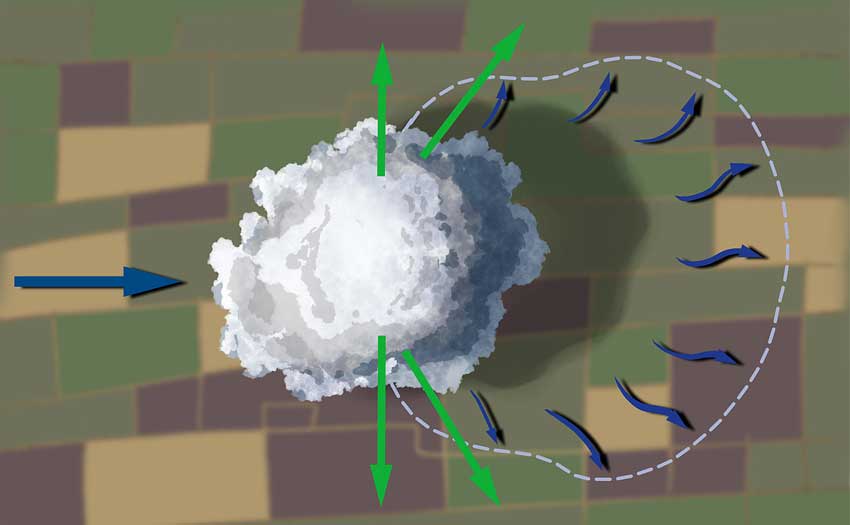

When cool air descends out of a storm cell it hits the ground and spreads out, flowing downwind. The edge of this outflow is the gust front, and in the flatlands it can travel for miles unimpeded. Illustration: Steve Ham

Haboobs and arc clouds

A gust front and associated outflow is a density current that is colder than its surroundings by a few degrees and behaves much like water would if a dam burst. In this analogy the volume of the reservoir is the size of the storm or series of storms.

Examination of the topography to the north-northwest of Hat Creek Rim shows that there are no prominent mountains to block a long cold outflow. If anything, there might be some channelling.

As a contrast, in the Alps gust fronts can spill violently down individual valleys but, given the steep convoluted terrain, it is nearly impossible to have a gust front arrive from 100km away. There is just too much terrain in the way.

In dusty desert regions dust storms called haboobs can travel over 100km. These are gust fronts from far away storms, but their arrival can be seen due to the fine dust they carry.

In very moist areas a gust front gives clues to its presence as an arc cloud or, if close to the storm, it is called a shelf cloud. At Hat Creek Rim it was too dry for an arc cloud yet not dusty enough for a haboob. Pilots did note the smell of rain just before the full force of the gust front was felt.

Nowcasting

These days we have tools in our pocket that we did not have 20 years ago. Even if no storm is visible in the immediate vicinity, it is worth checking the satellite loop and the radar loop on our phones. The tough call is deciding how far is far enough for an active storm. Too much caution might leave a pilot missing many great flights.

The optimal approach might be to evaluate storm strength from the intensity of radar echo and duration over a fixed location and then draw a line to your flying site. If there is no significant terrain to deflect a possible gust front, then it would be wise to keep an eye out on any real-time wind reports from stations in the far-off storm’s direction. Of course, some regions have no anemometers.

This type of nowcasting is not a perfect science. However, thanks to satellite and radar on our phones it can give us more of an idea of what is going on in real-time beyond our immediate horizon and help us make more informed fly/no-fly decisions.

Published in issue 244 (October 2023)